Seven U.S. Senate Republicans joined all 50 members of the Democratic caucus in voting on February 13 to convict former President Trump on the sole count of incitement of insurrection. Although the number who voted guilty fell ten short of the 67 needed to disqualify Trump from holding any future office, it was the most bipartisan Senate vote on impeachment in U.S. history.

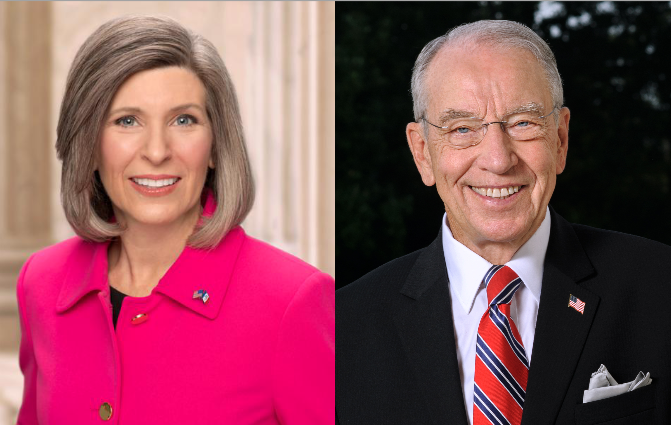

As expected, Iowa’s Senators Chuck Grassley and Joni Ernst voted not guilty. At this writing, neither has released a written statement on the trial. I will update this post as needed.

Pool reporters noticed Grassley failing to pay attention to the proceedings on the third and fourth days of the trial. He has denied those reports.

On the morning of February 13, soon after senators voted to hear witnesses, Ernst told New York Times correspondent Emily Cochrane that the proceeding was a “Total, total shit show” and “a tool of revenge” against Trump. According to Cochrane, Ernst added, “if they want to drag this out, we’ll drag it out. They won’t get their noms, they won’t get anything.”

Senate leaders reached an agreement within a few hours not to call witnesses, so the trial could wrap up quickly.

Shortly after the trial ended, Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer saluted the seven “Republican patriots” in a floor speech. Conversely, he argued that choosing Trump over the country should “be a weight on their conscience” for the 43 GOP loyalists.

Six of the seven Republicans who voted to convict–Bill Cassidy of Louisiana, Susan Collins of Maine, Lisa Murkowski of Alaska, Mitt Romney of Utah, Ben Sasse of Nebraska, and Pat Toomey of Pennsylvania–had voted with Democrats earlier in the week that it was constitutional to try a former president for acts committed while president. Senator Richard Burr of North Carolina cast the most surprising vote for conviction. He said in a statement,

I do not make this decision lightly, but I believe it is necessary. By what he did and by what he did not do, President Trump violated his oath of office to preserve, protect, and defend the Constitution of the United States.

Burr and Toomey are retiring in 2022, so one might argue it’s easy for them to put country ahead of their party’s cult figure. Yet Grassley wasn’t able to take that step, even though he is widely viewed as likely to retire as well, and he voted to remove Bill Clinton from office for far lesser offenses.

I don’t expect Ernst or Grassley to pay any political price for letting Trump off the hook. Most Iowa Republicans remain firmly in the tank for the former president.

On the other hand, very little of any elected official’s career will be remembered 50 or 100 years in the future. This vote will be. History will record Trump’s unprecedented campaign to subvert the peaceful transfer of power, which culminated in a deadly attack on the Capitol. The cowardly decision not to hold him accountable will forever taint the legacies of Iowa’s senators.

UPDATE: Speaking to CNN’s Jeremy Herb, Ernst said of the Republicans who voted to convict, it’s “a very emotionally driven thing.” Her office released this statement:

“As a United States Senator, I swear an oath to the Constitution, an oath I do not take lightly. I’ve said throughout this process my concern is with the constitutionality of these proceedings. The Constitution clearly states that impeachment is for removing a president from office. The bottom line for this impeachment trial: Donald Trump is no longer in office, he is a private citizen. I strongly believe Congress should not be in the business of treating impeachment as a political tool to enact partisan revenge, and if it were to do so, Congress would set a very dangerous precedent, one that is inconsistent with the Constitution I swear an oath to. I urge all of my Senate colleagues to once again refocus on working together for the American people – not ourselves or political ambition, but for the hardworking men, women, and kids across this country who are in desperate need of help and hope.”

