Governor Kim Reynolds found a way to make a bad situation worse.

In the past month, Iowa’s coronavirus deaths have accelerated, while hospitalizations have nearly doubled, far surpassing the previous peak in early May.

Despite numerous warnings from experts that Iowa is on a dangerous path, Reynolds refuses to take any additional steps to slow community transmission of the virus. Instead, she is sticking with the “trust Iowans to do the right thing” playbook, confident that hospitals will be able to handle the influx of COVID-19 patients.

The numbers speak for themselves.

IOWANS DYING AT A FASTER RATE

COVID-19 remains on track to kill more Iowans in 2020 than any cause of death other than heart disease and cancer. With an official tally of 1,617 total fatalities on the morning of October 23, coronavirus has eclipsed the fourth, fifth, and sixth leading causes of death in Iowa in 2017 (Alzheimer’s disease, accidents, and strokes, respectively).

The state’s count understates the real death toll, but by how much is unclear. Coronavirus.iowa.gov lists only two deaths for Van Buren County in southeast Iowa, where local public health has been reporting three deaths since August 24 and has reported five deaths since October 12. Amy McCoy of the Iowa Department of Public Health has not replied to Bleeding Heartland’s many inquiries about this discrepancy, nor has she or anyone else explained the methodology state officials use to count COVID-19 deaths.

Despite the shortcomings in the data, I used the state website’s numbers to create this graph. The IDPH records fatalities by the date on the death certificate, which reflects when the patient passed away, not when the information reached the state. It often takes several days and may take up to two weeks for deaths to be added to the dashboard. The orange line represents the seven-day moving average.

Another way to look at this trend is to compare the pace at which Iowans are dying from this virus. Following the state’s first reported COVID-19 death on March 24, 28 days passed before the death toll reached 100 on April 21. Then, state data show, it took:

Iowa will lose more than 300 people to COVID-19 in October alone, and flu season is just getting started. Experts have warned for months that colder temperatures and lower humidity could accelerate virus transmission, as is the case for other coronaviruses.

Even more Iowa families will lose loved ones in November, judging by recent trends in hospitalizations.

HOSPITALIZATIONS RISING SHARPLY

Since mid-September, hospitalizations are up by nearly 100 percent statewide and have more than doubled in the region that covers 20 counties in northwest Iowa. The 536 Iowans hospitalized for COVID-19 as of the morning of October 23 is the highest number recorded yet, as is the fourteen-day rolling total (973 hospitalizations). On October 6, the state surpassed the daily peak from the first wave (417 hospitalizations on May 6).

Sources from around Iowa have told me they question the accuracy of the hospitalization figures IDPH publishes. It’s a reasonable supposition, given the longstanding problems with the state’s testing data, inconsistent case numbers for various counties, and county-level positivity rates that rarely match what watchdogs calculate.

That said, I have not been able to confirm flaws in the hospitalization figures. (Please contact me confidentially if you know otherwise.) For lack of a better dataset, I created the next two graphs from the “RMCC” page of coronavirus.iowa.gov.

Note the trend. Hospitalizations reached a low point in late June, then rose slowly for the rest of the summer, dipped a bit after Labor Day, and have taken off during the past month. UPDATE: Iowa reached a new high of 545 COVID-19 hospitalizations on October 23, and the number rose to 561 on October 25. LATER UPDATE: Hospitalizations reached 596 by the evening of October 27.

