Devastating news: Iowa Supreme Court Chief Justice Mark Cady passed away on November 15, having suffered a heart attack.

Best known for writing the court’s unanimous opinion in the Varnum v Brien marriage equality case, Cady was a staunch supporter of civil rights. Since becoming chief justice in 2011, he was often the swing vote on Iowa’s high court and concurred in many 4-3 opinions.

Appointed by Governor Terry Branstad in 1998, Cady sometimes aligned with the high court’s conservatives–for instance, on upholding Iowa’s felon disenfranchisement system. Sometimes he joined his more liberal colleagues–for instance, on juvenile sentencing. Cady also authored last year’s opinion that found Iowa’s constitution protects a woman’s right to an abortion. Seventeen months later, three of the five justices who joined that landmark ruling are gone. (Justice Bruce Zager retired, and Justice Daryl Hecht died.)

Bleeding Heartland intends to publish several reflections on Cady’s legacy in the coming weeks. For now, I want to share the chief justice’s remarks at the recent Iowa Summit on Justice and Disparities.

Cady delivered the opening address at the justice summit, organized by the Iowa-Nebraska Conference of the NAACP and held in Ankeny on October 15. Audio:

The chief justice began by saying that all connected to the judiciary “work within a process that is based on fairness, a process that seeks to achieve fairness.”

So it is important when we gather at times like this to talk and to think about obstacles that can interfere with our central objectives, and to work to continuously improve to better meet these objectives.

For me, the process of continuing improvement is a primary part of my job. Our court system is an important part of the overall governing of democracy, and the courts can best contribute to the success of this process of governing by giving voice to injustice when we discover it, and to call people into action, call people into action with the value of justice. Equality, fairness, freedoms, the rule of law become threatened.

Cady focused his attention on “something that can adversely impact our fundamental values and our process of justice: implicit bias.” He’s been speaking to judges, lawyers, and other audiences about this topic for the past several years.

I do this because any form of bias interferes with justice, and we must work to identify implicit bias and remove it from our system of justice, just as we have done with explicit bias. And we must do the same throughout society.

Implicit bias is almost always at the heart of the racial disparities that we continue to discover. We will only truly confront racial disparities when we confront our implicit bias.

Yet as important as it is to confront implicit bias, it can be difficult to discuss. It can be difficult because to talk about our implicit bias can often be mistaken for accusations of being prejudiced or being biased. And can give rise to claims that we should be talking less about it.

The truth is just the opposite. We should be talking more about implicit bias. We need to talk more about implicit bias, but in a respectful and thoughtful way. And we need to talk about the racial disparities in our society without feeling that it’s a putdown to anyone. It is none of these things.

We must remember that when we talk about implicit bias, we are talking about how our brains work, unconsciously. And how it stores up our past, and how it can be often used instinctively to make negative associations about individuals that are not truth.

So we must be careful to accept that the implicit bias that we all have is not racism. It is not bigotry. It is instinctive, unconscious thinking, and can even involve thinking that runs counter to our stated values. But it can result in unintended bias.

The complexity of implicit bias means that it will take much time and effort to overcome. But “we need to be able to talk about it without being negative” or “critical to others,” Cady asserted. “We need to understand it so that we can act more in ways that are consistent with our collective constitutional values.”

If we don’t talk about the problem, Cady warned, “the inequality only threatens to remain hidden in society, and racial disparities will only grow.”

The chief justice then spent several minutes discussing a Scott County success story “as an example of what can be done to address implicit bias and racial disproportionality. This effort shows that solutions can often be as simple as minimizing the consequences.”

Three years ago, a majority of Davenport high school students who were referred to the juvenile justice courts were African Americans, even though less than 5 percent of Davenport residents are black. The impact was far-reaching:

When juvenile offenders find their way into a criminal justice system, too many never get out. Too many are often then hindered by a criminal record and end up having fewer opportunities in life. A life that then contributes to further disparities.

Using research from Georgetown University, the Iowa Judicial Branch established a new process for school referrals in Scott County. (A forthcoming Bleeding Heartland post will cover that program in more detail.) Cady described it this way:

Instead of directing juvenile offenders into the court system, we created a juvenile diversion court for first-time misdemeanor offenders. This diversion court places offenders into a community program, and the courts work as a team alongside the schools, the police, community providers, and parents to provide rehabilitative services.