Simpson College politics professor Kedron Bardwell characterized Ernst’s statement as “disappointing,” adding, “Frankly, anyone who claims the only purpose of impeachment is removal from office clearly has not read a damn thing that U.S. founders wrote on impeachment.” By way of example, Bardwell cited Federalist Paper number 65 by Alexander Hamilton. He noted that a recent report by the Congressional Research Service found, “it appears that most scholars who have closely examined the question have concluded that Congress has authority to extend the impeachment process to officials who are no longer in office.”

Grassley’s office released a much longer explanation.

U.S. Sen. Chuck Grassley (R-Iowa) today detailed the constitutional, precedential, factual and legal analyses supporting his vote to find former President Donald Trump not guilty of the House of Representatives’ article of impeachment.

In his statement for the Senate record, Grassley reiterated that the January 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol was an assault on democracy itself, and that former President Trump had displayed poor leadership, but stated that the impeachment managers for the House of Representatives failed to prove their case.

“We do not have the authority to try a private citizen like former President Trump. Even if we did, he should have been accorded the protections of due process of law in his trial. And even if we assume he has been, the House Managers still did not prove that he committed incitement to insurrection, the specific crime of which he stands accused. This does not excuse President Trump’s conduct on and around January 6th of this year,” Grassley said in the statement for the Senate record.

Grassley’s full statement for the Senate record follows:

Statement for the Senate Record by Senator Chuck Grassley of Iowa

United States Senate

On the Senate’s Acquittal of former President Donald Trump

February 13, 2021Just barely a year ago I was here making a similar statement. Impeachment is one of the most solemn matters to come before the Senate, but I worry that it’s also becoming a common occurrence.

Before getting into the merits of this impeachment, it is important to reiterate that January 6 was a sad and tragic day for America. I hope we can all agree about that.

What happened here at the Capitol was completely inexcusable. It was not a demonstration of any of our protected, inalienable rights. It was a direct, violent attack on our seat of government. Those who plowed over police barricades, assaulted law enforcement, and desecrated our monument to representative democracy flouted the rule of law and disgraced our nation. Six people, including two U.S. Capitol Police Officers, now lie dead in the wake of this assault. The perpetrators must be brought to justice, and I am glad to see that many such cases are progressing around the country.

While the ultimate responsibility for this attack rests upon the shoulders of those who unlawfully entered the Capitol, everyone involved must take responsibility for their destructive actions that day, including the former president. As the leader of the nation, all presidents bear some responsibility for the actions that they inspire — good or bad. Undoubtedly, then-President Trump displayed poor leadership in his words and actions. I do not defend those actions and my vote should not be read as a defense of those actions.

I am a member of a court of impeachment. My job is to vote on the case brought by the House Managers. I took an oath to render judgment on the article of impeachment sent to the Senate by the House of Representatives. We are confined to considering only the articles charged and the facts presented.

First and foremost, I don’t think this impeachment is proper under the Constitution. This is the first time the Senate has tried a former president. Whether or not it can do so is a difficult question. The Constitution doesn’t say in black and white “yes, the Senate can try a former president” or “no, it can’t.” In contrast, many state constitutions at the time of the Founding specified that their legislatures could, so it’s notable that our federal charter did not. In order to answer this question it’s therefore necessary to look at the text, structure, and history of the Constitution. That’s what I have done. In the end I do not think we have the ability to try a former president.

I start always with the Constitution, which gives Congress the power of impeachment. As I mentioned, impeachment was a feature in many state constitutions at the time and it came from a power enjoyed by the English Parliament.

Impeachment in England was a powerful tool whereby Parliament could hold individuals accountable for actions against the government without having to rely on the King to enforce it. It applied not just to sitting government officials, but also to former government officials, and even to private individuals. It was not simply a way to remove government officials but a general method of punishing the enemies of Parliament, including with fines, jail time, or even death.

