Last week, Governor Terry Branstad’s office rolled out a new “streamlined application form for those seeking a restoration of their voting rights,” so that “Iowa’s already simple voting rights restoration process will become even more efficient and convenient.”

“Simple,” “efficient,” and “convenient” wouldn’t be my choice of words to describe a process used successfully by less than two-tenths of 1 percent of affected Iowans since Branstad ended the automatic restoration of voting rights for felons five years ago. The governor’s first stab at simplifying the system in December 2012 did not significantly increase the number of Iowans applying to get their rights back. Three years after that change, fewer than 100 individuals out of roughly 57,000 who had completed felony sentences since January 2011 had regained the right to vote.

The new double-plus-streamlined process seems unlikely to produce a large wave of enfranchised Iowans, because it leaves intact major barriers.

The latest announcement looks like an attempt to convince Iowa Supreme Court justices that they need not intervene to give tens of thousands of felons any realistic hope of exercising a fundamental constitutional right again.

THE FIRST “STREAMLINED” VOTING RIGHTS RESTORATION PROCESS

An estimated 100,000 Iowans had regained their voting rights between July 2005, when Governor Tom Vilsack allowed the process to begin without a formal application from the felon, and January 2011, when Branstad rescinded Vilsack’s order on his first day back in the governor’s office. As of June 2012, “less than a dozen” people had regained their voting rights out of some 8,000 Iowans who had completed felony sentences or probation since Branstad’s action, Ryan Foley reported for the Associated Press.

The policy kept about 13,000 Iowans from being eligible to vote in 2012. Shortly after that year’s general election, a delegation from the NAACP lobbied the governor to rethink his approach, which disproportionately affected African-Americans. Reporting on that meeting, Radio Iowa’s O.Kay Henderson paraphrased the NAACP’s Iowa/Nebraska chapter president Arnold Woods, Jr., as saying “Branstad indicated one change in the process — that a felon need only be current in paying restitution rather than requiring them to pay it all before they can apply to get their voting rights back.”

Indeed, about a month after discussing the issue with NAACP representatives, Branstad announced a “streamlined” process for Iowans to regain their voting rights. From the statement released on December 28, 2012:

“When an individual commits a felony, it is fair they earn their rights back by paying restitution to their victim, court costs, and fines,” said Branstad. “Iowa has a good and fair policy on the restoration of rights for convicted felons, and to automatically restore the right to vote without requiring the completion of the responsibilities associated with the criminal conviction would damage the balance between the rights and responsibility of citizens.”

“Too often victims are forgotten and it is important victims of felonies and serious crimes receive their restitution,” said Reynolds. “The updated process for restoration of voting rights streamlines the process for applicants while ensuring we are mindful of the victims of the crime.”

