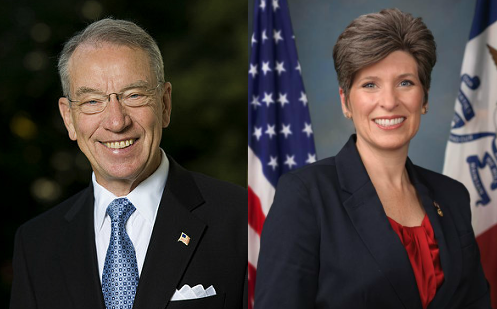

Iowa’s senior Senator Chuck Grassley will become the president pro tempore of the U.S. Senate when Congress reconvenes in January, and junior Senator Joni Ernst will join the Republican leadership team for the first time.

For more than a century, the senator from the majority party with the longest tenure has served as president pro tempore. Most recently, Senator Orrin Hatch held the position, but he is retiring. The U.S. Constitution names the president pro tempore as one of the Senate officers, assigned the role of presiding over the chamber when the vice president is not present. Grassley won’t be holding the gavel most of the time, however; that role typically rotates among members of the majority caucus.

Under federal law, Grassley will be third in line to serve as acting president if the current president, vice president, and speaker of the House of Representatives were all killed or incapacitated. I enclose below a news release from Grassley’s office, with more information about the president pro tempore’s role.

In her fifth year as a senator, Ernst moves into the fifth-ranking leadership position, Senate Republican Conference vice chair. Burgess Everett reported for Politico that Senator Deb Fischer of Nebraska also sought that position, making it “the only contested leadership race.”

Ernst’s win over Fischer marks the first time in eight years a woman is in the Senate GOP leadership. Senators said they were not provided with a vote total, and Fischer quickly moved on and told reporters she’s going to continue to be “very active” in the caucus’ work. Ernst, who is up for reelection in 2020 and is expected to face a credible Democratic challenge, said she will focus on sharing the GOP’s record of “prosperity” with her constituents while in Washington.

Alexander Bolton reported for The Hill that today’s vote followed “months of quiet campaigning in the conference.”

Senate Republicans saw Ernst as someone who might be a better communicator for the conference on television, while Fischer garnered praise as someone who worked diligently behind the scenes to build relationships with members of GOP leadership.

Ernst posted on her Twitter feed,

I want to thank my colleagues for the tremendous opportunity to represent them in leadership. The Senate Republican conference is strong and will only get better the more we work together (1/2).

— Joni Ernst (@SenJoniErnst) November 14, 2018

I seek to serve as a strong voice in leadership, while bringing new ideas & a fresh face to the team.Whether I am fighting for our servicemembers & our country’s global interests, or finding solutions to rural America’s challenges–I seek to make Iowans & all Americans proud(2/2).

— Joni Ernst (@SenJoniErnst) November 14, 2018

Having a leadership role will be a talking point for Ernst in her 2020 campaign and will increase her visibility in the national media. Iowa’s seat may not be among the most vulnerable of the 21 Senate seats the GOP will be defending next cycle, but some Democrats feel encouraged about the party’s prospects against Ernst after Cindy Axne and Abby Finkenauer took out well-funded Republican incumbents this year.

One downside to being in leadership: it guarantees that Ernst will continue being a rubber-stamp for anything and everything GOP leaders want. She won’t be able to brag about standing up for Iowans against her own party when necessary.

Speaking of which, don’t expect Iowa’s senators to provide any meaningful check on President Donald Trump. They welcomed his illegal and unconstitutional appointment of Iowan Matt Whitaker as acting attorney general last week. Whitaker is widely seen as a hatchet man picked to bury special counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation, but Ernst isn’t worried. Brianne Pfannenstiel covered the senator’s November 9 town-hall meeting in Ames,

Asked by an attendee if she would “stand up to the president” if Whitaker or others move to wind down Mueller’s investigation, Ernst replied, “I don’t think that’s going to happen. I don’t.”

“I don’t know that the investigation itself needs to be protected,” Ernst said. “We’ve gone two years with a very thorough investigation. … Two years of investigations have absolutely nothing to show for it.”

Members of the audience pushed back, pointing out that Mueller’s team has handed down more than 100 criminal counts against more than two dozen people.

Ernst maintained that the investigation should not be allowed to continue in perpetuity, but she declined to say at what point it should be cut off.

