Dan Piller was a business reporter for more than four decades, working for the Des Moines Register and the Fort Worth Star-Telegram. He covered the oil and gas industry while in Texas and was the Register’s agriculture reporter before his retirement in 2013. He lives in Ankeny.

The pending end of Iowa’s first-in-the-nation caucuses will no doubt set off long nights of reminiscences covering a half-century among the state’s political/media intelligentsia. But I will step forward with a claim that is not to be challenged.

I was the first-in-the-nation critic of the Iowa caucuses. It happened entirely by accident.

On the night of January 24, 1972, I was an extremely junior member of the Des Moines Register staff and assigned to struggle through a blizzard to Democratic Party headquarters, then located in the dingy upstairs of the old Shops Building on Walnut St., to get the results of the first Iowa presidential caucus.

This historic honor fell on me because Jim “The General” Flansburg, the Register’s chief political reporter, earned his nickname by staying at headquarters on big stories and directing minions out in the field.

Until Flansburg briefed me, I was unaware the caucuses were even happening. There had been very little advance news coverage or campaigning, and the Iowa Poll hadn’t bothered to sample opinion. No other reporters were assigned to the story and there were no photo assignments. All Flansburg wanted was the final totals, and he conveyed no sense that history was about to be made.

Sulking at what I thought was a demeaning errand crammed down to a vulnerable junior staffer, I trudged through snowdrifts to the Shops Building. When I reached the second-floor party headquarters, I was astonished to behold several of the nation’s most eminent political reporters, such as Johnny Apple of the New York Times, David Broder of the Washington Post, Jack Germond of Gannett, Jules Witcover of the Los Angeles Times and Bruce Morton of CBS. They were drinking beer out of cans and amusing themselves with stories about Lyndon Johnson, whom they all covered and still considered a legend.

Neither of the leading presidential candidates, Senators Ed Muskie of Maine and George McGovern of South Dakota, appeared anywhere in Iowa that night. But McGovern’s campaign manager, a dapper fellow named Gary Hart, was present. There wasn’t a single female in the room, so I didn’t get to see Hart put on the kind of charm that a decade and a half later undid his presidential campaign on the Monkey Business.

Nobody had the slightest idea what was going to happen and, as it turned out, nothing did. The blizzard wiped out most of the caucuses, so when deadline hour arrived I had to report to Flansburg that there were no results. He was renowned for his cyclonic rages, but on that night, he chuckled and said, “I thought that might happen.”

So, I made my way back to the Register through snowdrifts, which had grown higher while I had wasted my time at the Shops Building, each step enlarging my grudge against the caucuses.

It took three days for Iowa to dig out of the snow, conduct the caucuses, and tabulate the results. “Uncommitted” received 35.8 percent, Muskie nearly tied with 35.5 per cent of the vote and McGovern received 22.6 percent.

McGovern’s defeat in a neighboring state at the hands of a guy from Maine should have been cause for him to bag his head. Instead, Gary Hart somehow spun the unexpected McGovern total into a “victory,” which took McGovern all the way to the nomination. When McGovern lost 49 states that November to the unindicted co-conspirator, Richard Nixon, I recalled that unimpressive caucus experience and assumed that the Democrats would have the good sense to tell Iowa and its caucuses to get lost.

But the caucuses turned out to be the thing that wouldn’t die.

Flansburg assigned me another errand in 1975. I journeyed to Prairie City to hear a presidential candidate named Jimmy Carter, of whom I had never heard. It was a pleasant spring day and the corn was just beginning to emerge, so I was in a reasonably positive mood as I found the Carter gathering of about a dozen people in a private residence.

The former governor of Georgia had a less-than-forceful personality, which probably was useful in the post-Watergate world. The problem was his thick Georgia accent, which was virtually unintelligible to my Midwestern ears. I found a Carter aide to translate Carter’s message; a solemn promise to never tell a lie. I filed a brief story and then reported to Flansburg that since Jimmy Carter was unable to stir a living room crowd in Jasper County, Iowa, he was unlikely to arouse the multitudes at a national convention.