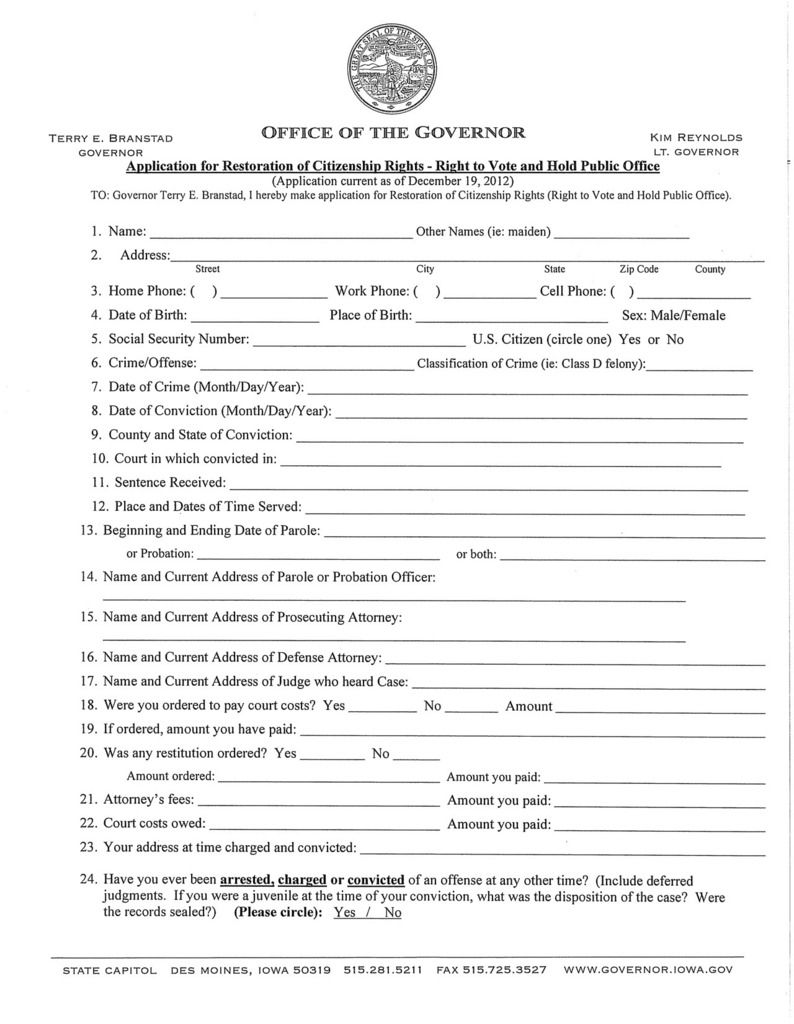

The updated application includes:

• Simplified instructions for applicants

• Clarification of the current policy about submitting documentation to show an applicant completed paying their fines, restitution and court costs or has been making consistent payments in good faith

• Provides contact information so applicants can obtain free resources to help them fill out the application

• Removes the requirement for a credit history check for the voting application

Provides a more detailed “checklist of materials” to help applicants turn in a completed application

A year after the new process went into effect, Foley reported that “Branstad used his power of executive clemency to restore the right to vote and hold public office to 21 offenders who applied in 2013, compared to 17 in 2012 and two in 2011.” Only a few dozen more felons regained their voting rights during 2014 and 2015.

That the “streamlined” application changed little is not surprising. People who have committed felonies often have trouble finding secure housing or a job to cover essential costs of living. Even if they had the time and money to chase down all the information needed to fill out the 29-question form, most felons lack enough disposable income to make regular payments toward debts associated with their convictions.

WHAT’S NEW IN THE LATEST “STREAMLINED” PROCESS

An April 27 press release highlighted the first stage in a “review of all four of the executive clemency applications to streamline the process and find government efficiencies.”

Gov. Terry E. Branstad and Lt. Gov. Kim Reynolds released a one-page streamlined application form for those seeking a restoration of their voting rights. This form is less than one page in length and reduces the number of questions from 29 to 13. With this new application form, Iowa’s already simple voting rights restoration process will become even more efficient and convenient.

