Today’s Des Moines Register features a long front-page story by Daniel Finney and Jeffrey Kummer on Storm Lake (Buena Vista County) as one of Iowa’s most diverse communities, and expected trends in the state’s demographics between now and 2020. I encourage you to click through and read the whole thing. After the jump I’ve enclosed a few excerpts and one graphic from the feature. Separate, shorter pieces examine diversity trends in the Des Moines metro area (Polk and Dallas counties), Webster County (including the Fort Dodge area), and Butler County (the least diverse in Iowa).

On Monday, Michael Barbaro of the New York Times examined Iowa’s population shift from rural to urban and suburban areas as “a potent but unpredictable undercurrent in a closely fought Senate race.” I’ve enclosed a few excerpts at the end of this post. Barbaro interviewed people northwest Iowa’s heavily white Pocahontas County, as well as in downtown Des Moines, the far western suburbs in Dallas County, and Denison (Crawford County), a town where almost half the residents are Latino.

I spent some time in Denison last fall and was impressed by the vibrant downtown, with more locally-owned shops and restaurants than I’ve seen in most Iowa towns of similar size. One resident told me that approximately 75 percent of students in Denison’s public schools are Latino. That has helped the area avoid the steep enrollment declines and school closures seen in Pocahontas, as Barbaro recounts, and in so many other communities.

Any relevant comments are welcome in this thread.

From the October 22 Des Moines Register feature by Daniel Finney and Jeffrey Kummer, Iowa to follow Storm Lake’s lead in diversity:

Buena Vista County has a Diversity Index rating of 49, which means that a person of any racial or ethnic background has about a 50-50 chance that the next person he or she meets will be someone of a different race. By 2060, Iowa as a whole is predicted to have a Diversity Index rating of 47.

It’s part of a phenomena happening across the country. Places far removed from traditional urban gateways are rapidly becoming some of the most diverse places in America.

In practical terms seen through daily life in Storm Lake, it means growth in the local economy and in school enrollments. Officials say it also has brought an understanding of a wide variety of people and cultures and one heck of an annual Fourth of July parade. […]

Storm Lake public schools are more than 80 percent non-white, with 18 languages spoken. The parochial schools are nearly 50 percent non-white. Iowa Central Community College, which teaches English to adults, helps residents who speak as many as 35 different native languages. […]

Public access signs in the community are often in two languages: English and Spanish. Police, paramedics and other public service agencies have bilingual officers and staff, useful to handle emergencies and to make daily life easier throughout the entire community. […]

While Iowa will be more diverse than it has ever been by 2060, it will still be among of the least diverse states in the nation. Iowa has ranked at the bottom 10 of states in diversity since 1960 and will continue to do so through 2060.

For example, Iowa’s predicted Diversity Index of 47 by 2060 is identical to that of Mississippi in 1980.

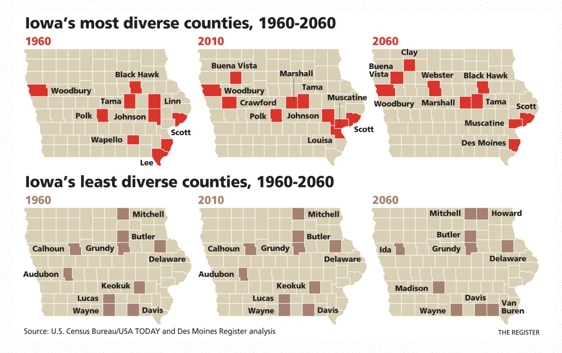

Des Moines Register graphic showing the ten most diverse and least diverse Iowa counties in 1960, 2010, and what’s projected for 2060.

From Michael Barbaro’s piece for the New York Times on October 20, With Farms Fading and Urban Might Rising, Power Shifts in Iowa:

The state’s once ubiquitous farms are supporting fewer workers, the towns built around them are hemorrhaging younger residents, and a way of life eroding for decades is approaching a denouement. Farm fields are yielding to the new headquarters of banks, insurance companies and health care providers, whose rapid expansion is luring waves of Iowans to cities and suburbs, and contributing to the state’s enviable 4.5 percent unemployment rate.

In jarring and telling tableaus, new housing subdivisions, with names like Stone Prairie and Walnut Creek Estates, are rising up in the Republican precincts west of Des Moines and downtown office buildings in the Democratic-leaning state capital are being remade into loft-style apartments. When researchers at Iowa State University studied population trends between 2000 and 2013, they found that the state’s metropolitan areas had grown by 13.3 percent. The population of communities outside those urban areas fell by 3.6 percent, a gap that far outstrips the rest of the Midwest.

Those changes have turned Iowa’s older, Republican precincts even redder and its younger, Democratic districts even bluer, while giving rise to suburbs whose politics can be harder to categorize – a mixture of millennial generation religious conservatives, baby boomer libertarians and Generation X liberals. […]

Laurens, which flirted with a population of 1,800 in the 1960s, was down to 1,476 in 2000, then 1,258 in 2010. The story is similar across Iowa: Once-vibrant communities have been shattered in two waves, first by the farm crisis of the 1980s, then by technological improvements that encouraged far bigger farms and required far fewer farmers.

As of 2011, Pocahontas’s farming industry employed 764 people, about half as many as in 1980.

Those who stay are largely Republican. Susie Mayou, a 55-year-old conservative, described herself as heartsick that Democrats had carried Iowa in six of the last seven presidential elections. “If Iowa gave power based on land ownership, the state would swing 180 degrees,” she said. “The city people push the agenda.”

I had to laugh at that last comment. If the “city people” were really pushing the agenda in Iowa, we wouldn’t have some of the country’s dirtiest water.