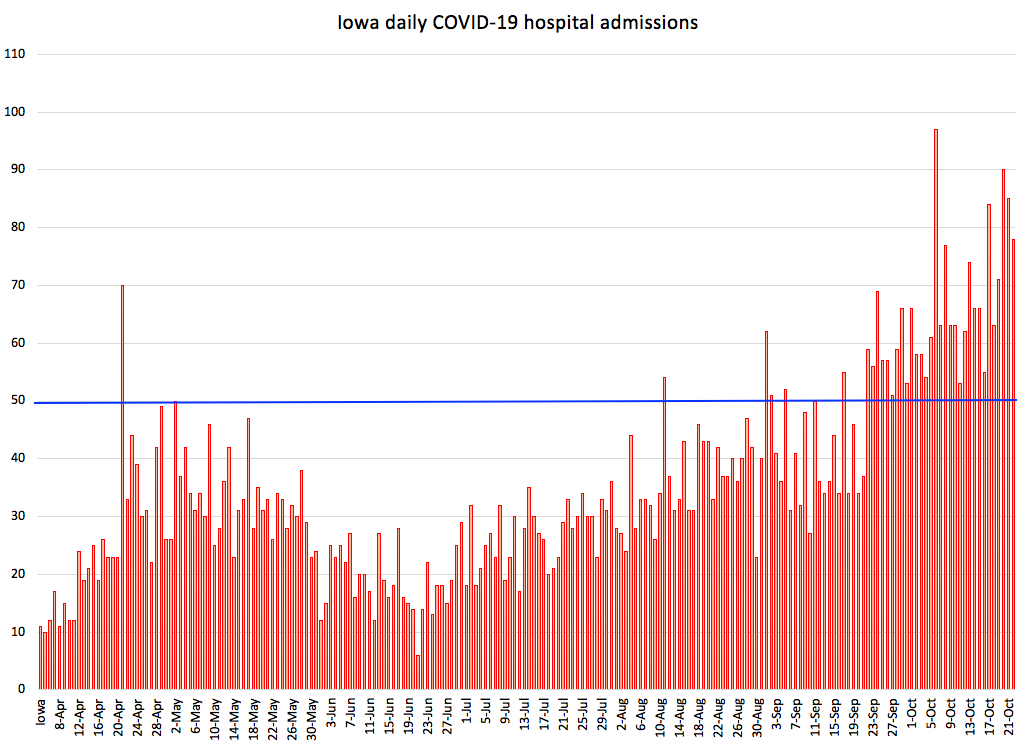

The daily hospital admission numbers are on a steep upward curve as well. The blue horizontal line represents 50 new admissions for COVID-19. Before September 22, Iowa reached that level only seven times. Since September 22, new hospital admissions have exceeded 50 every single day. UPDATE: The state reported 101 hospital admissions on October 23 (a new record) and 85 admissions the following day.

New reported COVID-19 cases often top 1,000 in a day, adding plenty of fuel to the fire.

Since Bleeding Heartland last covered this topic four weeks ago, Iowa’s number of daily new cases per 100,000 population has increased from 28.0 to 34.1, according to the COVID Act Now project. We have only 7 percent as many contact tracers as we would need to keep up with this caseload.