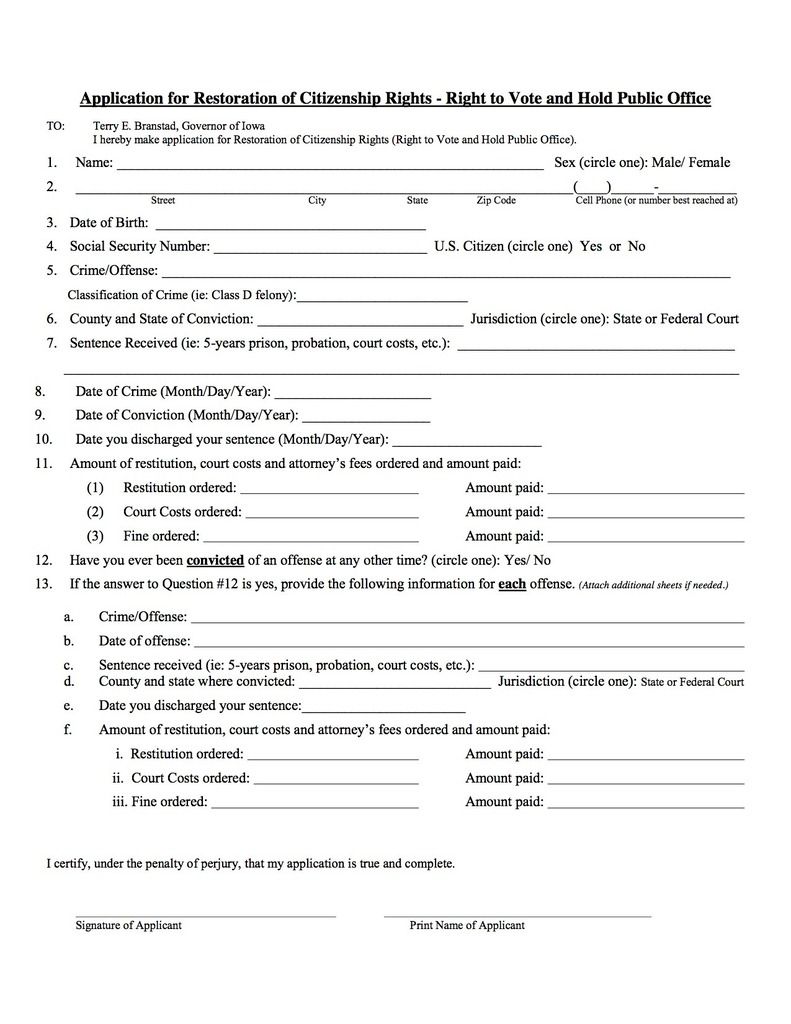

Here’s the two-page application to have voting rights restored following the December 2012 “streamlining”:

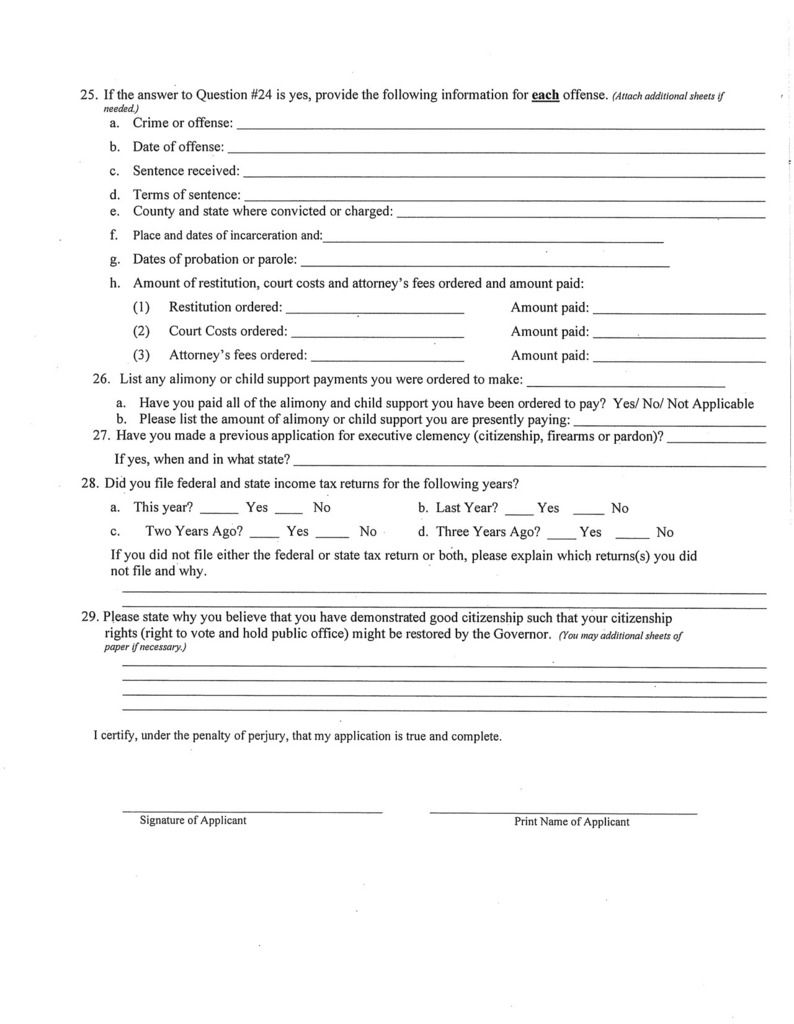

Here’s the application released on April 27:

