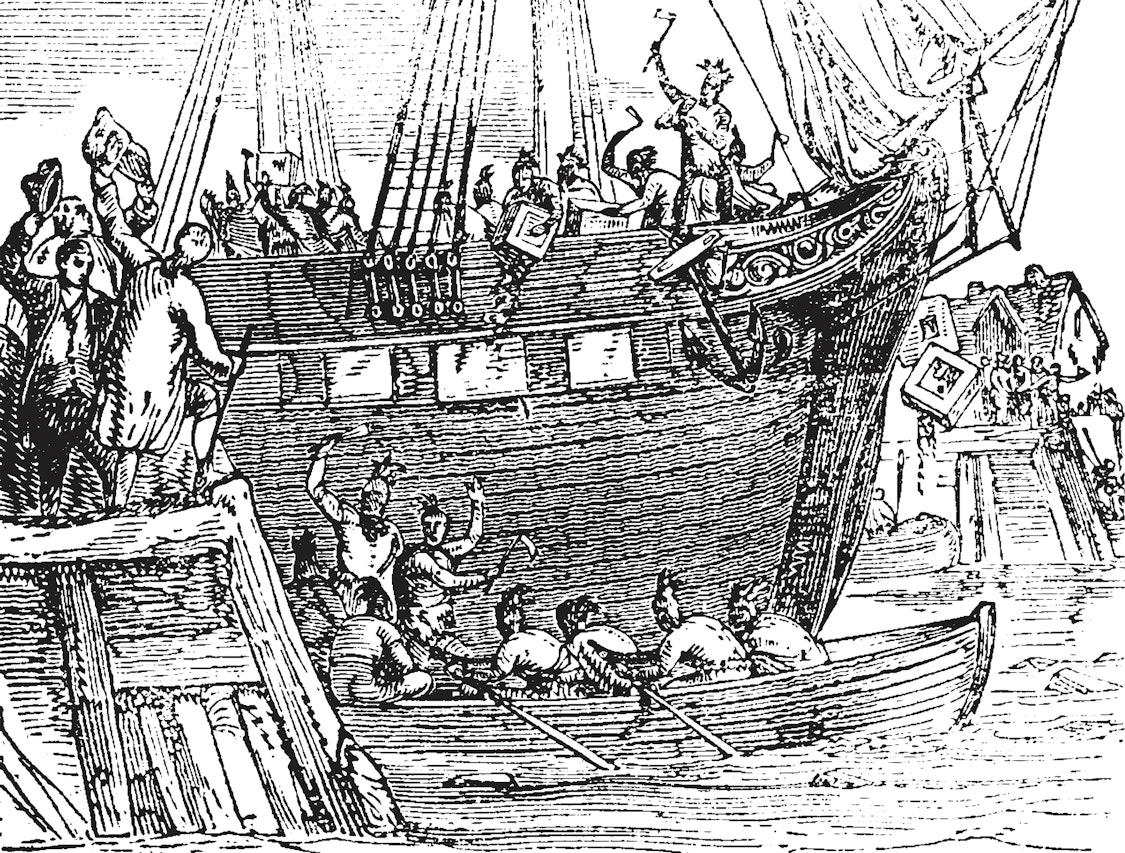

Boston Tea Party, vintage engraved illustration. Contributed by Morphart Creation to Shutterstock

Kurt Meyer writes a weekly column for the Nora Springs – Rockford Register and the Substack newsletter Showing Up, where this essay first appeared. He serves as chair of the executive committee (the equivalent of board chair) of Americans for Democratic Action, America’s most experienced liberal organization.

I’ve never been a big tea drinker, preferring coffee, several mugs daily. I will modify my beverage choice, however, on one day in mid-December to celebrate an anniversary. December 16, 2023, marks 250 years since the Boston Tea Party, a milepost in our nation’s march toward independence.

Since first encountering the Boston Tea Party in grade school, the story has always held a certain fascination: Rowdies disguised as Native Americans board a ship in the Boston harbor and toss the cargo overboard, thumbing their noses at the Brits. Five points I stumbled across in researching this event.

First, this was a well-planned action, not a spontaneous outburst. Around 10:00AM on December 16, a meeting was held at Boston’s Old South Meeting House to discuss a course of action. Between 5,000 and 7,000 people attended, not only Bostonians, but also people from neighboring towns. Shouts of “Who knows how tea mingles with sea water?” and “Boston Harbor, a teapot tonight!” suggest plans were emerging.

Between 60 to 90 men masquerading as Mohawks or Narragansett Indians, symbols of freedom, arrived at the wharf around 7:00PM armed with hatchets and axes. Disguises were simple, blackened faces and blankets, enough to hide their identities. Within three hours, 340 chests of tea were opened and dumped into the harbor. As the tide went out, boys spread the tea making it all unsalvageable, drifting out to sea.

Second, this event wasn’t called a “tea party” until five decades had passed. For years, the rather bland title was “destruction of the tea.” The earliest newspaper reference to the “Boston Tea Party” appeared in 1826. The event was often ignored in early American Revolution accounts, one historian noting American writers hesitated to celebrate property destruction. In the 1830s, two books, A Retrospect of the Tea-Party and Traits of the Tea Party, popularized a new nickname, which has now lasted almost two centuries.

Third, the cast—both on- and off-stage players—included many big names. For example, one prominent actor was Paul Revere, who rode horseback to Manhattan, New York, to tell of Boston happenings. Samuel Adams, more recognizable today as a beer brand, was among the morning meeting facilitators. Afterward, he publicized and defended the resulting actions. His second cousin, John Adams, wrote, “This Destruction of the Tea is so bold, so daring, so firm… and so lasting, that I can’t but consider it as an Epoch in History.”

Abigail Adams predicted, “The flame is kindled . . . Great will be the devastation if not timely quenched or allayed by some more lenient measures.” In the aftermath, the Adamses, like many colonists, considered tea an unpatriotic drink. Tea drinking declined during and after the Revolution, with a corresponding shift to coffee. Six months later, George Washington wrote: “The cause of Boston …ever will be considered as the cause of America.” His immediate reaction to the event was less supportive, however, since for many colonial elites, private property was held sacrosanct. Benjamin Franklin suggested reimbursing the British East India Company for their lost tea, although no one took him up on it.

Fourth, it was a major financial loss. Protestors destroyed an estimated 92,000 pounds of tea, with a present-day value of almost $2 million. This loss was of a scale that couldn’t simply be ignored.

Fifth, downstream implications were significant. Historians frequently employ expressions like “lighting a fuse,” “the most important event leading up to the American Revolution,” and “the first unofficial ‘Declaration of Independence.’” After years of dithering, tea destruction demonstrated that colonists could actually do something.

As an act of defiance, the Boston Tea Party’s impact was elevated to “defining-moment status,” an example of what eventually became a classic American trait. Known by many names—civil disobedience, mob rule, “taking matters into one’s own hands”—actions, including illegal actions, are justified by summoning a higher code of fairness, integrity, and honor.

So, to celebrate this noteworthy anniversary, on December 16, 2023, I’ll be drinking tea. Won’t you join me?

2 Comments

most importantly

was that is was an anti-monopoly movement

https://www.thebignewsletter.com/p/the-boston-tea-party-was-a-protest

dirkiniowacity Thu 14 Dec 6:58 PM

More details...

JP Bubendorfer Thu 14 Dec 8:15 PM