Douglas Burns is a fourth-generation Iowa journalist. He is the co-founder of the Western Iowa Journalism Foundation and a member of the Iowa Writers’ Collaborative, where this article first appeared on The Iowa Mercury newsletter. His family operated the Carroll Times Herald for 93 years in Carroll, Iowa where Burns resides.

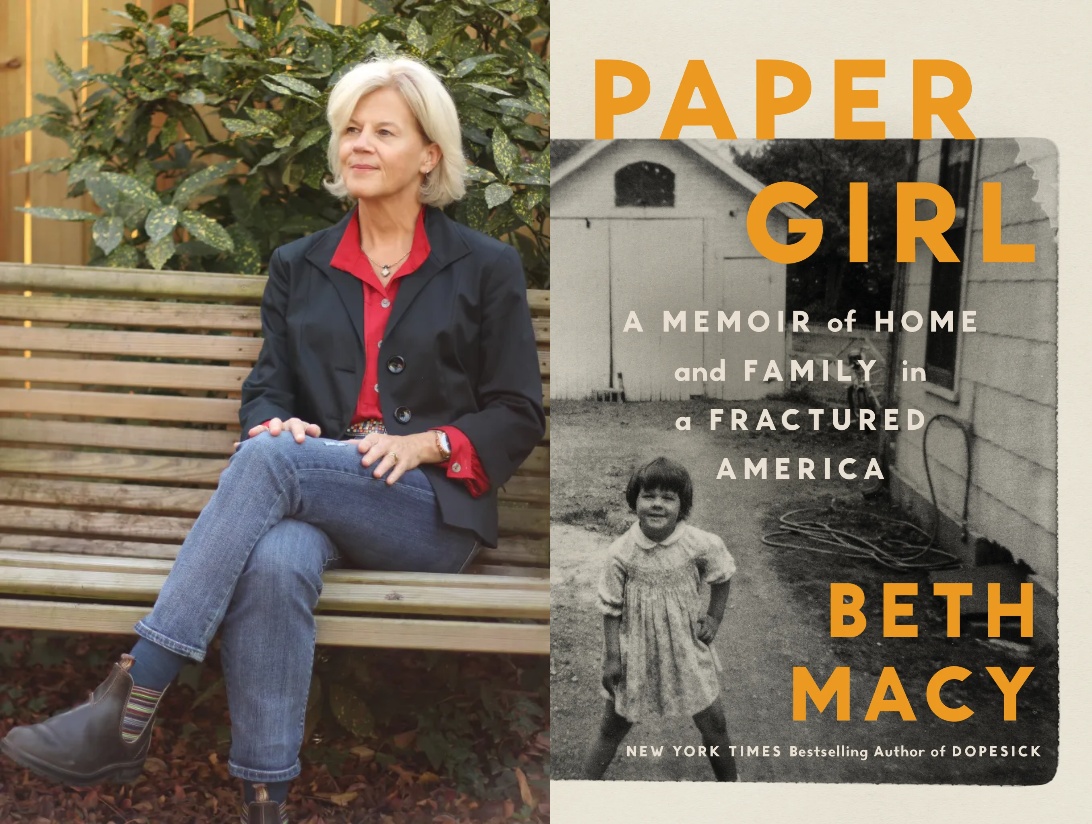

Through what political scientists might call a deep canvass into her own culturally polarized family in rural, de-industrialized Ohio author Beth Macy gives us a riveting, devastating and call-to-action mirror into our nation with her extraordinary new book, Paper Girl: A Memoir Of Home And Family In a Fractured America.

The powerhouse work of non-fiction connects three threads—Macy’s memoir of life in rural Ohio, both as a kid and returning adult, exhaustive and exhilarating reporting on a changing America, and a fierce case for the role of local news in preserving or stitching back democracy.

You can get a first-hand preview of Paper Girl in Des Moines, Iowa this weekend with the author of the just-released book.

Macy will talk about Paper Girl—she delivered newspapers before writing for them—and her award-winning career as a journalist as a featured speaker at Beaverdale Books’ third-annual Banned Books Festival in Des Moines. I’ll moderate the conversation with Macy beginning at 2:30 p.m. this Saturday, October 11, at the Franklin Event Center, 4801 Franklin Avenue.

The event is free and open to the public.

Macy will hold a book signing following the dialogue on the stage in the auditorium.

The full festival runs from noon to 5 p.m.

Macy, who grew up hardscrabble, but with the now-disappearing middle-class ethos that sustained her beloved hometown of Urbana, Ohio, is the author of Dopesick, a defining book on the opioid crisis that’s whipsawed through rural America. Hulu picked up and adapted the book for its popular series of the same name, starring Michael Keaton and Rosario Dawson.

A former long-time reporter with the scrappy and estimable Roanoke Times in Virginia, where she had the families beat, Macy brings rural reason and passion to her new work. In Paper Girl, she seeks to reconcile the Ohio town of her youth in the 1970s and 1980s, a challenged place economically, but one with generally shared-and-accepted-facts sensibility, with the circus, shake-the-sand-from-your-eyes tribalism that pervades her home state, hometown—and many of her family and childhood friends.