The new application is shorter, partly for substantive reasons and partly because of clever formatting.

Ten line items from the old form were eliminated. Those asked applicants to provide:

• the place and dates of time served for the conviction;

• the name and current address of the parole or probation officer;

• the name and current address of the prosecuting attorney;

• the name and current address of the defense attorney;

• the name and current address of the judge who presided over the case;

• the applicant’s address at the time of the felony charge and conviction;

• any alimony or child support payments the applicant had been ordered to make;

• information about any previous applications for executive clemency (voting rights, access to firearms, or pardon);

• information on whether the applicant had filed state and federal tax returns during the previous four years; and

• an answer to an open-ended question about why “you have demonstrated good citizenship such that your citizenship rights (right to vote and hold public office) might be restored by the governor.”

Incidentally, the NAACP’s amicus brief for a voting rights case before the Iowa Supreme Court cited that last question as an example of “an unfair barrier for those seeking restoration,” because “There are no standards or safeguards in place to guarantee that reviewers will not reject an application based on an ‘unsatisfactory’ answer.”

Taking out those ten questions will somewhat reduce the time and expense required to complete an application. Another revision worth noting: the new form asks applicants about prior convictions, whereas the old form asked for prior arrests and charges as well as convictions.

But hang on–the governor’s press release talked about reducing the number of questions from 29 to thirteen (not nineteen).

Whoever redesigned the form accomplished that goal by consolidating some questions onto fewer lines.

Question 3 asks for the applicant’s address and phone number. Those were separate questions on the old form.

Question 6 asks for the county and state of the person’s felony conviction as well as the jurisdiction (state or federal court). Those were separate questions on the old form.

Question 11 asks about the amount of restitution, court costs, and attorney’s fees the applicant was ordered to pay and have paid. The old form sought the same information in five questions.

By the way, the new form seems to use “attorney’s fees ordered” and “fine ordered” interchangeably (questions 11 and 13). I don’t know whether the governor’s office views those two things as synonymous or whether someone forgot to replace all mentions of “attorney’s fees” with “fines.”

Keeping the new application short was clearly a priority. The April 27 press release twice refers to the form fitting on a single page. A few other space-saving measures made that possible. For instance, Question 12 asks about prior convictions without the explanation provided in the corresponding question on the old form (“Include deferred judgments. If you were a juvenile at the time of your conviction, what was the disposition of the case? Were the records sealed?”). Question 13 asks for details on previous convictions but eliminates the lines asking for “terms of sentence” and “place and dates of incarceration.”

