Iowa’s Revenue Estimating Conference delivered bad news yesterday. Revenues are lagging so far behind projections that even after enacting huge spending cuts in February, the state is on track to have a shortfall of $131 million at the end of the current fiscal year. Next year’s revenues are being revised downward by $191 million as well.

Governor Terry Branstad, Senate Majority Leader Bill Dix, and House Speaker Linda Upmeyer quickly announced plans to use the state’s cash reserves to cover the gap. Dix’s written statement explained, “We must not cripple our schools, public safety and many other essential services with further cuts this year. Our savings account exists for moments such as this.”

Two months ago, many Democratic lawmakers advocated dipping into “rainy day” funds as an alternative to the last round of painful reductions to higher education, human services, and public safety. At that time, Republican leaders portrayed such calls as irresponsible. A spokesperson said Branstad “doesn’t believe in using the one-time money for ongoing expenses.” Now, the governor assures the public, “Iowa is prepared,” thanks to hundreds of millions of dollars in the state’s cash reserves, and Dix boasts about the supposedly strong GOP leadership that filled those reserve funds.

Republican hypocrisy on state budget practices is irritating and all too predictable. But that’s not my focus today.

While transferring funds from cash reserves will solve the immediate problem, it won’t answer some important questions about how we got into this mess.

1. Why did lawmakers base the current-year budget on unrealistic income projections?

Predicting state revenues is not an exact science. Even the best professionals will sometimes get the numbers wrong. The last time Iowa’s revenues fell way short of projections was during the “Great Recession,” which caused “the largest collapse in state revenues on record.”

As others have pointed out, the current budget “pinch” is “not common,” because it is happening during a period of economic growth.

The shaky foundation of Iowa’s fiscal year 2017 budget was not on my radar until the three-member Revenue Estimating Conference announced in December that receipts were tracking well below previous expectations. Branstad administration officials and statehouse Republican leaders spent most of January negotiating a deal to bridge the gap by cutting more than $110 million from current-year expenditures.

I have since learned from Iowa State University economist Dave Swenson that the shortfall was easily foreseeable. Swenson observed in January that the Revenue Estimating Conference had assumed 7.2 percent growth in personal income tax receipts for fiscal year 2017, even though Iowans’ personal income had not collectively grown by more than 5 percent in any year during the previous decade.

Noting the conference’s revised estimate of 5.8 percent personal income tax growth (two columns to the right of the figure highlighted in purple), Swenson asked a prescient question.

Indeed, we just learned that they were off by $131 million more this year.

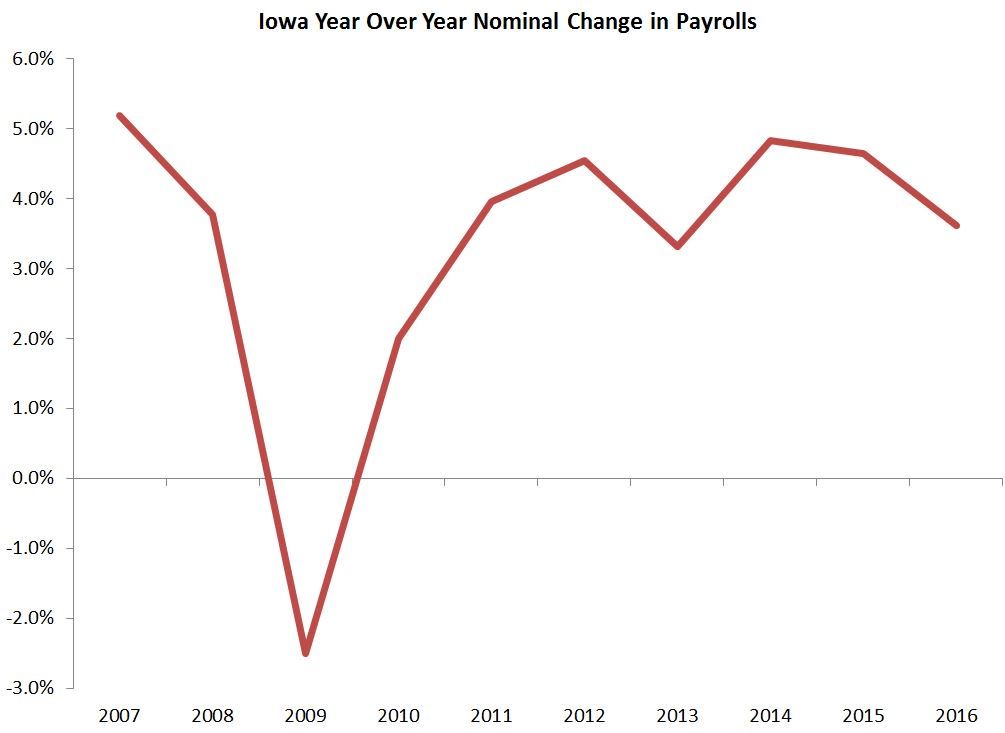

Swenson commented again yesterday that Iowa’s revenue shortfall “is a function of unrealistic tax growth expectations” built into the budget. Even in December, the conference predicted 5.8 percent growth in personal income tax collections during fiscal year 2017. Personal income hadn’t increased by that much annually during the past decade, as shown by this graph:

Branstad and Republican lawmakers aren’t solely to blame for this predicament. Democrats, who controlled the Iowa Senate last year, also agreed to a 2017 budget based on overly optimistic revenue projections. Presumably they were trying not to short-change education and other worthy services. Unfortunately, they only managed to delay the pain.

The Revenue Estimating Conference is supposed to be insulated from political pressure. We need to understand where last year’s “incredible” assumption of 7.2 percent income tax growth came from in order to prevent future mid-year budget crises.

2. How much did the new manufacturing sales tax break contribute to the shortfall?

Yesterday, several statehouse Democrats blamed “corporate tax giveaways” for the latest budget crunch. The Iowa Fiscal Partnership has patiently explained many times that business tax credits have created an ongoing, “self-inflicted” revenue shortfall. State Representative Chris Hall, the ranking Democrat on the House Appropriations committee, laid out some of the numbers in a January memo.

No question, Iowa’s business tax breaks are very expensive, costing the state roughly $600 million during fiscal year 2017. But most of those policies have been on the books for years. The Revenue Estimating Conference has not missed the mark by so much until now.

Only one big new business tax cut went into effect in 2016: a sales tax break for manufacturers.

O.Kay Henderson touched on that issue in her report for Radio Iowa yesterday:

David Underwood, a retired businessman from Mason City, is the other member of the panel that sets the official estimate of state tax collections. Underwood said during the meeting that he’s surprised there’s not more income growth being shown on the 2016 personal income tax returns Iowans have filed so far.

“And the sales tax continues to be perplexing in Iowa,” Underwood said. “It’s difficult to believe there’s that small a level of growth…It doesn’t really make a lot of sense.”

More than a third of all the revenue collected by the state comes from the state sales tax. Sales tax collections are running not quite even with a year ago. Experts cite the shift to online purchases, where customers often can avoid paying state sales taxes.

In addition, lawmakers last year erased the state sales taxes manufacturers paid on goods that are “consumed” during the manufacturing process, things like bolts, hydraulic fluid and drill bits.

Most Iowa media didn’t pay enough attention to that manufacturing sales tax break when it was under consideration.

When attempting to enact this tax exemption through administrative rule-making–an unprecedented power grab–the Iowa Department of Revenue predicted that manufacturers would save $35.1 million on state sales taxes during fiscal year 2017.

Jon Muller challenged the department’s assumptions. In an October 2015 guest post for this site, he speculated that the annual cost of the new sales tax break could be $80 million or more.

This is an ongoing tax cut of increasing value. […]

The non-partisan Legislative Services Agency (LSA), the policy analysis arm of the General Assembly, reviewed the Department’s methodology. One of LSA’s responsibilities is to act as a check on fiscal impact estimates provided by Executive Branch agencies. LSA provided some disturbing comments in the October 13 edition of “Administrative Rules – Fiscal Impact Summaries”:

https://www.legis.iowa.gov/docs/publications/FA/698692.PDF

“The current rule excludes supplies from the definition of replacement parts and specifically limits the exemption to “tangible personal property with an expected useful life of 12 months or more.” The new rule defines tax exempt equipment to include “supplies that do not qualify as replacement parts, such as drill bits, grinding wheels, punches, taps, reamers, saw blades, lubricants, coolants, sanding discs, sanding belts, and air filters.” The Department conducted a survey of 17 manufacturing companies “regarding purchases of relevant items (such as oils, greases, hydraulic fluids, coolants, filters, abrasives, and lubricants).” It is not clear whether the other supplies being added to the exempt equipment definition were also addressed in the survey. It is not clear whether the 17 companies included in the survey was a broad enough sample to represent expected usage of the exemption in the future.”