This is not the system established by our Constitution. Our Constitution restricts the power of impeachment in two important ways. First, it says that Congress can’t just impeach anyone: only the president, the vice president, and “all civil Officers of the United States” can be impeached. It then restricts the penalties for impeachment to removal from office and disqualification.

A former President is not in any of those three categories. He is not the president. In fact the Constitution also specifies that when the president is impeached, the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court shall preside over the trial. Chief Justice Roberts has not presided over this trial, thus making it clear that it is not the trial of a president. He is obviously not the vice president. He is not a civil officer of the United States.

Because he does not fall into any of these categories, I don’t think that this trial was appropriate.

Moving beyond the text of the Constitution, the history of the Senate confirms this. The United States Senate has never convicted a former official in an impeachment. The Senate has tried three individuals who were former officers—William Blount (a former Senator in 1798), William Belknap (a former Secretary of War in 1876), and Robert Archibald (an incumbent Commerce Court judge in 1912 tried as well for conduct while a District Judge). Belknap is the only executive branch member tried after leaving office. None was convicted for his prior conduct—Archibald was convicted on counts relating to his incumbent judicial service on the Commerce Court. In all three cases the jurisdictional question loomed large at the trial and was cited as an important argument justifying the acquittals. In other words, Senate practice is consistent: it has never convicted a former official in an impeachment.

Between the text of the Constitution and the consistent practice of the Senate, I’m convinced that this is not an appropriate use of our power. While I realize there are arguments on the other side from learned scholars, to me they do not overcome these problems of text and history.

That’s why I voted twice to deal with this impeachment on jurisdictional grounds. But my position didn’t prevail, with the majority Democrats voting in lockstep to proceed, and we went to trial. As I’ve said, even though I think this is inappropriate, I kept an open mind during the process and I listened to both sides as they presented their evidence.

The House Managers tried to prove that President Trump incited an insurrection. That is a difficult argument to make. There were many other articles over which they could have impeached President Trump but this is what the House of Representatives chose. They didn’t meet their burden.

Before getting to the merits of the charge, I need to point out that this impeachment trial has not aligned with principles of due process of law. Other impeachments have involved significant fact-finding in the House, where proper legal formalities are followed, witnesses are heard from and cross-examined, and hard evidence is reviewed. Here there were no hearings in the House. The evidence presented was mostly video montages and news reports. We even had the unusual spectacle of voting to call witnesses for the first time as the trial was ending only to immediately reverse course and call none. Given the seriousness of the situation, I think we should expect better when the House exercises its constitutional duty of impeachment.

This issue involves complicated legal questions. In our legal system, though, it is very difficult for speech to rise to the level of incitement. Incitement is a legal term of art. Usually it takes place in the context of incitement to violence. Incitement, in our legal system, doesn’t mean “encouraging” violence or “advocating” violence or even “espousing” violence. It means intentionally causing likely violence. Because the article of impeachment uses the word “incitement,” I need to evaluate President Trump’s actions under the rubrics of the law of incitement, which were set out in the Supreme Court case of Brandenburg v. Ohio. In that case the Court held that incitement required speech that, first, encourages “imminent lawless action” and, second, “is likely to incite or produce such action.” In other words, in order to succeed the House Managers must have shown that President Trump’s speech was intended to direct the crowd to assault the Capitol and that his language was also likely to have that effect.

As I said before, what happened on January 6 was tragic. We can’t let it happen again. But the House Managers have not sufficiently demonstrated that President Trump’s speech incited it. While I will have more to say about President Trump’s conduct, the fact is that he said this: “I know that everyone here will soon be marching over to the Capitol building to peacefully and patriotically make your voices heard.” That speech is not an incitement to immanent lawless action as established in the case law. I wish the crowd would have listened to him.

Just because President Trump did not meet the definition of inciting insurrection does not mean that I think he behaved well.

To be clear, I wanted President Trump to win in November. I gave over thirty speeches on his behalf in Iowa the week before the election. He—like any politician—is entitled to seek redress in the courts to resolve election disputes. President Trump did just that and there’s nothing wrong with it. I supported the exercise of this right in the hopes that allowing the election challenge process to play out would remove all doubt about the outcome. The reality is, he lost. He brought over 60 lawsuits and lost all but one of them. He was not able to challenge enough votes to overcome President Biden’s significant margins in key states. I wish it would have stopped there.