WHAT DIDN’T CHANGE ABOUT THE PROCESS

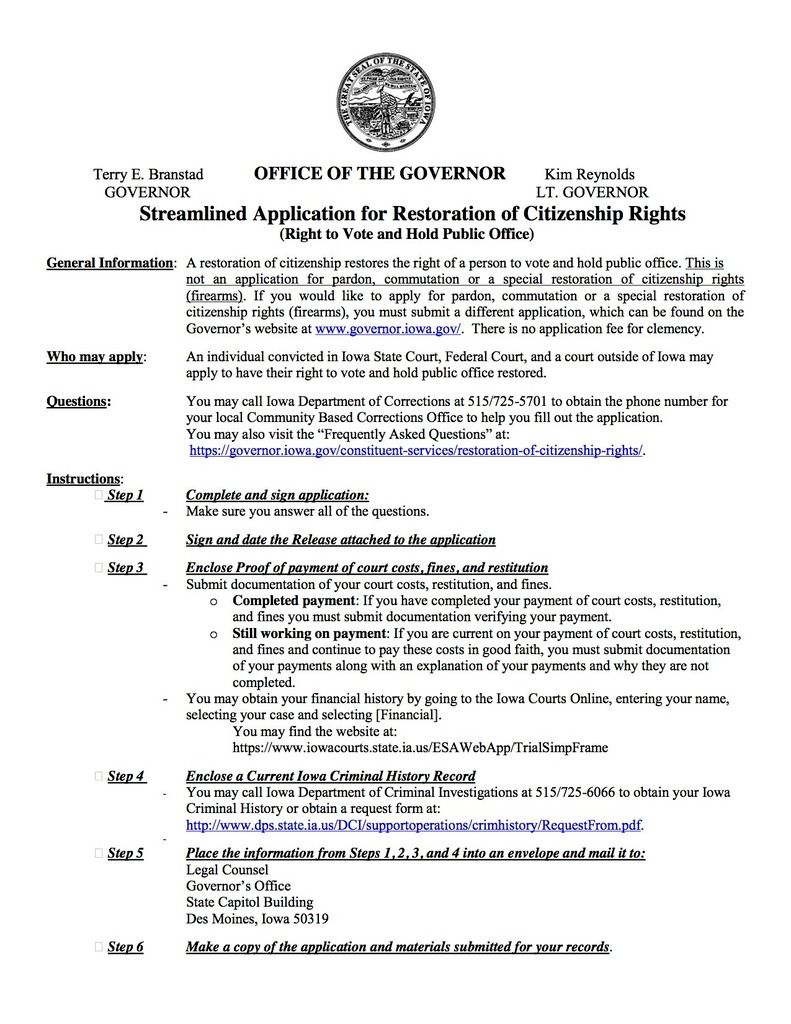

The governor’s press release last week asserted, “Iowa’s already simple voting rights restoration process will become even more efficient and convenient. […] The new application form contains simple instructions, clearly explains the information needed to initiate the process to restore one’s voting rights, and includes contact information for applicants who would like free assistance with filling out their application.”

At the end of this post, I’ve enclosed the new instructions page. As promised, it spells out what applicants need to do and whom they can contact for help.

Too bad “free assistance with filling out the application” doesn’t address the largest obstacle facing felons seeking permission to vote again. Most people who commit crimes do not have several hundred dollars lying around to cover court costs or fines. As long as Branstad requires felons to show they have settled such debts or are making regular payments toward that end, Iowa’s voting rights restoration process will be akin to a poll tax, disproportionately affecting people of color.

These two paragraphs from the April 27 statement raised many more questions:

“When individuals commit felonies, it is important that they demonstrate that they have fully satisfied their sentences and have paid their court-imposed financial obligations and be current on restitution if it’s required before receiving their voting rights back,” Branstad said. “This straightforward application form makes it easier for both the offender and the State of Iowa to put those eligible for a restoration of voting rights on the path back to the voting booth without compromising the integrity of the criminal justice system.”

“This newly re-designed application form strikes a balance between ensuring that offenders have demonstrated their ability to regain their voting rights, while also creating a more user-friendly process for offenders who would like their voting rights restored,” said Reynolds. “This application form is just another example of our administration’s commitment to promote fairness for the victims of crime while being mindful that rehabilitated offenders should have an opportunity to receive clemency.”

At this writing, I have not received answers to the following questions sent to the governor’s office on April 27. I will update this post as needed.

1. How many Iowans who have not committed crimes owe fines or fees to the state?

2. How many Iowans who have committed misdemeanor crimes owe fines or court costs?

3. Since other Iowans who owe fines or fees to the state or the court system are not deprived of their voting rights, why does the governor believe this condition should be attached to felons who want to participate in elections?

4. Many felons were never assessed any restitution payments. Why not create a process that automatically restores voting rights to such people?