As chair of the Senate Judiciary Committee, Grassley could rally his colleagues to oppose Trump’s end-run around the Senate’s confirmation power. (Committee members would have standing to challenge Whitaker’s appointment in court.) But Grassley doesn’t even intend to hold a hearing on the matter, he told Iowa reporters on November 14. Nor does he think Whitaker needs to recuse himself, despite his sharp criticism of Mueller’s investigation and his connections to Sam Clovis, a former Trump campaign adviser who has been interviewed regarding possible Russian interference. In Grassley’s view,

“There`s been no talk from the president of the United States anymore about witch-hunts, about replacing Mueller,” said Grassley. “In fact, he said just the opposite; that he has no prospects of firing Mueller, and so Whitaker, being appointed by the president of the United States, wouldn’t dare do something contrary to what the president wants done.”

UPDATE: Grassley addressed Whitaker’s appointment as part of his prepared remarks for a November 15 Senate Judiciary Committee executive business meeting.

Turning to another topic, I want to address some complaints I’ve received from the other side about President Trump’s decision to appoint Matthew Whitaker as Acting Attorney General. After all the withering criticism lodged against former Attorney General Jeff Sessions over the past two years, it’s incredibly ironic that members are now distraught over former Attorney General Sessions’ resignation last week.

As far as the appointment of Matthew Whitaker, the Federal Vacancies Reform Act gives the President the authority to direct a senior official within DOJ to serve as the acting officer as long as that senior official served at the agency for at least 90 days prior to the appointment. The Vacancies Act works in tandem, and is not inconsistent with, the statute addressing DOJ vacancies. DOJ’s Office of Legal Counsel has now issued three separate legal opinions – in 2003, 2007, and yesterday – confirming that the President can fill vacancies of Senate-confirmed agency heads under the Vacancies Act. In other words, President Trump acted in strict conformance with the law; and Acting Attorney General Whitaker’s appointment is perfectly legal. I have confidence that Acting Attorney General Whitaker will carry out the functions of the Justice Department to the best of his abilities.

In the meantime, I look forward to working with the President on the confirmation effort for whomever the President nominates. And although I will welcome a new nominee, the Senate is never a rubber stamp for any president, and won’t be for this President or his nominee. We will perform our advice and consent role and properly vet whomever the President chooses to be the next Attorney General.

Conservative legal scholars including John Yoo, deputy assistant attorney general under President George W. Bush, disagree with Grassley’s reading of the law. Yoo wrote in The Atlantic,

When a senior government official resigns, dies, or cannot do his or her job, the Federal Vacancies Reform Act allows the president to appoint another official of the same federal agency “to perform the functions and duties of the vacant office temporarily in an acting capacity.” Whitaker’s appointment clearly meets the terms of the congressional statute.

But Whitaker’s appointment must still conform to a higher law: the Constitution. As the Supreme Court observed as recently as this year, Article II provides the exclusive method for the appointment of “Officers of the United States.” The president “shall nominate, and by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, shall appoint Ambassadors, other public Ministers and Consuls, Judges of the Supreme Court, and all other Officers of the United States.” The appointments clause further allows that “the Congress may by Law vest the Appointment of such inferior Officers, as they think proper, in the President alone, in the courts of law, or in the heads of departments.”

The Constitution, therefore, recognizes only two types of federal officers. First, there are what the Supreme Court has come to recognize as “principal” officers, who require presidential appointment with Senate advice and consent. Second, there are “inferior” officers, posts for which Congress can choose to allow appointment by the president, courts, or even Cabinet members alone. As the nation’s top lawyer, the attorney general heads one of the four “great” departments of government, along with State, Defense, and Treasury, and the office has existed since the first Washington administration. The attorney general is clearly a principal officer of the government; if he or she is not, it is difficult to imagine what other officer is—the Supreme Court said as much in Morrison v. Olson, the 1988 case upholding the constitutionality of the independent counsel as an inferior officer because she reported to the attorney general as the principal officer.

Whitaker’s appointment violates the appointments clause’s clear text because he serves as attorney general, even if in an acting capacity, but never underwent Senate advice and consent.

November 14 press release from Senator Chuck Grassley:

Grassley Set to Become Senate Pro Tempore for 116th Congress

Nov 14, 2018

WASHINGTON – Today the Senate Republican majority of the upcoming 116th Congress unanimously nominated Sen. Chuck Grassley of Iowa, who was first elected to serve Iowans in the U.S. Senate in 1980, to be Senate pro tempore, a position that has historically been bestowed upon the most senior member of the majority party in the upper chamber of Congress. Upon his expected election to the position by the full Senate on January 3, 2019, Grassley will become third in the line of presidential succession following the Vice President and the Speaker of the House of Representatives.Grassley has represented Iowa in the U.S. Senate for 38 years. Grassley will succeed Sen. Orrin Hatch of Utah as Senate pro tempore. The only other Iowan to hold the office was Sen. Albert B. Cummins, who was first chosen in 1919, 100 years before Grassley is set to assume the role early next year. Cummins served as Senate pro tempore in the 66th, 67th, 68th and 69th Congresses.