“For generations, women in our family suffered from the burdens of addiction, poverty, and what I now see as the broken masculinity of their men, though we never had such an elevated term for it; it was just what we knew,” Macy writes.

Macy does the searingly hard work here. She talks for hours with siblings who have arrived at a vastly different worldview than hers. She plumbs into the reasons and family fallout of loved ones veering into the Trump cult—to the point where they view her profession, journalism, fact checking, the one in which Macy’s reached the pinnacle, as un-American, the source of their own pathos.

More than half of Americans, 54 percent, believe another civil war is coming, Macy reports in the book.

Are the culture wars “growing pains” on the way to a more equitable multi-racial America, or is the nation headed to a second Civil War? Macy asks.

“I ask myself that question every day,” Johns Hopkins political scientist Lilliana Mason tells Macy.

Also concerning: 81 percent of local officials nationwide (many in volunteer roles on school boards and modest paying small-town councils) reported experiencing political violence and threats and harassment, according to a 2021 National League of Cities study Macy cites in Paper Girl.

“There’s no longer a shared purpose behind ‘We the people,’” the Pulitzer Prize-winning historian Taylor Branch tells Macy in the book. “Instead, people convince themselves that their liberty depends on taking a gun to a Starbucks.”

Through one uncomfortable conversation after another, Macy, who backgrounds the exchanges with soaring and poignant home-and-hearth memories and brutal, painful accounts of abuse and addiction, begins to get at this most American of questions: how did we get to this place of such discord and distrust, and can we get out of it?

We are along for the ride as Macy starts with her own family—and an ex-boyfriend who went from being a liberal young man to one of the leaders of the hate peddling against Haitian immigrants in Springfield, Ohio before the 2024 election. The hours-long dinner she has the with former beau is as as excruciating to read as it is revelatory. Macy talks to the ex for three hours in a restaurant—hearing wild conspiracy theories, and even having to wait as he steps outside for cigarette breaks. You want her to scram from the dinner, and then, you don’t want it to end.

Her high school class reunion planning falls into the madness of the moment with organizers provoking and scolding each other over politics.

Other civic unrest and strained relationships factor into her hometown’s current identity and Macy’s book. Her interviewing style is at once ferocious and kind, and the narrative leads us to frightening places.

It’s not hard to see how Urbana, Ohio, near Springfield and west of Columbus, a prominent stop on the Underground Railroad for runaway slaves before the Civil War, could be a flash point in a second civil war.

But Macy provides hope, a restless optimism.

She celebrates the buoying impact of educators and makes the case for stronger public education, the teachers who lifted Macy, the paper girl from an economically challenged family, into a college-bound student who would go on to the be one of the nation’s top journalists—and a reporter with roots and a rare understanding of rural America. At its core, that’s why this book demands to be read. Nobody gets rural America, its past, present, the charms and stains, like Beth Macy. I’ve had the opportunity to travel on a reporting project on rural economic development with her in Virginia, where she lives now with her husband. I know rural America. I know Beth Macy’s reporting. They match.

I’m quoted in Macy’s book on rural journalism and the essential role of community newspapers, what I often refer to as the last bastion of collective reality, and the destruction of truth itself by social media companies.

Fact: President Donald Trump won 91 percent of the counties in the United States without a source of professional local news. Macy reports.

If there is, indeed, a way back from the fact-less, senseless and increasingly dangerous political divide, the cliff’s edge of chaos and widespread violence, Beth Macy’s book is a road map showing us a route, faint as it might be on the atlas and in our aspirations, for a possible return to a destination of civic sensibleness, shared-truths debates and good-faith discourse.

As she shows with her own family, there are a lot of hard, really hard conversations on that journey.

4 Comments

A Great Article

There’s a wonderful article by Beth Macy related to this book in The Atlantic titled What Happened to Ohio. I recommend it.

Bill Bumgarner Thu 9 Oct 1:06 PM

her work is great and appreciate people sharing it in Iowa

but there never was a ” destination of civic sensibleness, shared-truths debates and good-faith discourse” to go back to. Books like hers may help to start building a better future but only if Democrats don’t make the mistake Biden and company did of trying to go back to the same institutions/norms that led us to where we are now. As Elie notes here in relation to the courts we are desperately in need of a platform for radical changes to our ways of governance:

https://www.c-span.org/program/washington-journal/elie-mystal-on-comey-indictment-and-trump-justice-department/666409

dirkiniowacity Thu 9 Oct 1:24 PM

Wow, Douglas Burns...

…I’ve read other essays by you on BH, but I don’t think I’ve ever read a better one.

PrairieFan Thu 9 Oct 1:24 PM

dirkiniowacity

I am a senior who has done political work over the decades, and asking me to believe that the civic-sensibleness situation was never better than it is now is asking me to believe that at least three decades of my lived experience were illusions. I’ll need far, far better evidence before I believe that.

PrairieFan Thu 9 Oct 4:01 PM