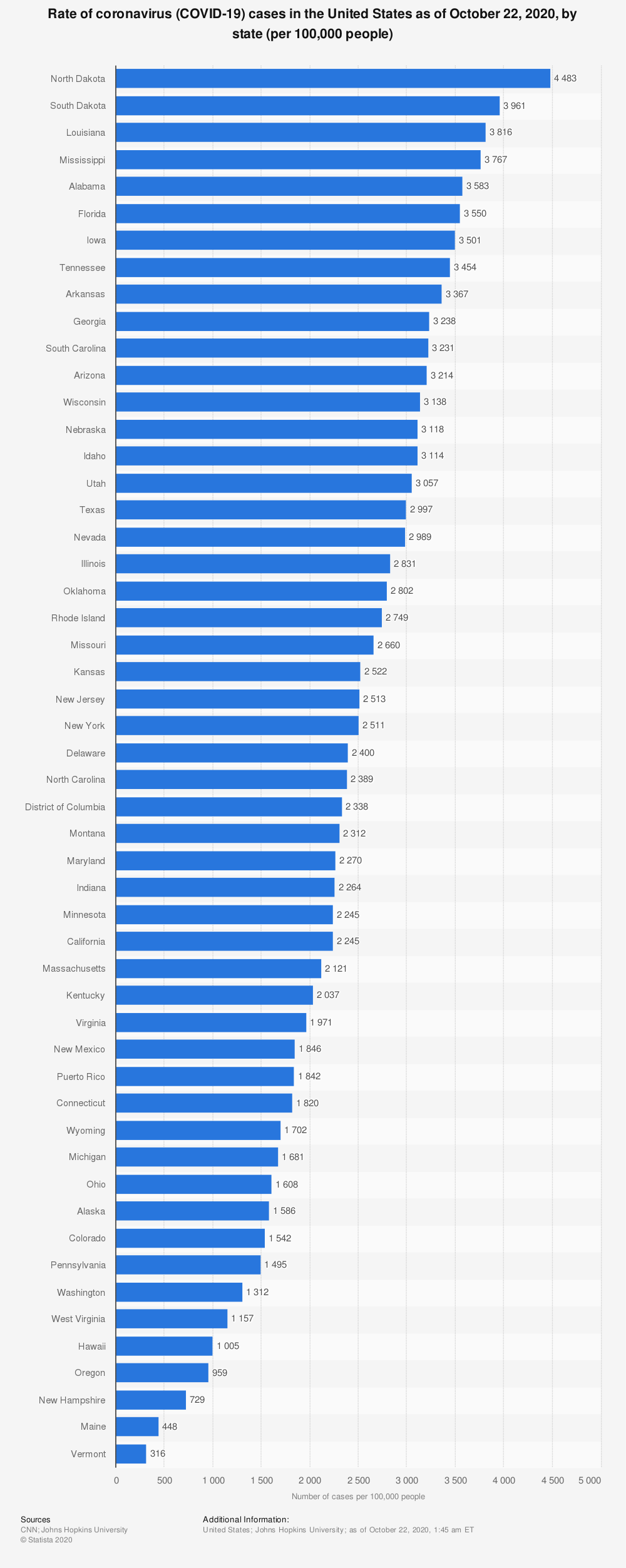

Also during the last four weeks, Iowa has moved up from ninth place to seventh on the list of most COVID-19 cases per capita. We would rank even higher, but North Dakota and South Dakota leapfrogged us and now have the worst outbreaks in the country. This graphic comes from Statista.

It didn’t have to be this way. With our relatively low population density, we should have been able to get this virus under control.

WARNINGS IGNORED

For months, experts have urged Reynolds and IDPH leaders to act more aggressively to slow the spread of COVID-19. Bleeding Heartland previously reported on recommendations from a team of University of Iowa epidemiologists and researchers in the College of Public Health. They told the IDPH in early May that their analysis showed “COVID-19 will continue to spread in Iowa, likely at an increasing rate.” Later the same month, they recommended policies to promote universal use of face shields in public, which “could rapidly and dramatically reduce the number of infections across the state, allowing society to reopen safely while continuing to decrease the number of new infections.”

Reynolds opted to lift almost all restrictions on businesses and gatherings in May and June, without any strategy to increase the use of face coverings. She and IDPH leaders rolled out a “Step Up, Mask Up” public relations campaign in mid-July, but the governor didn’t even stick to the program herself at political gatherings. (She still doesn’t wear a mask consistently around others.)

Not only has the governor spurned advice from the University of Iowa’s top faculty with expertise in infectious disease control, she has also ignored the Trump administration’s suggestions.

The White House Coronavirus Task Force has regularly provided reports to leaders in all 50 states to discuss the latest trends in virus transmission and recommendations for addressing problem areas. Over the past three months, those experts could not have been more clear about what Iowa should be doing to reverse the trends.

The July 26 report included the following advice: “In localities with 7-day average test positivity greater than 10%, close bars and gyms, require strict social distancing in restaurants (restrict indoor dining and promote outdoor dining), and restrict gatherings to fewer than 10 people.”

The August 9 report contained stronger wording. Task force leader Dr. Deborah Birx discussed these recommendations in person with State Medical Director Dr. Caitlin Pedati.

• Very slow drop in transmission (as measured by case rates and testing positivity) could be accelerated by intensifying restrictions in all counties and cities with case rates over 100 per 100,000 population.

• Mandate cloth face coverings outside of the home, especially in indoor settings in all yellow and red zone counties and metro areas.

• Close indoor bars and gyms, limit indoor dining and restrict gatherings as described below for yellow and red zone counties and metro areas.

None of those things happened, of course. The August 23 report was even more direct.

• With the continued geographic expansion of COVID-19 spread, a mask mandate needs to be implemented statewide (in counties with 20 or more cases) to decrease community transmission. […]

• Bars must be closed, and indoor dining must be restricted to 50% capacity in yellow and 25% capacity in red zone counties and metro areas. Expand outdoor dining options.