(My opinion of Carter didn’t improve when I learned later than the same Carter underling who provided a copy of the candidate’s talk had made moves, unsuccessfully, on my then-girlfriend.)

So, when the 1976 caucuses were held the following February, I wasn’t surprised to see that Carter had finished second to “uncommitted.” Forgetting the McGovern precedent four years earlier, I figured Carter would be headed back to the land of peach pits. Instead, he became the front-runner, made his way to the nomination and then, to my even greater bewilderment, the White House. Carter’s subsequent fumblings in the Oval Office were less of a surprise when I recalled his tepid performance that day in Prairie City.

My inability to see political greatness in George McGovern and Jimmy Carter caused me to revise my professional ambitions, from political reporting to the much more logical world of business and financial journalism.

I was thus more a bemused observer in 1980, when the Iowa caucuses, with its certified first-in-the-nation status firmly in place, attracted a star-studded constellation of political and media heavies. Walter Cronkite and John Chancellor, the reigning anchor/kings of the network television news that dominated in those pre-CNN days, honored Des Moines with their presence. Such was the power of the media stars that the Iowa Democratic Party set up a viewing area where visitors, for a fee, could watch the mix of television, print and radio stars in the manner of patrons at a zoo.

Among candidates the greatest grandee in 1980 was Senator Ted Kennedy, who conducted what turned out to be a Last Hurrah for the New Frontier on Iowa’s frozen soil. I actually bumped into Joseph Kennedy II coming out of a Court Avenue pawn shop (a surprise to me, since the Kennedys were so rich), but those gelid days in early 1980 were heady indeed.

Cronkite and Chancellor did their caucus duties before adoring masses in 1980, and Carter easily put away poor Ted Kennedy, still dogged by Chappaquiddick. George H.W. Bush won the Republican caucus, a surprise win over Ronald Reagan, whose personal memories of Iowa winters caused him to sensibly sit out the caucuses in Malibu.

Caucus night in 1980 provided an unexpected treat for me: a conversation with perennial presidential candidate Harold Stassen who was doing double duty as correspondent for a radio network. Stassen was a figure of ridicule in 1980, but in the late 1940s he was a major power in the Republican Party, so much so that he commanded an audience with Josef Stalin on a trip to Moscow in 1947. His reminiscences of the chat-up with the Soviet dictator helped pass the time before George Bush came into the Fort Des Moines Hotel ballroom to claim his victory.

Bush’s momentum from Iowa turned out to be short-lived. Reagan’s presidency and his revolution happened anyway. By this time, I had given up on the idea that the political parties would draw the obvious conclusion that the Iowa caucuses were a poor way to start the nomination process.

I had relocated to Dallas by 1984, and when the caucus frenzy erupted, I found myself in the unexpected position of defending my former state and its peculiar political tradition. The rest of the world, I learned, was less-than-charmed by the Iowa caucuses.

How, I was asked repeatedly, did flyover, white bread Iowa get off thinking that it should play such an over-large role in steering the nomination process? I replied that Iowans were smart folks, citing the old statistic that Iowa had the highest literacy rate in the nation. The reply to that was along the lines of “if Iowans are so damned smart, why don’t they have the good sense to get out of the snow?”

That hot national spotlight so coveted by Iowans wasn’t warm enough to warm Iowa’s snow. The state’s winter weather, not its politics, dominated most of the reactions from my new Sunbelt friends. I was asked numerous times if I had one of those floppy-earned, fur lined snow hats that seemed to be the uniform (at least on TV) of Iowa caucus goers. Couldn’t the TV reporters find someplace else for their stand-ups besides a farm field or the plaza in front of the state capitol, their lower extremities covered by a foot or more of snow and their faces obscured by breath vapor?

Through subsequent years, those questions had no easy answers. Even the beautiful Iowa summertime cinema images in “Field of Dreams” and “Bridges of Madison County” couldn’t crack the stereotypes about Iowa’s weather. When the expanded Big 8 Conference took in the Texas universities as members of the new Big 12 Conference in the 1990s, memories of snow-driven caucus coverage caused extended panic among Texans dreading semi-annual treks to a land most of them had been conditioned to think of an American version of Siberia.