It didn’t. President Trump continued to argue that the election had been stolen even though the courts didn’t back up his claims. He belittled and harassed elected officials across the country to get his way. He encouraged his own, loyal vice president, Mike Pence, to take extraordinary and unconstitutional actions during the Electoral College count. My vote in this impeachment does nothing to excuse or justify those actions. There’s no doubt in my mind that President Trump’s language was extreme, aggressive, and irresponsible.

Unfortunately, others share the blame in polluting our political discourse with inflammatory and divisive language. As President Trump’s attorneys showed, whatever we heard from President Trump, we had been hearing from Democrats for years. National Democrats—up to and including President Biden and Vice President Harris—have become regular purveyors of speech dismissing and even condoning violence. It’s not surprising that when they talk about taking the “fight” to “the streets” organizations like Antifa actually take to the streets of our cities with shields and bats and fists, destroying lives and livelihoods.

Yes, I think President Trump should have accepted President Biden’s victory when it became clear he won. I think Secretary Clinton should have done the same thing in 2016. But as recently as 2019, she questioned the legitimacy of Trump’s election, saying “[Trump] knows he’s an illegitimate president. I believe he understands that the many varying tactics they used, from voter suppression and voter purging to hacking to the false stories … there were just a bunch of different reasons why the election turned out like it did.”

If there’s one lesson I hope we all learn from not only last year, but the last few years, it’s that we all need to tone down the rhetoric. Whether it’s the destructive riots we saw last summer or the assault on the Capitol, too many people think that politics really is just war by another name. To far too many people, our democracy isn’t free people coming together to make life better for our communities. It’s a street fight.

We don’t need to agree on everything. In fact, part of what makes our democracy great is that we don’t agree on everything. But we do need to resolve these differences with debate and with elections, not with violence. Whether the violence comes from the left or the right, it’s wrong. The same goes for speech that claims to define enemies by political views or affiliations.

We’re all Americans, always trying to form a more perfect union. We have more in common than what divides us. It’s high time those of us who have been elected to serve lead by example. We can take the high road. We can tone down the rhetoric. We can be respectful even when we disagree strongly. If we don’t, we’ll be betraying the trust that the American people have placed in us and we’ll endanger the democracy and the freedom that so many of us have worked to preserve.

These are difficult issues I have considered over the past week. But in the end I am confident in what I think is the correct position. We do not have the authority to try a private citizen like former President Trump. Even if we did, he should have been accorded the protections of due process of law in his trial. And even if we assume he has been, the House Managers still did not prove that he committed incitement to insurrection, the specific crime of which he stands accused. This does not excuse President Trump’s conduct on and around January 6th of this year. It satisfies my oath as a U.S. Senator in this court of impeachment. I therefore voted to acquit.

4 Comments

Priorities

Sen. Grassley’ also questioned President Clinton’s “lack of judgment” (poor leadership, in the president’s case), yet had no trouble voting to convict him of impeachment. I guess, in his eyes, trying to cover up for a blow job is worse than failing to protect the country from all enemies foreign and domestic, which, I believe, is part of his oat and that of the president’s. Strange priorities, there Sen. Chuckles.

DaleAlison Sun 14 Feb 1:05 PM

something that never gets old

Reading Chuck Grassley’s February 1999 speech explaining his votes to convict Bill Clinton. Vernon Jordan helping Monica Lewinsky look for a job = obstruction of justice that justifies removing a president from office.

Laura Belin Mon 15 Feb 9:39 AM

Total sh--t show

The words out of Ernst mouth yesterday describing the hearing. Amazing the words out of the sacred evangelical republican from Iowa.

se Sun 14 Feb 2:57 PM

Please give Sen. Grassley a break

How can you expect an 87-year-0ld to pay attention on the third or fourth day of a trial. His attention span isn’t that long. And he has to give most of his attention at the moment to whether he will run again.

merlin pfannkuch Mon 15 Feb 10:03 PM