Dr. Emily Boevers is a Readlyn farm kid, mother of three, and physician practicing in Iowa. This essay first appeared in the Waverly Democrat.

Property “ownership” is surprisingly complicated. Since feudal times when all land belonged to kings, to global wars that claimed land by force and displaced native populations, to modern concepts about private deeds, covenants and easements—property rights are nuanced. The law bundles the privileges of land ownership as a right to exclude others from a space, to protect or to exploit property for one’s own benefit, to pass it on to heirs and to not have it unlawfully taken or damaged. Enforcement of the rights that come with land title are an honored, but dynamic, legal tradition.

Today, limited options exist to legally seize, use or redistribute property owned by another. Zoning laws are one example of limitations on property use. Voluntary easements grant another the opportunity to use one’s property for limited purposes. Eminent domain allows the non-consensual taking of private land so long as landowners are justly compensated and public good is served.

It is likely through enforcement of eminent domain that the carbon-capture pipeline will ultimately wind its way through Iowa. In June 2024 the Iowa Utilities Board (since renamed the Iowa Utilities Commission) determined that the project qualified as “public use.” The board members concluded that the pipeline’s potential public benefits outweighed private and public costs. Therefore, landowners who do not sign voluntary easements for Summit Carbon Solutions’ pipeline could still be subject to non-consensual use.

