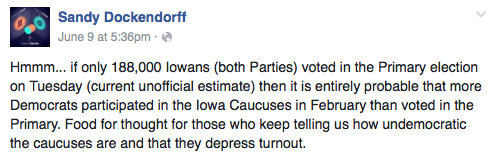

A member of the Iowa Democratic Party’s Caucus Review Committee posted this Facebook status update on June 9:

Where to begin?

Forget “entirely probable”: the number of Iowans who cast ballots in last Tuesday’s Democratic primary (96,934 according to the latest unofficial results) was substantially lower than the number who attended the February 1 precinct caucuses (171,109 according to the Iowa Democratic Party). That’s a nearly 45 percent drop in participation.

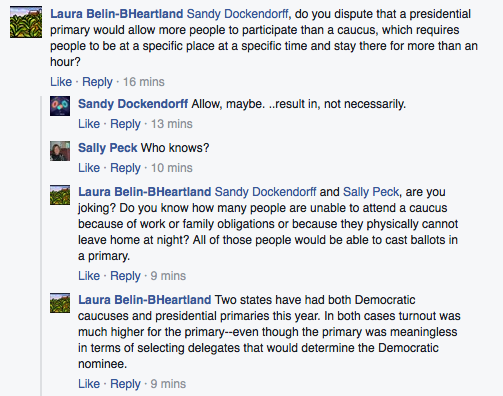

The low turnout for the June 7 primary suggested a relative lack of interest in who would become the Democratic nominees for U.S. Senate or U.S. House in Iowa’s first and third districts. But does the level of participation in the primary indicate, as Dockendorff implied, that people like me are wrong when we say the Iowa caucus system excludes thousands of politically-engaged Democrats? I raised the question further down that Facebook thread.

I thought it was generally accepted by now that caucuses exclude more people than primaries do. Anyone who has volunteered for a presidential campaign in Iowa (a group presumably including Dockendorff) can tell stories about people they identified as supporters who were unable to attend the caucuses for various reasons. But Dockendorff insisted later in that online conversation, “Clearly, allowing access does not translate into an automatic increase in participation.”

Let’s leave anecdotes about frustrated non-caucus-goers aside and look what some of this year’s Democratic presidential contests can tell us about whether primaries inherently lead to greater turnout.

DO PRIMARIES PRODUCE HIGHER TURNOUT? IOWA VS. CONNECTICUT

I chose the Connecticut primary for comparison because Connecticut’s voter universe is close to Iowa’s in size. As of October 2015 (the latest figures available on the Secretary of State’s website), Connecticut had 2,129,379 total registered voters, of whom 1,923,103 were active registered voters.

As of February 1, 2016, Iowa had 2,095,639 registered voters, of whom 1,937,317 were active. Those totals don’t include the thousands who registered to vote for the first time at their precinct caucus site.

In reality, the pool of potential Iowa Democratic caucus-goers was much larger than the pool of potential Connecticut primary voters. Iowa Democratic and Republican caucuses are “semi-open”; anyone can change party registration, if desired, immediately before the caucus in order to participate. Assuming Republicans would want to attend a GOP precinct caucus, at least 1.3 million Iowans theoretically could have attended a Democratic caucus (586,835 active registered Democrats plus 727,112 no-party voters).

In contrast, Connecticut held a “closed” primary, meaning only registered Democrats (not “unaffiliated” voters or Republicans) were able to cast ballots for either Hillary Clinton or Bernie Sanders on April 26. So assuming the number of registrants didn’t change much between October 2015 and this spring, somewhere between 700,000 and 800,000 Connecticut voters were eligible to participate in the Democratic primary.

Now consider campaign organization and voter mobilization.

The Clinton campaign had at least 26 offices open in Iowa by the end of 2015 and probably more than 100 paid staffers here, compared to a much smaller staff working in its five Connecticut field offices.

Sanders had at least 23 campaign offices open in Iowa and scores of field organizers scouring our state, compared to one campaign office and a handful of staffers in Connecticut.

Even Martin O’Malley’s campaign had three Iowa field offices and more than a dozen people paid to identify and turn out O’Malley supporters for our caucuses.

Clinton, Sanders, and O’Malley visited Iowa dozens of times, each spending more than 40 days campaigning in the state.

As of a few days before Connecticut’s primary, Clinton had visited that state once, Sanders not at all. Both campaigns had held some Connecticut events headlined by other supporters. By comparison, Sanders spoke to more than 50,000 people at his numerous Iowa rallies in 2015 and early 2016.

Add in intangible factors: Iowa went first, when the Democratic nomination was anyone’s for the taking. Hundreds of media organizations sent reporters to Iowa to cover the final days of the caucus campaign. By the time Connecticut voters had a chance to weigh in, 36 other states had already held primaries or caucuses, and Clinton had built up a big pledged delegate lead over Sanders.

If caucuses present no special barriers to participation compared to primaries, we would expect to see much higher turnout in Iowa than in Connecticut. Instead, 171,109 caucus-goers attended Democratic precinct gatherings on February 1. More than 322,000 Connecticut voters cast ballots in the April 26 primary: 170,080 for Clinton, 152,415 for Sanders.

