Chris Jones is a research engineer (IIHR-Hydroscience and Engineering) at the University of Iowa. First published on the author’s blog. -promoted by Laura Belin

Iowa has around 3 million people, a total that has changed little over the last 80 to 90 years. People are large animals, and as such our bodies produce a lot of waste. That being said, we produce much less waste than the animals that we eat.

Take hogs, for example. A feeder pig is about the same size as a human being, but it excretes 3 times as much nitrogen (N), 5 times as much phosphorus (P), and 3.5 times as much solid matter (TS-total solids) (1). Some of this is because of the pig’s diet and some it is because modern hogs grow really, really fast (these things relate to each other, obviously). A pig weighs about 3 pounds at birth and about 250 pounds at slaughter a mere 6 months later, so it is gaining more than one pound per day.

By comparison, a human infant gains a pound about every 20 days. There’s a reason we use the word “hog” metaphorically and pejoratively because they consume anything and everything in sight virtually non-stop, which is one reason why they make for a good food animal.

Everybody knows Iowa has a lot of livestock. If you’re like me, maybe you have heard from time to time that our state has enough animals to effectively be as populous as California, using one common example. As you will soon see, it’s bigger than that. Much bigger.

Exactly how many of each species that we have at any one time is a difficult thing to quantify for reasons I will not get into here. I’m going to present some watershed-by-watershed numbers for the following analysis and I do not claim that they are exact, but I have consulted with a couple of experts and I am confident they are in the ballpark.

Statewide, we have around 20-24 million hogs; 250,000 dairy cattle; 1.8 million beef cattle, 80 million laying chickens, and 4.7 million turkeys. I did not consider sheep, goats, horses or broiler chickens.

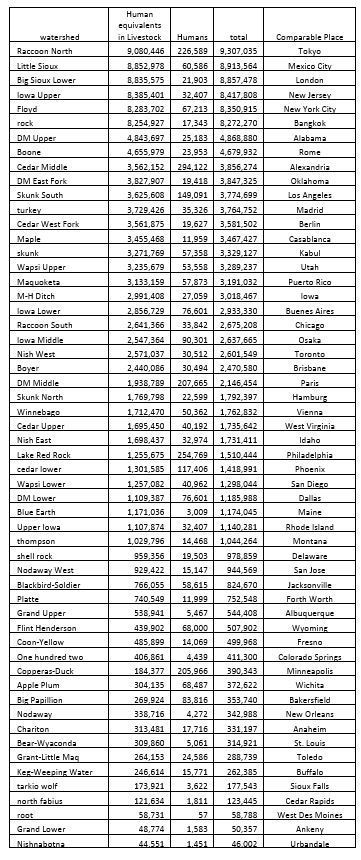

When I apply the N, P and TS values of the waste from these animals, what would be the equivalent-sized human population that would generate such waste is staggering:

In total, these five species generate the waste equivalent to that produced by about 134 million people, which would place Iowa as the 10th most populous country in the world, right below Russia and right above Mexico. (Caveat: obviously Russia and Mexico have their own livestock that I am not counting.) And in terms of population density in the context of N, P and TS waste, Iowa would come close to the country of Bangladesh.

Managing the waste from these animals is possibly our state’s most challenging environmental problem. Of course we have a lot of cropland to apply this waste, but the time windows in which farmers have to do this in without damaging the crops with equipment are usually not large. Wet, cold and hot weather can all limit application. As a result, there are only a precious few weeks in a year when this Mt. Everest of waste can be applied to corn and soybean fields.

And there can be no doubt that the sheer amount, and the logistical complications of hauling and handling it, have consequences for water quality (2). Watersheds with the highest density of livestock frequently have some of the highest stream nitrate concentrations (North Raccoon, Floyd, and Rock River watersheds, for example).