I deduced that for all their earnestness, Iowans weren’t doing the image of their state much good by dragging the entire political and media establishment to the state during its worst period of weather, for a process that few understood or admired. My early, self-interested dislike of the caucuses morphed into a wish and hope that Iowans could see their way to voluntarily giving up the state’s first-in-the-nation status.

When I returned to the Des Moines Register in 2007, I sensed a desperation to end a dry spell from its last Pulitzer Prize. No problem, I confidently suggested. Simply editorialize in favor of ending the caucuses and grateful nation would probably bestow not merely a Pulitzer, but perhaps an Oscar, Emmy, and maybe even a Peoples’ Choice Award. But it never happened. Iowa’s political/media establishment barricaded itself behind barriers of remote TV vans and grimly held on until the inevitable.

So now, like a child whose favorite toy was taken away by no-fun grownups, Iowa Democrats will be left to sulk and warm themselves with memories of prune Danish and coffee, consultants and anchormen, straw polls and invitations to the White House for lucky Iowans who helped the current occupant get there.

As the first-in-the-nation caucus critic, I should be jumping for joy. Instead, I feel an empty sadness on behalf of my Iowa friends, who for decades found sincere happiness putting their snowy home on display on behalf of democracy.

As an old friend told me on my return to Iowa, “oh, I know the caucuses aren’t perfect. But they’re so darn much fun!”

I never heard a better explanation.

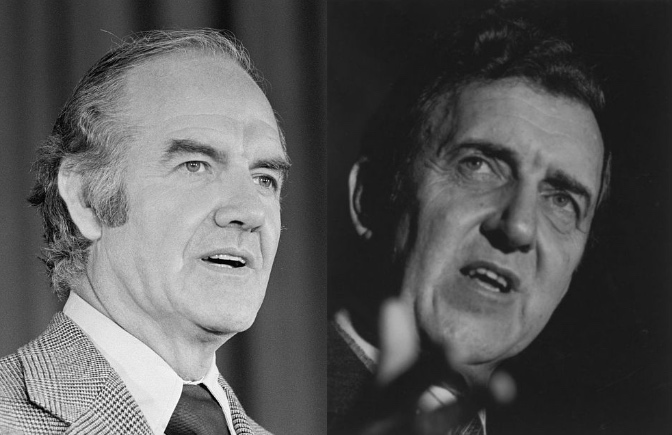

Top image: George McGovern (left) and Edmund Muskie (right) in pictures from 1972. “Uncommitted” finished first in the 1972 Iowa caucuses, followed by Muskie and McGovern. Warren K. Leffler photographed McGovern in this picture available through the Library of Congress. The photograph of Muskie comes from the U.S. Senate Historical Office.

3 Comments

These are good stories, thank you, Dan Piller

When I attended the 2020 caucus, the travel weather was cold rain. A family arrived in the small caucus room about two thirds of the way through the process, looking cold and wet, apparently a mom, dad, and two little kids. They apologized for being late and managed to find (uncomfortable) seats and I overheard a whisper about babysitting problems.

That was the last caucus straw for me. I already knew Iowa’s system was a huge problem for many Iowans, and seeing that young family made me decide that if the system wasn’t transformed, I was through with caucusing for good. Laura Belin’s 12/4 post is absolutely right. The system should have been revamped long ago.

PrairieFan Mon 5 Dec 12:51 PM

All of ‘em

I don’t remember snow in Keokuk in 1972, but Keokuk should be in Missouri and maybe is by now.

✔️I shared an elevator at the Savory in 1988

✔️Same year I stood next to Paul Simon at a urial in that hotel between 2nd and 3rd just South of 235. Not the singer.

✔️I got a personal phone call from Mo Udall in 1976

✔️… to be continued

iowagerry Mon 5 Dec 1:03 PM

Well done. Thanks

A long time age my wife was head of our precinct and to avoid having to hire a babysitter we had the caucus in our living room. To get people to represent us at the county convention my wife called neighbors to see if they were willing to attend. At that time nobody paid any attention to the Iowa caucus. Why should they?

jsneff-1964 Tue 6 Dec 11:23 AM