Randy Evans is executive director of the Iowa Freedom of Information Council. -promoted by Laura Belin

We have all become acutely aware in the past few weeks why masks and face shields, respirators and ventilators are so important for hospital workers and their patients.

The supply is not keeping up with the need, and that could have dire consequences for the doctors, nurses, and patients.

Likewise, the novel coronavirus crisis has underscored the importance of another valuable commodity — access to accurate, authoritative information.

As with ventilators and protective gear for hospital workers, the flow of facts is not occurring as smoothly as it should during this public health emergency.

In the past couple of weeks, I have fielded more than a dozen calls and emails about roadblocks the public has encountered in Iowa as people try to stay informed and journalists try to relay to the public information about the scope of the pandemic around our state.

These people have reached out to the Iowa Freedom of Information Council, the nonprofit organization I run, for advice on how to overcome the obstacles thrown up by some government officials — but certainly not all — to block important information people need.

That’s regrettable, because this is the worst time imaginable for government officials and community leaders to impede the flow of facts and details about this crisis.

It is more important than ever for government leaders to make sure they are fully informing the people of this state on the magnitude of the health crisis, the economic downturn it has spawned, and the steps being taken to deal with both of these anxiety-producing occurrences.

Refusing to make public certain facts about the outbreak or the government’s preparation and response only invites skepticism and mistrust by concerned citizens. People will wonder what is being kept from them. Rumor-mongering and conspiracy theories will spread in the absence of authoritative information from our government leaders.

Last week, for example, officials in Cerro Gordo, Mahaska, and Marshall counties all claimed they did not know, or were prohibited from saying, how many tests for coronavirus had been administered at local hospitals. Some said they were not ready to release that information. Others said the information was confidential because of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), the federal privacy law that protects personally identifiable information in patients’ medical records.

There is no justifiable reason under Iowa law for refusing to make public how many test kits or ventilators are available in a county. There’s no reason to refuse to say how many tests have been performed or how many test results have been received so far.

The HIPAA privacy claim is preposterous. No one is seeking the names of people who have been tested. The public is just wanting to know how many people in their communities have received the tests and how many kits are available if local doctors want to test one of their patients who is suspected of having the disease.

These details are important because in the early weeks of the crisis, as the scope of the problem grew daily, there were numerous reports that the tests were nearly impossible to obtain.

One related point about HIPAA: The same officials who cite this privacy law for refusing to make public the number of coronavirus tests they have administered would not hesitate to report how many babies were born at their hospitals last year.

The Iowa Freedom of Information Council’s concerns about access to important information go beyond just the impediments in some counties to finding out how many people have been tested for the virus.

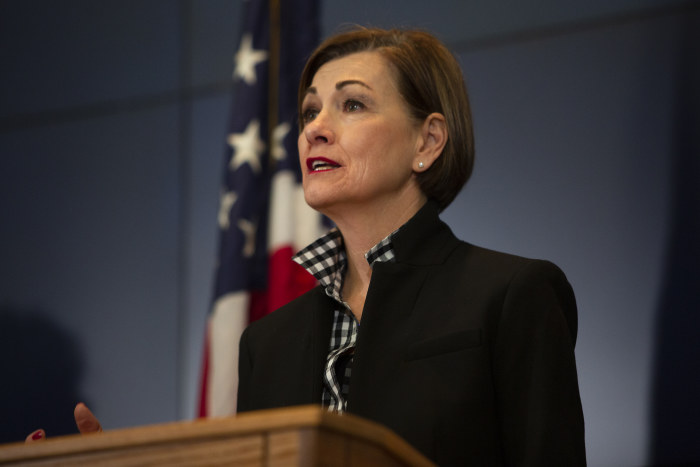

Governor Kim Reynolds has done a commendable job of carving out time in her schedule each day to brief journalists and the public about the crisis. But my organization is concerned about her refusal to allow some reporters to attend these briefings or to ask questions by phone.

Different people get their information from different sources. The job of a governor in times like these is to get important information to all of the people through a variety of means.

The governor does a disservice to her constituents when she and her staff refuse to take questions from journalists like Shane Vander Hart and Laura Belin, among others. Both are respected bloggers who regularly report news about state government. Their political views are miles apart, but their readers deserve to have Vander Hart’s and Belin’s questions answered, too.

As Vander Hart said last week, “Government should not dictate who is press and who is not. Not having access to press conferences does impede our ability to provide information to our readers. …[Laura Belin] and I don’t agree on much, but we agree on this.”

Journalists serve an essential purpose because members of the public are worried about the health and safety of their families, their jobs and their income, but they cannot be expected to individually track down the answers to the myriad questions they have.

I do want to tip my hat to the governor for making clear in her recent emergency orders that state and local government boards and councils must continue to meet in public during this crisis — using conference telephone calls or video conferencing — so the public can continue to monitor the proceedings.

Reynolds’ order recognizes that just as individuals and businesses must adjust their routines to deal with coronavirus, so, too, must state and local government officials.

Top photo of Governor Kim Reynolds speaking at a March 31 news conference by Olivia Sun/Des Moines Register (pool).

1 Comment

Randy Evans, thank you very much

One piece of information that some of us would really like to have at this point may never become available, and that is the real underlying reason, or reasons, why our governor has not only refused to institute a state lockdown, but is not allowing any local lockdowns.

PrairieFan Wed 1 Apr 4:49 PM