DO PRIMARIES PRODUCE HIGHER TURNOUT? NEBRASKA AND WASHINGTON

Two states held caucuses to select pledged delegates for the Democratic presidential candidates, then held primaries later in the spring. The Clinton and Sanders campaigns invested in field operations before the Nebraska and Washington caucuses but did little GOTV in either state before the “beauty contest” primaries.

About 33,460 Democrats participated in the Nebraska caucuses on March 5. But more than 80,370 voters cast ballots for Clinton or Sanders in Nebraska’s non-binding primary on May 10, despite the lack of voter mobilization efforts by either presidential campaign.

Same story in Washington: about 800,000 people cast ballots in the meaningless Democratic primary on May 24. Turnout for the March 26 caucuses, which elected delegates for either Clinton or Sanders, was estimated at around 230,000.

I am not saying Iowa should abandon our caucuses for a primary. I recognize that starting the presidential nominating process is valuable, and New Hampshire law stipulates that their state must hold the first primary.

But we do need to make our caucuses more inclusive and more representative, especially since before long, Democratic National Committee leaders may try to change party rules to ban caucuses for the purposes of presidential delegate selection.

It concerns me that a member of the committee selected to improve the Iowa caucuses seized on low primary turnout to suggest that caucuses don’t really exclude voters or distort their preferences. Last week’s voting by Democrats doesn’t imply that Iowa caucus turnout was as high as it could have been with fewer barriers to participation.

If I felt Dockendorff were an isolated voice in influential Iowa Democratic circles, I wouldn’t have paid any attention to her Facebook post. But quite a few members of the caucus review committee have publicly stated that the caucus system mostly works well and needs no major changes.

The first step in solving a problem is acknowledging the problem exists.

UPDATE: I should have mentioned that Dockendorff serves on the Iowa Democratic Party’s State Central Committee and is the current Rules Committee chair.

LATE UPDATE: Jim Kessler, senior vice president for policy at the “centrist” think tank Third Way, published an op-ed in the June 21 Washington Post that Iowa Democratic leaders should read: “Want to help end voter suppression? Junk the caucuses.” Kessler isn’t the first and won’t be the last to cite obstacles to participating in caucuses and the disparate turnout from Washington’s caucuses and primary. But this damning statistic from his column was news to me:

If voter suppression is truly a Democratic concern, consider that fewer people participated in the 17 caucus races in the recently completed Democratic nominating contest than those who turned out for the Wisconsin primary alone. These 17 caucus races with minuscule turnout selected 528 earned delegates to the convention. Wisconsin, where roughly the same number of voters cast a ballot, chose just 86 delegates. If that seems undemocratic, it is.

6 Comments

I'd comment, but...

…as someone NOT picked for the Caucus Review Committee, it’s clear my opinion has no value

jdeeth Mon 13 Jun 4:39 PM

First In Nation...

What affect would changing the Iowa Caucus have on it’s “first in the nation” role, as the complexity of the process attributes to the argument to be first in the nation?

Secondly, if Iowa lost it’s first in the nation status, would the decrease in interest from candidates and media lead to decreased turn out?

If so, would the decreased turn out from losing the national spotlight be less than what is already lost in having a caucus?

There is no definite answer to these but it’s an interesting cause/effect rabbit hole to keep in mind as changing too much of the caucus runs risk of losing the national spotlight that drives a lot of individuals to the polls. Not to mention the loss in money to the state economy by not having campaigns spend their time and budgets in the state leading up to the first in the nation caucus.

That being said, as a shift worker, I think an adjustment to making the caucus have a less restrictive timeline would be a major improvement to get more people included.

zbert Tue 14 Jun 8:58 AM

Dave Swenson has analyzed

presidential campaign spending and found that much less money flows into the Iowa economy than you would think.

We might have lower turnout if we are no longer first in the nation. But it’s striking to me that after months of candidates, campaign staffers, and volunteers working this state very hard, our turnout for the caucuses was only a little more than half the level of turnout in Connecticut, which held the 37th nominating contest.

desmoinesdem Tue 14 Jun 10:03 AM

Good Point...

Good point and thank you for the reply. And, on second thought, there was only a loss of 44% in participants. That is with races getting so little attention that the night before the primary, the Democratic Senate Debate from May 26th on IPTV only had 203 views… which would demonstrate that Iowans care enough about their politics to keep strong attendance despite the attention.

zbert Tue 14 Jun 8:00 PM

People with disabilities and caucuses

Bleeding Heartland, I have people with disabilities in my family who cannot caucus due to their disability. Thank you for advocating for the disability community. Caucuses are very ableist.

farmgirl Wed 15 Jun 9:31 PM

they really are

I was not aware of this until my first experience doing GOTV as a precinct captain before the 2003 caucuses. Even if every precinct caucus were held in an ADA-compliant facility, many people would be unable to attend.

desmoinesdem Sat 18 Jun 9:48 PM