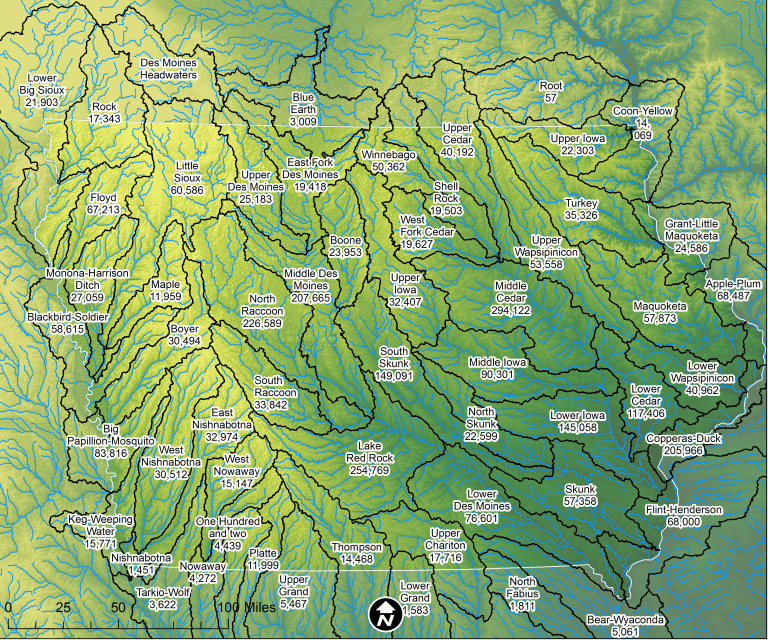

Watersheds are classified by size into what is called a Hydrologic Unit Code (HUC). When evaluating water quality, we frequently look at HUC8 watersheds, which on average are about 1000 square miles. There are 56 HUC8 watersheds in Iowa. My colleague Dan Gilles, a Water Resources Engineer at the Iowa Flood Center, was able to derive the human population for all of Iowa’s HUC8 watersheds.

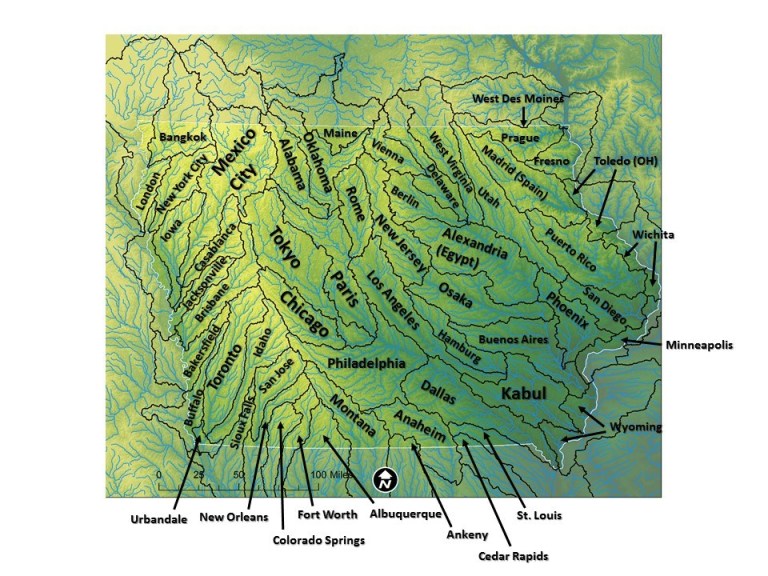

Our most populated watershed, the Middle Cedar, has 294,000 people. Even in that watershed, the human-equivalent livestock population (3.6 million) dwarfs that of actual people. I added the human population to this human-equivalent livestock population for each of Iowa’s HUC8 watersheds and this is illustrated in map below by relating it to a city or state that has a similar human population. I realize that most people will not know the population of many of these places, and the table that follows will help with that.

To finish up, I present this illustration not to make any value judgments on the livestock industry. Clearly it is an important part of our economy. I think we can and should, however, objectively and dispassionately ask ourselves how much we can accommodate while still being able to achieve our desired environmental outcomes. Denmark and the Netherlands both have livestock densities on the scale of Iowa. As a result, both of these countries have in the past suffered environmental consequences similar to our own, but, both country’s governments have intervened in more forceful ways than ours. I’m not saying this is good, bad, or in between, it’s just true.

I think even industry advocates would say there is not much that limits further expansion in Iowa, except perhaps available land in certain areas of the state to apply the waste. Is it reasonable to think about what’s possible when trying to reconcile our desired environmental outcomes with the economic and regulatory considerations the industry wants? If we are going to be honest with ourselves, then I think the answer to that question is yes.