• In red zones, limit the size of social gatherings to 10 or fewer people; in yellow zones, limit social gatherings to 25 or fewer people.

On August 27, Reynolds again rejected a mask mandate. She ordered bars closed in six counties containing large metro areas or college towns, citing large numbers of new infections among young adults. Notably, the governor didn’t close bars in rural counties with rising case counts or high positivity rates. Nor did she limit large gatherings anywhere.

White House experts weren’t ready to give up on broader mitigation efforts. From the August 30 report:

• Community transmission continues to be high in rural and urban counties across Iowa, with increasing transmission in the major university towns. Mask mandates across the state must be in place to decrease transmission.

• Bars must be closed, and indoor dining must be restricted to 50% of normal capacity in yellow zone and 25% of normal capacity in red zone counties and metro areas. Expand outdoor dining options.

• Community spread must decrease to protect vulnerable populations in nursing homes.

The September 6 version tried again to make the case for more enforcement of social distancing and face coverings.

• Require masks in metro areas and counties with COVID-19 cases among students or teachers in K-12 schools. […]

• Bars must be closed, and indoor dining must be restricted to 50% of normal capacity in yellow zone and 25% of normal capacity in red zone counties and metro areas. Expand outdoor dining options.

Reynolds still wasn’t interested in further restrictions. At her September 10 news conference, she again asserted Iowa could get the virus under control without a mask mandate. “I trust Iowans to do the right thing, and I think they are doing the right thing.” (Many local officials want to require face coverings in their jurisdictions, but the governor has refused to allow local governments to enforce their own mask ordinances.)

The White House experts tried a different angle in the September 13 report.

• Establish a statewide mask mandate. COVID-19 is being brought into nursing homes through community transmission. Review and improve infection control practices at nursing homes to stop the introduction of COVID-19. Arkansas is a great example in the Heartland where statewide transmission has decreased through mask usage.

• In areas with ongoing high levels of transmission (red and yellow zones), use standard metrics to determine school learning options and capacity limits for bars and indoor dining.

Why Arkansas? That state’s Republican Governor Asa Hutchinson had initially resisted a mask mandate but changed course in July. Reynolds and Hutchinson were among five GOP governors who bragged in an early May guest column for the Washington Post, “Our states stayed open in the covid-19 pandemic. Here’s why our approach worked.”

The White House task force backed off from the word “mandate” in the September 20 report: “Ensuring mask utilization statewide will prevent unnecessary transmission and deaths in vulnerable communities.”

When another week passed with no new mitigation policies in Iowa, the task force’s September 27 report sounded the alarm about Iowa’s “vulnerable position.” Topping the new list of recommendations:

Test positivity and case rates have been sustained at the highest levels during the past four weeks, putting Iowa in a vulnerable position going into the fall and winter. Transmission is statewide with new hospital admissions increasing. Institute mask requirements statewide with reduced capacity for indoor dining and bars while expanding outdoor dining options. Use metrics like West Virginia to determine school learning and extracurricular activity options.

Reynolds and Pedati announced one significant policy change on September 29. A study of four school districts in Sioux County revealed that COVID-19 was much more prevalent in schools that didn’t require students and staff to wear face coverings. The logical conclusion would be to mandate masks in all Iowa schools. Instead, IDPH relaxed its guidelines for schools and many workplaces so people who had been in close contact with someone carrying COVID-19 wouldn’t need to quarantine if both people were wearing masks the whole time. The new rule contradicts guidance from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control.

Reynolds explained that she wanted to give school districts “flexibility.” If masks are effective, and people are wearing them properly, “then they shouldn’t have to quarantine for fourteen days. […] it really helps keep the kids in school, but it helps keep the kids in school in a safe and responsible manner.”

Wouldn’t it make more sense to reduce spread in schools by mandating masks, one reporter asked? “I think it’s a great incentive to move forward,” Reynolds replied. “I believe in Iowans, I believe they do the right thing.”

On October 4, the White House task force tried to impress on Iowa leaders that inaction was costing lives.