There’s a fair bit of nuance in that statement. First, keep in mind, the Department built its estimate on a survey of 17 companies, all of whom benefit if the rule is implemented. Secondly, we don’t even know if the survey itself was broad enough, either in terms of the number of firms surveyed or the content of the survey itself. In a previous estimate provided by the Department, they disclosed that some 2,000 companies will receive this tax cut. Related to that fact is the LSA’s most disturbing reaction to the fiscal implications of the rule:

“In addition, LSA has not been able to reconcile this estimate with the Department’s previous estimates regarding similar legislative proposals.”

In 2013, the Department employed a different methodology for the same tax cut. The Department provided a “lower bound” estimate of $32.7 million for FY 2017 and an “upper bound” estimate of $78.1 million. It would appear the Department’s “lower bound” has suddenly become its “best guess.”

After weeks of haggling with House Republican leaders, Senate Democrats struck a deal during last year’s legislative session to scale back the manufacturing sales tax exemption. According to staff analysis from March 2016, the new code language was expected to reduce state revenues by only $22 million during fiscal year 2017, instead of the $35 million the Department of Revenue had projected.

I am seeking further information on how much the new exemption for manufacturers contributed to what Underwood called “perplexing” sales tax numbers.

My hunch is that Muller was correct a year and a half ago: state officials lowballed the cost estimate for a Branstad administration priority.

Iowa lawmakers from both parties have rightly called for more scrutiny of tax credits and exemptions. For such efforts to be worthwhile, we need staff to use sound methodology when evaluating the impact of tax breaks on state revenues.

3. How much did the slump in the agricultural sector contribute to the shortfall?

A budget way out of balance creates an awkward problem for Iowa Republican politicians who have long postured as “fiscally responsible,” even as they spent more than the state was taking in.

Months ago, Branstad and other GOP officials settled on a convenient scapegoat: the farm economy.

The governor declared in his Condition of the State address in January, “Although we have faced a headwind out of Washington, D.C., that is stifling our agricultural economy, we still have positive state revenue growth.”

Lieutenant Governor Kim Reynolds echoed the talking points during a January appearance on Dave Price’s WHO-TV show (starting around the 3:20 mark).

So, you know, I think, if you look at it, our projections were conservative, but you know, with farm prices and commodities where they’re at, that’s had an impact on this state. The federal EPA [Environmental Protection Agency] hasn’t been a partner, I mean, that’s been a detriment, really, and ethanol, and again, farm prices, and so, the reality is, we needed to–they met in December, we needed to balance the budget, it was out of balance.

In February, Branstad and Reynolds blamed “the downturn in our agricultural economy” when the governor signed into law the third-smallest increase in K-12 school funding in four decades.

Yesterday’s statement from the governor’s office asserted, “Our Iowa economy is growing. But the challenging farm economy, with commodity prices below the cost of production for far too long, has hit our state revenues.”

Senate Majority Leader Dix joined the chorus:

Overall, Iowa’s economy is headed in a positive direction. However, with the price of corn, beans and other commodities continuing to remain below the cost of production for Iowa farmers, our state revenues have lagged.

I am reaching out to analysts with better skills for fact-checking those claims.

A small percentage of Iowans are directly engaged in farming. Intuitively, their challenges seem unlikely to be the primary reason income tax revenues fell so far below projections. As Swenson explained above, the personal income tax numbers built into the 2017 budget were never grounded in reality–even for years when corn and beans commanded much higher prices.

Farm commodity prices also seem like an improbable culprit for sales tax receipts not meeting projections.

Any relevant comments are welcome in this thread.

3 Comments

Ultimate objective

While I think the basic fault for this is the $500 million of tax credits and corporate giveaways that come out of the budget, I am not sure that this administration does not love the idea of using this excuse to fire even more state employees and essentially destroy the administrative ‘state’ in the state of Iowa.

gmcgdem Wed 15 Mar 6:31 PM

Whuh, the EPA?

I realize that hauling out the big bad EPA for blaming and shaming, per above, is standard Republican practice now. But I genuinely don’t understand what the blaming is for in this case. Nonpoint ag pollution is unregulated, so farmers can and do externalize the costs of sending soil and nutrients downstream. CAFOs are regulated, but not much. Ethanol is mentioned separately.

So apart from ethanol battles, how is the EPA to blame? The EPA generously signed off on the gutless wonder known as the Iowa Nutrient Reduction Strategy, thereby letting Iowa get away with doing essentially nothing about dirty water for the foreseeable future. How much more of a partner does Reynolds expect the EPA to be?

PrairieFan Thu 16 Mar 1:20 AM

it's just word salad

A bunch of talking points strung together in a way Reynolds hoped WHO-TV viewers would find convincing.

Obviously EPA policy on ethanol or anything else has minimum effect on Iowa’s tax revenues.

desmoinesdem Thu 16 Mar 8:43 PM