The results could not be more promising. In 2015, the Davenport school system and the Davenport police diverted nearly all juvenile offenders charged with misdemeanor crimes into the community program. And the recidivism rate was only 16 percent. In 2016, every youth in the city charged with a simple misdemeanor was diverted into the program, and the recidivism rate has been only 7 percent.

The community program addresses the needs of offenders by bringing families into the court system and the community program to interact with their children, and by working with offenders to build on their strengths and to give new insight to prevent future mistakes. A new understanding from this process is being achieved, and criminal records are being avoided.

This new approach “utilizes the science of the adolescent brain development in a positive way,” Cady said. “And it shows signs of reducing racial disparity formerly associated with the treatment of juvenile offenders. And importantly, the juveniles themselves see it as fair.”

The Davenport experience also shows “how we can talk about implicit bias” and how we can deal with data pointing to a disparity, Cady added.

Because when faced with this data, disproportionate referrals of African-American students, the school system, and the police, and the community leaders did not seek to justify it. They did not seek to view it in any demeaning way. They did not seek to deny implicit bias could be at work in the referral of African-American students in disproportionate numbers.

Instead, they were brave enough to work to fix the problem. To eliminate the consequences. And what they are doing today is becoming a model for other communities. Recently a similar model was instituted in Waterloo.

The good news in all of this is that justice is a belief that is a part of all of us. You feel it, and I feel it. We want it for ourselves and for others. And this too, this feeling comes from our brain. The region of the brain that is responsible for our feelings of reward and pleasure.

It means that our instinctive pleasures in life is for life to be fair. And it explains why our founders proclaimed that the very aim of government was to establish justice for all and to create a more perfect union over time.

So while implicit bias can unconsciously work against equality, our implicit justice that lies within each of us is there to work for equality. This is the human trait that we must now rely upon and use to overcome the implicit biases that interfere with our collective belief in equal justice for all.

All Iowa judges have received some implicit bias training, Cady said. The judicial branch is starting “another, more intensive round of training” on this issue.

We want to become better decision-makers, and we know that this can be done by understanding implicit bias, and by seeing others freed from our implicit bias.

But it does not end with judges. All of us need to better understand the perspective of others, free from implicit biases that may hinder our ability to see that understanding.

Jurors, too, need to make decisions free from implicit bias. And for that reason, the Iowa Supreme Court has encouraged judges to instruct jurors on implicit bias, to sensitize them to its existence.

We all benefit. We can all benefit and give ourselves and our government the best opportunity to eliminate racial disparity throughout society.

Cady closed by recalling Rosa Parks’ actions to ignite a movement to end racial segregation in this country. “She was not the first to refuse to yield to the law and give up her seat on the bus,” he noted. Others had done that. But “she was the first to transform that moment into a movement” that opened Americans’ eyes to the violence embedded in all forms of segregation.

Today, we too, we too can use this moment, this summit, to create a movement in Iowa to confront and eliminate all forms of racial disparity that do violence to our collective belief in equality.

Maya Angelou said, “We are only as blind as we want to be.” We can no longer be blind to racial disparity and implicit bias. The time has come for everyone to open their eyes to the injustice of racial disparities and to come together to be the drivers of a movement that eliminates those disparities and bends the arc like never before to achieve that promise of justice for all.

The chief justice was a kind, decent, and thoughtful man. May he rest in peace.

UPDATE: Current and former Iowa Supreme Court justices shared their remembrances of Cady here. Something new I learned from Justice Edward Mansfield’s contribution:

I owe my career as a judge to Chief Justice Cady. About 20 years ago, when he was relatively new to the supreme court and I was relatively new to the state, he and my former spouse struck up a conversation at an event. I then got to meet him and he encouraged me in the process of applying and reapplying in the face of rejection until things lined up just right and I was appointed to the court of appeals in 2009. I cherish my adopted state and cherish him for thinking I might be someone who could serve it.

November 15 news release:

The Iowa Judicial Branch is saddened to report that Iowa Supreme Court Chief Justice Mark Cady has passed away. He was a wonderful individual and exceptional judge, respected and beloved by his fellow jurists. His passing is a great loss to the court and the state he so loyally served. We extend our deepest condolences to his wife Becky and his family.

Statement from the family:

“Tonight, the state lost a great man, husband, father, grandfather, and jurist. Chief Justice Mark Cady passed away unexpectedly this evening from a heart attack. Arrangements are pending.”Chief Justice Cady, Ft. Dodge, was appointed to the Iowa Supreme Court in 1998. The members of the court selected him as chief justice in 2011.