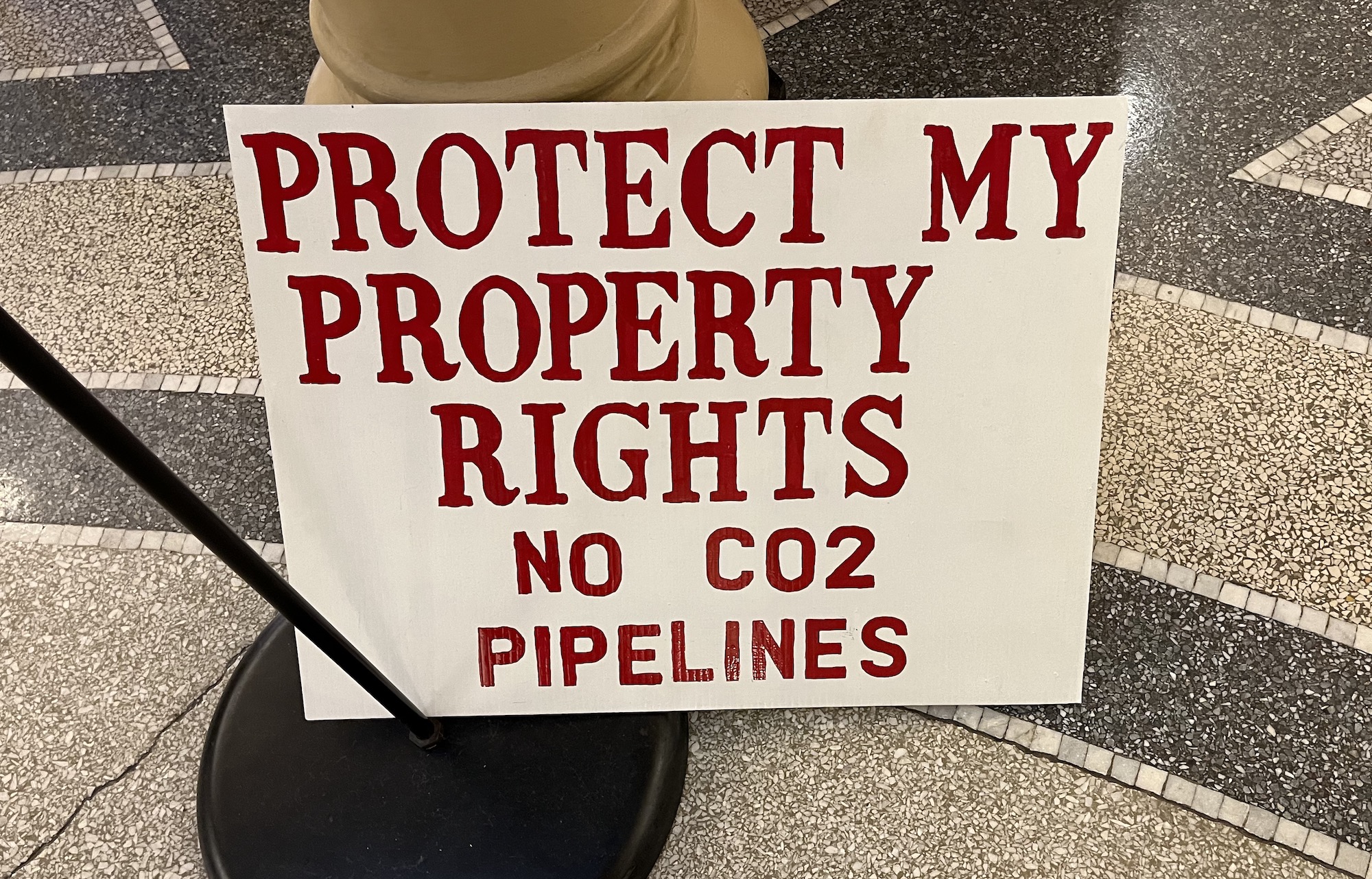

Since the Summit Carbon Solutions CO2 pipeline was proposed, Iowans have voiced their opposition to using eminent domain to seize private property for that purpose. A 2023 poll showed a whopping 78 percent of Iowans opposed using eminent domain laws for carbon-capture pipelines. As a result, whether or not the profits and business purposes of the private company meet the public use threshold has been hotly debated.

The concept of using eminent domain for cross-country pipelines has been applied in the natural gas industry, which provides electricity to cook food and heat homes. The CO2 pipeline has the potential to open more markets for corn sellers by alleviating an underlying problem with ethanol development: the by-product of carbon emissions and their negative effect on the environment. The Summit Carbon corporation undoubtedly stands to benefit from the endeavor. Landowners who grant Summit an easement may be awarded annual stakeholder payments.

But what’s in it for the average Iowan? The hope of a better economy, the promise of corporate profits, and the unknown of potential complications of buried CO2 pipelines, which can include health risks like chronic headaches, nausea, or asphyxiation; environmental contamination to air, water and soil; and corrosion risks from the pipes and carbon dioxide.

Iowa is on the brink of an important decision, and as the 2026 legislative season kicks off this month, we must all watch closely—and follow the money. Public sentiment has been clear. During the 2025 legislative session, some steadfast legislators from both sides of the aisle passed House File 639 to add additional insurance safeguards for pipeline properties and stricter eminent domain guidance. However, Governor Kim Reynolds vetoed that bill.

Now, the same elected officials will have another opportunity to decide: Will individual property rights rule? Will the corporate pipeline forge ahead? Will any of this resuscitate our failing state economy?

Whatever goals we support, property rights have multigenerational impacts. If Summit Carbon is granted the legal authority to use private property for their business interests, the message will be loud and clear: Iowa is for sale, and we need only look at the campaign contributions to see who sold it.

If the state allows a corporate pipeline to run through family farmlands, who will bear the legal responsibility for upkeep and stewardship? If a pipeline leaks in 20 years, who will enforce clean up and reparations? If Iowa’s contamination, cancer and healthcare crisis spirals further out of control—who will step up to make the decisions that favor everyday Iowans?

These are not academic questions: they have a real and immediate policy impact. Ultimately, these questions prove why it is important to elect wise legislators, governors and boards to develop long-term policy solutions—and recognize human values, business opportunities and public interests in the process. We must start thoughtfully, but urgently, building the Iowa we want to live and raise our families in.

5 Comments

appreciate Emily and company

keeping up the fight here. but what we really need is Iowa Dems to except that ethanol is a losing bet in a world racing toward electrification and decarbonization.

So far we don’t really have a viable plan from Iowa Dems for our future economy but at least they could take up the fight of pushing to renew Biden’s push for clean energy and stop pushing Iowa’s version of “clean” coal….

dirkiniowacity Sat 3 Jan 3:42 PM

Congratulations...

…to the determined Iowans who have made impressive progress in fighting the carbon-pipeline-eminent-domain behemoth. As many of us have learned the hard way, even the most lopsided results of Iowa public-opinion polls can mean nothing unless they are accompanied by very hard work. Thank you to Emily and all those who are doing the very hard work.

PrairieFan Sat 3 Jan 4:40 PM

Mike Klimesh

is the Iowa Senate Majority Leader, who has become the major impediment to eminent domain legislation. He thinks he can do this politically because there is no pipeline in his district. So he thinks his constituents won’t care. I encourage anyone reading this who lives in Winneshiek, Allamakee, or Clayton County to send an email to Senator Klimesh telling him you do care what happens to other Iowans. His email is mike.klimwshQ@legis.iowa.gov.

Wally Taylor Sun 4 Jan 9:42 AM

Thank you, Wally Taylor

I hope your good advice will be followed by Senator Klimesh’s constituents. And I hope his bizarre plan to expand the pipeline routes and inflict fear on many more landowners will get the ridicule and bill-killing it deserves in the Iowa House, if not in the Senate.

PrairieFan Mon 5 Jan 12:22 PM

Yikes!

My computer made some typos on Mike Klimesh’s email. It is mike.klimesh@legis.iowa.gov.

Wally Taylor Mon 5 Jan 3:26 PM