• Community transmission has remained high across the state for the past month, with many preventable deaths. […]

• Messaging to communities about effectiveness of masks is critical as many outdoor activities will be moving indoors with colder weather approaching. Masks must be worn indoors in all public settings and group gathering sizes should be limited.

• Work with rural communities to message masks work and protect individuals from COVID-19. In high transmission zones, limit indoor dining, bar hours, and expand outdoor dining options.

Reynolds took offense at the phrase “preventable deaths,” even though it’s objectively true that more Iowans would be alive today if our state had managed to reduce transmission rates months ago. She complained about the wording during an October 15 meeting with U.S. Health and Human Services Secretary Alex Azar.

In the October 11 report, the White House experts tried to drive home that Iowa is doing worse than states that have implemented “comprehensive mitigation efforts.”

• We have included cases, test positivity, and deaths by month in the back of your packet to show the time sequence in Iowa and the country as a whole. These demonstrate the impact of comprehensive mitigation efforts when implemented effectively and that partial or incomplete mitigation leads to prolonged community spread and increased fatalities.

• Community spread continues in both rural and urban areas of Iowa and it is critical that mitigation efforts increase to include mask wearing, physical distancing, hand hygiene, and avoiding crowds in public and social gatherings in private to stop the increasing spread among residents. […]

• There continue to be severe outbreaks among nursing home residents and staff; common sense mitigation efforts can prevent transmission among the vulnerable populations.

Again and again, Reynolds has claimed that protecting the most vulnerable was among her top priorities. Yet presented with evidence that uncontrolled spread is causing sickness and death in long-term care facilities, she’s not willing to inconvenience Iowans at lesser risk of severe health problems.

The governor’s mind seems closed. Echoing comments from at least a dozen of her press conferences (most recently on October 7), Reynolds told reporters on October 16

that her administration has implemented many recommendations from the White House task force. However, she said, “I have to balance it all. So I have to look at the lives and the livelihoods of Iowans, and that is about keeping our economy up and going. … We have to balance really mitigating coronavirus but also figuring out how we learn to live with it in a safe and responsible manner.”

Reopening “in a safe and responsible manner” has been a mantra for Reynolds since April. To paraphrase Joe Biden from his last debate with Donald Trump, Iowans aren’t learning to live with COVID-19 safely and responsibly. We’re learning to die from it.

The latest White House report, dated October 18, noted the increase in cases and test positivity: “Iowa had 238 new cases per 100,000 population in the last week, compared to a national average of 117 per 100,000.” It repeated the advice about “comprehensive mitigation efforts” to avoid “prolonged community spread and increased fatalities.” A new addition to the recommendations: “In red and orange counties, both public and private gatherings should be as small as possible and optimally, not extend beyond immediate family.”

Reynolds has kept up a busy schedule this week attending Republican campaign events around the state, mostly indoors and sometimes with only a fraction of attendees wearing masks.

On October 23, IDPH spokesperson McCoy provided a list of ways the state is following White House recommendations on communication, outreach, and testing. Those steps may be worthwhile, but clearly they are not bringing down new COVID-19 cases, hospitalizations, or deaths.

“WE HAVE TO GET THINGS BACK TO NORMAL”

Back in May and June, Reynolds often said she and top public health officials would base their approach on “what we’re seeing happening on the ground” around Iowa. Using data collected “right down to a zip code,” officials would “manage and do everything that we can to contain the virus.”

Yet as hospitalizations and deaths have climbed, the data have not prompted the governor to dial up mitigation policies–even in communities with massive outbreaks, like Buena Vista County in May.

Instead, Reynolds prioritized returning to “normal” life.

At one news conference in May where she announced more planned business reopenings, the governor reminded journalists that officials never promised Iowans would not get COVID-19. “That’s unrealistic, it’s unattainable. What we have to do is learn to live with it and manage the virus, and we have to get things back to normal.”

Defending the idea of allowing thousands of Iowa State fans from all over to attend home football games in Ames, Reynolds told reporters on September 10,

“As we learn to live with COVID-19 until we have a vaccine, we have to learn to live with it, and we have to bring some normalcy into our lives, and we can do that safely and responsibly. But we have to provide the information, if you’re an older adult, or if you have underlying conditions, then maybe you shouldn’t go to the game. But if you’re healthy, and you want to go, and we have the social distancing in place, and you want to put on a mask in addition to that, then I think there’s ways that we can move forward with that.”