This map shows the human waste equivalent of the people, hogs, laying chickens, turkeys, and dairy and beef cattle the city or state that relates to it with its human population only. Reflected is an average of N, P and TS waste. Only the population of the city proper is reflected, not the overall metropolitan metro area.

Iowa HUC8 Watersheds and the number of Iowans living in them:

Data table used to derive the maps above:

1. http://agrienvarchive.ca/bioenergy/facts.html#Approximate_nutrient_content

2. Jones, C.S., Drake, C.W., Hruby, C.E., Schilling, K.E. and Wolter, C.F., 2018. Livestock manure driving stream nitrate. Ambio, pp.1-11.

Chris Jones grew up in Ankeny and is a graduate of Simpson College. He also holds a Ph.D. in chemistry from Montana State University. Currently he is a Research Engineer at the University of Iowa. His research focuses on water monitoring and water quality in agricultural landscapes.

Top photo: Hog confinement barn interior, sometime before December 2005, via Wikimedia Commons (originally taken from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency).

3 Comments

Why bother to treat human waste?

1st Thanks for the great article.

I was wondering if a city chose to handle their waste like the pork and beef industry and put it into a standing lagoon or spray it on city parks, then the state and federal government would be all over them for breaking the law. Why should taxpayers be forced to spend money when the owners of CAFO’s don’t?

I would like someone to bring a sprayer full of pigs**t and coat the sidewalks outside of the Capital and/or Terrace Hill on a nice windy day and let people decide if we need more control over CAFO’s and their unregulated pollution.

The meat industry is turning our state into a 3rd world country. What young person would want to live in a rural community next to CAFO’s? Then the legislators cant figure out why people leave Iowa? Can’t drink the water and can’t breath the air. Duh!

libre Fri 3 May 2:35 PM

Thanks

Thanks for reading the essay. Your point on treatment (or lack thereof) is well-taken. It is true that human waste is more of a risk to us than animal waste. Nonetheless that magnitude of the animal waste being applied is something for us to consider.

ankenydem Fri 3 May 3:30 PM

I traveled to attend a meeting in the Story County town of Nevada...

…earlier this year. The meeting was of the Story County Board of Supervisors, and one of the agenda items was a discussion of a proposal to build three new hog CAFOs in the area, one of them close to the northern town boundary.

What came through most strongly during that meeting was how one-sided the CAFO siting decision process has become. In certain ways, it barely qualifies as a decision process. To summarize in five words, the hoglots almost always win.

The CAFO builders attended the Supervisors meeting and spoke, but they didn’t really need to. Their plan was going to get approved by the state no matter how many local people objected (and dozens of people did). Their plan was going to get approved even though it was likely to reduce or cut off the possibilities of town growth to the northeast, a direction which otherwise would be one of the more cost-effective growth options.

Their plan was going to get approved even though the Mayor of Nevada expressed strong concerns and even though the Nevada City Council had previously voted to express concern. Their plan was going to get approved even though the Supervisors (of both major political parties) expressed strong concern, and also expressed dismay that the state siting decision process is, as they put it, so outdated that it no longer fits current Iowa realities and concerns.

And as I recall, there was some anger that the CAFO builders had not contacted the City of Nevada about their plans. But why should they, when their plan was certain to be approved?

Theoretically, the benefits of building many more CAFOs in a state that already has so many of them could be balanced with the major costs of CAFOs, including the environmental costs. Then balanced decisions could be made, or at least good-faith attempts at balanced decisions.

But in real life, the CAFO industry has the money and political clout to essentially control state CAFO policies. I’ve lived and voted in Iowa for more than forty years and have watched the CAFO industry rapidly gaining power. So the CAFO political reality is somewhat familiar to me and to many Iowans.

But many other Iowans are not familiar with CAFO realities, especially those who have never felt any personal reason to be concerned. It was interesting, though not in a happy way, to watch during the Supervisors meeting as some attendees appeared to be learning for the first time just how the CAFO decision system really works in Iowa. They were not happy.

In reality, Iowa has already decided, and our state policies make clear, that the benefits of CAFOs officially outweigh every problem they cause.

PrairieFan Fri 3 May 7:23 PM