5. Lt. Gov Reynolds speaks of “fairness to the victims of crime,” but many felons committed crimes that have no specific victim. Why not create a process that automatically restores voting rights to such people?

6. On a related note, does “fairness to the victims of crime” refer only to victims who are owed monetary restitution? Or do the governor and lieutenant governor see some kind of psychic benefit to victims in knowing that their offender is unable to vote for life?

7. Lt. Gov Reynolds speaks of opportunities for “rehabilitated offenders.” Do she and Governor Branstad think it is possible for an offender to be rehabilitated while also owing money? Or does someone have to settle all debts to be truly rehabilitated?

8. Why doesn’t the governor’s office set up a system for routinely checking who has paid court costs so that those people’s voting rights can be restored without a cumbersome application process?

9. Gov. Branstad speaks of the integrity of the criminal justice system. Yet most states have a more straightforward process for restoring voting rights to people who have completed prison terms or probation for felonies. In what way does that more expansive approach compromise the integrity of the criminal justice system in such states?

10. Lt. Gov Reynolds speaks of striking “a balance.” What convinced the governor that the previous process was out of balance (too difficult for offenders to navigate)?

11. To outside appearances, it looks like the new streamlined process is a reaction to the publicity surrounding the Griffin v. Pate lawsuit now pending before the Iowa Supreme Court. Can you comment on any connection between that court case and the decision to revise the voting rights restoration application?

IS THE NEW POLICY A GESTURE TO THE IOWA SUPREME COURT?

The governor’s latest action could be seen as a rebuke to Iowa Secretary of State Paul Pate. Our state’s top elections administrator has been telling everyone who will listen that the current process for regaining voting rights is not “difficult” or “challenging.” Now Branstad has tacitly admitted the status quo was not “efficient and convenient” enough, prompting changes to strike a better “balance.”

The Iowa Supreme Court heard oral arguments on March 30 in a case challenging the idea that all felonies should be considered “infamous crimes,” for which citizens lose their voting rights under the Iowa Constitution. Arguing on behalf of plaintiff Kelli Jo Griffin, the American Civil Liberties of Iowa holds that her “prior felony conviction for a nonviolent, general intent drug offense unrelated to voting” should not disqualify her from participating in elections.

In theory, the justices don’t need to consider Branstad’s process for restoring voting rights as they weigh whether to interpret the constitutional phrase “infamous crimes” in a new and more limited way.

However, justices may consider the real-world impact of the governor’s 2011 executive order, which leaves approximately 57,000 Iowans unable to vote and will continue to affect thousands more every year, with racially disparate impacts.

Responding to my request for information last month, a Branstad staffer emphasized how much time people in the governor’s office spend working on applications to regain voting rights. The fact remains: more than 99.8 percent of Iowans who have completed prison terms or probation for felonies since January 2011 do not have the right to vote.

Some of Pate’s recent comments sounded like an indirect threat to Supreme Court justices: if you allow thousands of convicted criminals to vote, there will be big political fallout. Three justices who might be sympathetic to Griffin’s appeal will be up for retention on this November’s statewide ballot.

On the flip side, last week’s press release struck me as an indirect promise to those justices: don’t worry, you don’t need to do anything drastic. The governor is on top of this problem and will help more rehabilitated criminals get their voting rights back.

Let’s be generous and assume 100 people per month are able to use the newly “streamlined” process successfully. (That would be more voting rights restorations every month than Branstad issued during the first five years after his executive order.) By the time of this November’s election, nearly 99 percent of all Iowans who had completed felony sentences since January 2011 would still be disenfranchised.

The most “efficient and convenient” policy would not make the right to vote contingent on a person’s ability to pay fines or fees of any kind. But we’ll never get that from this governor or from his preferred successor Reynolds. Anyway, Branstad got the headlines he wanted last week. Time will tell whether the latest streamlining is any more effective than what the governor implemented more than three years ago.

Appendix: Instructions page for Iowa’s new application for voting rights, released on April 27.