The governor is well aware that resuming pre-pandemic habits contributes to community spread. She opened her September 29 news conference with remarks about rising case numbers in rural counties, particularly in northwest Iowa. Case investigation showed that no specific event or activity was fueling those numbers, Reynolds said. “Rather, as more people get back to life as normal, the virus is simply spreading from person to person during the course of normal daily activities.”

Yes, that’s precisely why the White House Coronavirus Task Force had been begging Iowa officials to limit activities that pose a high risk of transmission, like congregating in large groups, hanging out in bars, or eating indoors at restaurants.

Reynolds appears to believe that such sacrifices are too much to ask of Iowans, who can simply be trusted to “do the right thing.” During her opening remarks at an October 7 press conference, she noted that President Donald Trump’s illness showed “COVID-19 has the ability to reach all of us. […] But the president is also right: we can’t let COVID-19 dominate our lives.”

She then broached an uncomfortable fact: Iowa’s hospitalizations had just set a new record.

“THEY HAVE THE RESOURCES TO MANAGE THE NUMBERS”

In the early days of reopening in May, Reynolds declared that officials were “shifting strategies” on the pandemic, because “We now have identified that we have the resources available” to take care of Iowans needing hospital care. She has often bragged about how Iowa “flattened the curve” and prevented our health care system from being overwhelmed.

Many in the medical community are alarmed by the rise in hospitalizations and want the state to take more action to “turn off the faucet,” in the words of Dr. Jorge Salinas, the lead epidemiologist at the University of Iowa Hospitals and Clinics.

To hear Reynolds tell the story, hospitals are doing just fine, not worried at all.

Watch her opening remarks from October 7, the only televised press conference she’s held this month.

After agreeing with Trump (“we can’t let COVID-19 dominate our lives”), Reynolds acknowledged the rising case numbers and community spread, especially in northwest Iowa. The previous day, statewide hospitalizations set a new record at 444.

“This is disappointing news, and sadly, it’s what can happen when we are experiencing community spread,” Reynolds said. As she’s often done before, she emphasized that most who became severely ill were over age 60, or had pre-existing health conditions.

But fear not: Reynolds said health care providers across the state have “assured us that they’re able to manage the capacity, and they have the resources that they need, and most importantly, that they’re prepared.” She hailed the “unprecedented coordination and collaboration” among health care systems, which was allowing Iowa to manage the higher numbers. Over seven months, doctors and nurses have gained experience treating coronavirus and have access to new therapeutics and other ways “to help patients recover sooner.”

In sum, Reynolds said Iowa has “not approached the peak of our hospital capacity. Our health care system in Iowa is strong, and for that we are grateful.”

Fast forward two weeks. Hospitalizations had surged past 500. The governor’s communications director Pat Garrett provided this statement to the Des Moines Register’s Tony Leys on October 21:

“We have seen increased community spread across the country and it’s why Iowans, especially vulnerable Iowans, need to continue to take the necessary precautions to avoid exposure,” Garrett wrote. “The governor and her team are in regular contact with our hospital systems and hospital resources remain stable. The governor continues to encourage Iowans to wear masks, practice social distancing, wash their hands, and stay home when sick.”

Between campaign stops on October 22, reporters asked Reynolds about the trend. She asserted, “Right now the hospitals are assuring us that they have the resources to manage the numbers.”

It sounds like the governor is laying the groundwork to blame hospital leaders if the facilities eventually become overwhelmed.

The goal shouldn’t be to keep going until beds are filled up. By that time, it will be too late.

“IT’S LIKE TURNING A GIANT SHIP”

Bleeding Heartland interviewed two doctors on October 9 who have worked long hours treating COVID-19 patients. Dr. Michihiko Goto, an assistant professor of internal medicine and infectious diseases at the University of Iowa, described the trend in hospitalizations as “extremely alarming.” While some say Iowa still has more than 30 percent of hospital and intensive care unit beds available, capacity is “a very poor indicator of the state of the pandemic,” he told me.

