Larry Osweiler grew up in Keota, Iowa and now lives in Indiana. A graduate of the University of Iowa, he is an aficionado of Iowa treats found nowhere else: Pagliai’s Pizza, Sterzing Potato Chips, Maid-Rite’s, and kolaches from anywhere close to Cedar Rapids.

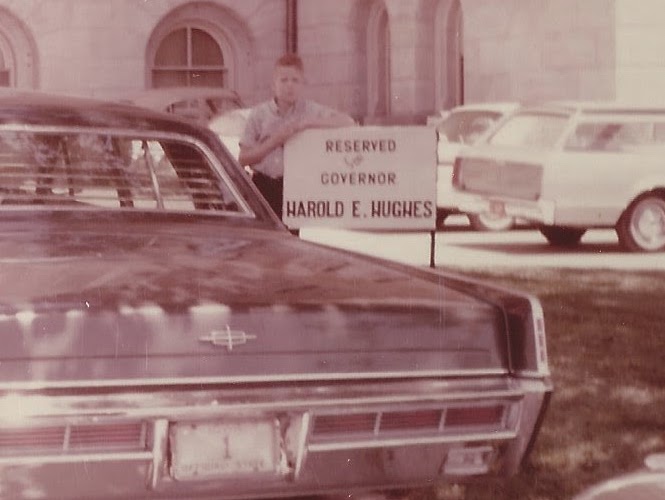

I got interested in Iowa politics in 1964 at the age of 8, when Governor Harold Hughes was running for re-election. I had sent for a picture of the governor and received a package from his office a few weeks later. I remember showing it to everyone on the school bus.

While waiting on the bus one afternoon, I remember Evan Hultman riding by on the back of a convertible with a Hultman for Governor sign on it. Hughes won with 68 percent of the vote. Hard to believe there was once a day when a Democrat would win a statewide race in Iowa by that large a margin.

I studied the book I’d received and memorized almost every state official. John Schmidhauser was elected to Congress from the first district. At our dinner table that election night, I wondered how my dad was so sure Lyndon Johnson was going to win the presidential election.

Continue Reading...