Born in Rapid City, South Dakota, Chief Justice Cady earned both his undergraduate and law degrees from Drake University. After graduating from law school in 1978, he served as a judicial law clerk for the Second Judicial District for one year. He was then appointed as an assistant Webster County attorney and practiced with a law firm in Fort Dodge. Chief Justice Cady was appointed a district associate judge in 1983 and a district court judge in 1986. In 1994, he was appointed to the Iowa Court of Appeals. He was elected chief judge of the court of appeals in 1997 and served until his appointment to the supreme court.

Chief Justice Cady is a member of the Order of Coif, The Iowa State Bar Association, the American Bar Association, the Iowa Judges Association, and Iowa Academy of Trial Lawyers (honorary). He also served as chair of the Supreme Court’s Task Force on the Court’s and Communities’ Response to Domestic Abuse and is a member of the Drake Law School Board of Counselors. Chief Justice Cady is chair of the Nation Center for State Courts Board of Directors and President of the Conference of Chief Justices. He also serves on the Board of Directors, and chairs its Committee on Courts, Children, and Families, and the Committee on Judicial Selection and Compensation. He is the coauthor of Preserving the Delicate Balance Between Judicial Accountability and Independence: Merit Selection in the Post-White World, 16 Cornell J.L. and Pub. Pol’y 101 (2008) and of Iowa Practice: Lawyer and Judicial Ethics (Thomson-West 2007). He is the author of Curbing Litigation Abuse and Misuse: A Judicial Approach, 36 Drake L. Rev. 481 (1987), The Vanguard of Equality: The Iowa Supreme Court’s Journey to Stay Ahead of the Curve on an Arc Bending Towards Justice, 76 Alb. L. Rev. 1991 (2013), and Reflections on Clark v. Board of School Directors, 150 Years Later, 67 Drake L. Rev. 23 (2019). Justice Cady also delivered remarks at the 2012 Drake Law School Constitutional Law Symposium, The Iowa Judiciary, Funding, and the Poor, 60 Drake L. Rev. 1127 (2012) and presented the inaugural Drake Law School Iowa Constitution Lecture, A Pioneer’s Constitution: How Iowa’s Constitutional History Uniquely Shapes Our Pioneering Tradition in Recognizing Civil Rights and Civil Liberties, 60 Drake L. Rev. 1133 (2012).

Chief Justice Cady was an adjunct faculty member at Buena Vista University for more than 30 years and served on its President’s Advisory Council. In 2012 he received an honorary doctorate degree in Public Service from Buena Vista University. Chief Justice Cady received the Award of Merit from the Iowa Judges Association in 2015. He received the Outstanding Alumnus Award from Drake University Law School in 2011, he received the Alumni Achievement Award from Drake University in 2012, and the Judicial Achievement Award from the Iowa Association for Justice in 2016. Chief Justice Cady is also the Iowa chair of iCivics Inc.

Chief Justice Cady is married with two children and four grandchildren.

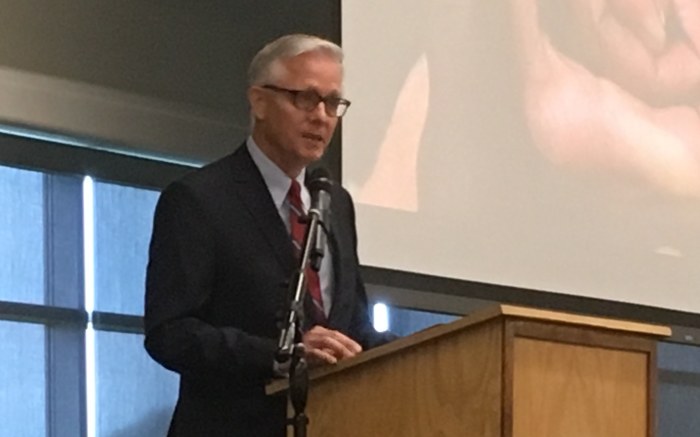

Top image: Iowa Supreme Court Chief Justice Mark Cady speaks at the 7th annual Iowa Summit on Justice and Disparities on October 15, 2019.

2 Comments

A great loss

A brilliant legal thinker and writer. Beyond that, a man of wisdom, grace, and charity who lived his title of “Justice” and infused it with profound humanity.

hcqbach Sun 17 Nov 8:54 PM

A great loss indeed

“What you leave behind is not what is engraved in stone monuments, but what is woven into the lives of others.”

— Thucydides

PrairieFan Mon 18 Nov 6:33 PM