Goto noted that the state of New York had 25 percent of hospital beds available in late March and April. Meanwhile, all the hospitals in New York City were overwhelmed. Similarly, Iowa never reached our hospital bed capacity in any region this spring. But when outbreaks in meatpacking plant sickened hundreds, Sioux City area hospitals became so crowded that some patients were transferred to Omaha facilities.

Furthermore, unoccupied beds don’t necessarily mean we have enough health care providers and support staff like nurses and respiratory therapists, Goto explained. When COVID is widespread in the community, there will be more absenteeism among health care providers, who “are also human” and will get sick.

Putting a positive spin on the hospitalization numbers (see also here), Reynolds has said not all people hospitalized with COVID-19 were hospitalized because of the virus. They may have come to the hospital for some unrelated reason (to have an elective procedure or a baby) and tested positive due to the hospital policy.

“It doesn’t matter,” Goto said. Those people are still “needing health care resources” and could potentially spread coronavirus in the hospital, even if asymptomatic. Dr. Eli Perencevich, an epidemiologist and infectious disease specialist at the University of Iowa, said “there’s no evidence” to support the governor’s assertion. The university has been testing all inpatients since at least June, if not earlier. But the hospitalization increase is happening now. “You can’t explain any of that away.”

Perencevich added that patients with COVID-19 remain at risk for complications, even if they came to the hospital for some other reason. For instance, a heart attack could be caused by previously undiagnosed COVID. Our statewide positivity rate suggests “We are significantly under-testing” in Iowa.

Reynolds has said hospital stays are shorter now than earlier in the pandemic. Goto described that comment as “superficial.” Those coming from nursing homes tend to have more complex medical problems and “very long” hospital stays, compared to younger people who may become ill. But younger patients still require a lot of resources when hospitalized.

Perencevich said even if hospital stays are slightly shorter than the spring, they are nonetheless very long. If you end up in an ICU, “you’re there for weeks.” In fact, length of stay for COVID-19 patients is “the most concerning thing” to him.

It’s like turning a giant ship, reducing hospitalizations. Because even if we turned off the spigot and had no transmissions for two weeks, hospitalizations would still rise, because people stay many weeks in the hospital.

Reynolds has touted improved treatments that keep more patients off ventilators. Goto wasn’t convinced. Remdesivir has “only a very marginal benefit.” A steroid treatment made some difference, but there is no cure for coronavirus yet. Even with the best available treatment, Goto expects more demand for ICU beds and ventilators. Prevention of new infections is always “much better than treatment.”

Perencevich couldn’t say whether fewer COVID patients need ventilators now. Admitting people earlier and getting them on oxygen helps. But heading into winter, the severity of illnesses may increase. “If winter makes this worse, we’re in a dire situation,” because we’re “already in a terrible situation.”

“WE ARE JUST ONE STEP BEFORE CATASTROPHE”

Is there any chance to reduce hospitalizations without a strategy to reduce community transmission? “Unfortunately, no,” said Goto. In New York City, “it happened so fast.” Iowa is seeing widespread community transmission and increasing health care utilizations. We’re not yet at the point where health care facilities can’t handle the demand, but “we are just one step before catastrophe. I just don’t see any effective strategy without mitigating the community transmission.”

How close are we to the point of hospitals not being able to care for Iowans who don’t have COVID-19 but may need inpatient treatment for other conditions? Goto wouldn’t be surprised to see some Iowa hospitals reaching that level of crisis within a few weeks. As influenza season progresses, it’s even more important to decrease community spread of COVID-19.

Perencevich predicted that some hospitals will have to cancel elective procedures again as they fill up with COVID patients. It all comes down to “a lack of attention to preventing community spread in Iowa.” If we don’t reduce transmission through a mask mandate, and don’t “get cases under control so our contact tracers can catch up,” and don’t keep K-12 schools remote in high prevalence areas, “then we’re never going to get out of this situation.”

The governor “says the right things, but she does’t come up with the right answer,” in Perencevich’s view. “The right answer is controlling COVID.” We can’t keep the virus from reaching higher-risk people or get back to enjoying bars and restaurants without eliminating COVID.