“This is an honor for me and the state of Iowa. The President pro tempore is one of a handful of offices specifically named by the Founders in the Constitution,” Grassley said. “I may only be three heartbeats away from the Oval Office, but my heart is and always will be in Iowa and here in the U.S. Senate, where I’ve worked for the people of Iowa and our nation for 38 years. My commitment to representative government and the deliberative body of the U.S. Senate is stronger than ever. I’ll work to see that we uphold the Senate as a check on the executive and judicial branches of government, including our constitutional authority to provide advice and consent.”

Information from the Congressional Research Service regarding the position of Senate pro tempore can be found below:

The U.S. Constitution establishes the office of the President pro tempore of the Senate to preside over the Senate in the Vice President’s absence. Since 1947, the President pro tempore has stood third in line to succeed to the presidency after the Vice President and the Speaker of the House.

Ninety different Senators have served as President pro tempore.

Since 1890, the President pro tempore has customarily been the majority party Senator with the longest continuous service.

The President pro tempore of the Senate is one of only three legislative officers established by the U.S. Constitution. The other two are the Speaker of the House of Representatives and the Vice President of the United States, who also serves as President of the Senate. The Constitution designates the President pro tempore to serve in the Vice President’s absence. The President pro tempore is often popularly known as the President pro tem.

With the passage of the Presidential Succession Act of 1947, the President pro tempore was restored to the line of succession, this time following the Vice President and the Speaker of the House.

Article I, Section 3, of the U.S. Constitution declares, “The Senate shall choose their other Officers, and also a President pro tempore in the Absence of the Vice President, or when he shall exercise the Office of President of the United States.” Aside from the Vice President’s designation as President of the Senate, the President pro tempore is the only position in the Senate explicitly established by the Constitution.

Under the Constitution, the Vice President may cast a vote in the Senate only when the body is equally divided. The question of whether a President pro tempore retained his vote while he was performing the duties of his office was clarified by a Senate resolution adopted on April 19, 1792, which declared that he retained “his right to vote upon all questions.”

In the modern Senate, with the exception of his authority to appoint other Senators to preside, the President pro tempore’s powers as presiding officer differ little from those of the Vice President or any other Senator who presides over the Senate. These powers include the authority to:

Recognize Senators desiring to speak, introduce bills, or offer amendments and motions to bills being debated. The presiding officer’s power of recognition is much more limited than that of the House Speaker or whoever presides in the House. In the Senate, the presiding officer is required by Rule XIX to recognize the first Senator standing and seeking recognition. By precedent, the party floor leaders and committee managers are given priority in recognition.

Decide points of order, subject to appeal by the full Senate.

Appoint Senators to House-Senate conference committees, although this function is essentially ministerial. Conferees are almost always first determined by the chairman and ranking Member of the standing committee with jurisdiction over the measure, in consultation with party leaders. A list of the recommended appointments is then provided to the chair.

Enforce decorum.

Administer oaths.

Appoint members to special committees—again, after the majority and minority leaders make initial determinations.

Over the years, other powers have also accrued to the President pro tempore. Many of these are ministerial. Decisions are first made by each party’s principal political leaders—in the Senate, the majority and minority floor leaders—and the President pro tempore’s charge is to implement their decisions. These include appointments to the following positions:Director of the Congressional Budget Office (made jointly with the Speaker of the House);

Senate legislative counsel and legal counsel;

Senators to serve on trade delegations; and

Certain commissions, advisory boards, and committees, such as the boards of visitors to the U.S. military academies, the American Folklife Center, and the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Council.

The President pro tempore is responsible for recommending candidates for U.S. Comptroller General, the head of the Government Accountability Office.

After the President has submitted a report pursuant to the War Powers Act, the President pro tempore and the Speaker of the House have the authority to request jointly that the President convene Congress in order to consider the content of the report and to take appropriate action.

[The] President pro tempore works with the Secretary of the Senate and the Sergeant at Arms of the Senate to ensure the enforcement of the rules governing the use of the Capitol and the Senate office buildings.

Senator Robert C. Byrd of West Virginia, who served as President pro tempore four times, noted that “Because the president pro tempore stands in the line of presidential succession, he is given a direct-access telephone to the White House and would receive special evacuation assistance from Washington in the case of national emergency.”

The President pro tempore is also provided with a personal security detail by the U.S. Capitol Police.