Perencevich worries hospitals will go bankrupt because they’ll fill up with COVID patients and won’t able to to continue profitable procedures like cardiac catheterizations or colonoscopies. Some hospitals have imposed pay cuts for staff. Mercy Iowa City just laid off employees and closed their mental health unit. “That’s because we didn’t control community COVID.”

“None of this is inevitable,” Perencevich added. More densely populated areas have gotten the virus under control through basic public health measures like mandatory face coverings, restricting large indoor gatherings, and “just being smart.”

By way of example, he cited Singapore, which had massive outbreaks in worker dormitories comparable to Iowa’s meatpacking plant outbreaks. Through good epidemiology, contact tracing, and mandatory face coverings, they contained the virus and kept hospitalizations and deaths down.

“We’re not learning from the rest of the world, unfortunately.” It’s a “scary situation.”

The biggest question Perencevich has for Reynolds and the IDPH leaders is, “What is the threshold where they’ll start to care?” Do we need to reach 1,000 hospital admissions? 800? “What’s their data-driven threshold” that would prompt Iowa leaders to require face coverings instead of recommending them?

I’ve put that question to the public health department a few times during the past two weeks and received no response. I will update this post as needed.

UPDATE: I missed Dolly Butz’s write-up of Reynolds’ stop in Sioux City on October 22 to campaign for Senator Joni Ernst.

“Right now, I think we’re gonna continue to remind Iowans what they need to be doing, work with our hospitals to make sure they’re doing OK and continue to learn to live with it,” Reynolds said. “Right now, I don’t anticipate doing anything, but it’s not to say that I wouldn’t in the future if I needed to. It just would be very, very targeted and mitigated, because we know how to do that with the data that we have.” […]

Reynolds said she puts her trust in the people of Iowa, whom she called “resilient” and “responsible.” Because of that mindset, Reynolds said 75 percent of the state’s children have been able to return to the classroom in a “safe and responsible manner.”

“They do the right thing. They’re safe,” she said of Iowans. “Because of that, we were able to keep over 80 percent of our workforce working and businesses open.”

She’s either delusional about the pandemic being under control or she’s trying to project an aura of confidence before an election. I don’t know which is worse.

Top image: Screenshot from Governor Kim Reynolds’ September 29 news conference.

4 Comments

IDPH and Reynold Spout the Wrong Message

Excellent article.

Governor Reynolds has her head in the sand. People don’t necessarily “do the right thing,” no matter how “Iowa-nice” they are.

Iowasmitten Fri 23 Oct 11:17 AM

To top it off...

…Reynolds has been strongly implying that Iowans who are old and/or have other extra risk factors are becoming sick with covid because we are too dumb to take appropriate precautions and/or still don’t care enough to have found out what precautions we should be taking. It’s hard to interpret Reynolds’ “advice” any other way.

***

“The governor said many new COVID-19 cases are among younger Iowans, who are generally at a lower risk for serious illness if they contract the virus. She said Iowans who are older than 65 or who have underlying conditions should be aware that the virus is spreading in the state.

“You need to really be conscientious of the community spread, you need to be conscientious of your outings, group gatherings, and so you can really manage your health by being aware of that,” she said, describing her message for that group.”

***

Really? Does she think we old and extra-risk Iowans are out here hitting the bars and partying down? Is she even remotely aware that just trying to buy essential groceries is an exercise in paranoia for many Iowans now, especially those who live in the often-rural areas where there is still lots of maskless shopping? Does she think we all, including Iowans who are seventy-plus, are able to use smart phones to order everything we need, and that we only go out because we’re perversely intent on getting sick?

I talked with one older Iowan who said one reason she’s determined to avoid covid and stay alive for the next two years is so she’ll be around to vote against Reynolds. I second that emotion.

PrairieFan Fri 23 Oct 12:21 PM

Borrowed last sentence on Facebook

I plagiarized that last sentence in PrairieFan’s comment for a Facebook post last night, and already have almost 100 likes.

merlin pfannkuch Sat 24 Oct 10:11 AM

Excellent!

Thanks for sharing that with BH!

PrairieFan Sat 24 Oct 3:56 PM