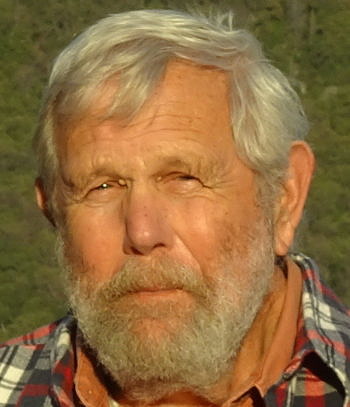

Editor’s note: Paul W. Johnson died on February 15, 2021. His family wanted to share the text of these previously unpublished remarks, delivered to the Iowa Environmental Council’s Annual Conference on October 11, 2013. Paul was introduced by Ralph Rosenberg and recorded by Matt Hauge. Mike Delaney shared this text in a February 16, 2021 special edition of the email “Raccoon River Watershed Association News.”

I can’t help but comment on Ralph; he was the chair of our Energy and Environmental Protection Committee for years in the Iowa legislature when I was there, and when David [Osterberg] was there. We had a wonderful time–it was almost Camelot–we couldn’t do anything wrong. Whatever we wanted to do Ralph would guide us and we got it done. We did REAP [Resource Enhancement and Protection]; we did energy efficiency we did groundwater protection, a number of things, and it was a lot of fun. And it was bipartisan believe it or not; we really worked together.

We had a unanimous vote on REAP in the Iowa House of Representatives. I think there were 98 members there that day, and everyone voted for it, so it was a good time, and I often think back on those times as some of the best times of my life.

Sitting and listening this morning and this afternoon, I don’t know about you but I go back and forth but mostly feel not very good.

We’ve got so much to do, don’t we? You look at all the problems we have, and you look at all the different ways to go about it, and there seems to be even a little bit of tension about “let’s do it this way … no, let’s do it that way,” and it just gets kind of discouraging for me, anyway.

But on the other hand, you take a look back at what we’ve done over the years and where we’ve come from.

I know we tend to be angry and we want to get on with fixing things and so on, but I think now and then we’ve got to stop and think about where we’ve come from, too. I am getting of the age now where I am spending a lot of time looking back.

I was born out in Oakland, California and spent my first ten years there, and the last three or four, I was able to get on the bus and go by myself to Lake Merritt to go fishing where they were mothballing the destroyers at Treasure Island in the Bay at the time. I’d sneak over the fence, and I’d go out with my fishing pole and fish off the bow of the ship, and I’d look down and see my bobber down there–it was a dream for a kid, but I can still close my eyes today and see the raw sewage go by my bobber. Believe me, we have made some progress, and in fact it took regulation to do it–let’s not kid ourselves–it worked. It’s not perfect, though we’ve made tremendous progress.

In the 1960s, I was a milkman on the south side of Chicago and I’d pick up those bottles in the morning, and they’d be covered in soot–and I mean covered in soot. Fifty miles from Chicago you’d drive toward it and see an orange cloud over the whole city. We’ve made progress and let’s give ourselves some credit.

Let’s look at what has worked–go back in the 1930s and the efforts made after the Dust Bowl. If we had continued on my farm like they farmed in the 1930s, it wouldn’t be a farm anymore. The fields were getting divided more and more into smaller pieces as the gullies got bigger and bigger. In the 1970s when I started on the farm that we’re on right now there were gullies everywhere. It was the years of “fencerow to fencerow,” remember? We don’t have that anymore because we don’t have fences anymore, but we certainly still have the attitude.

In 1985, the Farm Bill gave us an array of programs from the Conservation Reserve Program to Conservation Compliance and the Wetlands Reserve Program, and shortly after that the Wildlife Habitat Incentive Program, EQIP, and CSP. These programs have done a lot of good, and it’s true that they’re expensive, but they’re things that we really ought to be thankful for, I think.

When you look at our state, and you go back 150 years or 160 years and dream of what we had–26 million acres of tallgrass prairie, 3 million acres of wetlands, 7 million acres of woods that had never had a cow or a pig in them–and then look at what we did in 50 years, I don’t think anybody has changed their environment so rapidly as we have in Iowa. It’s a pretty special place. We today are probably the most developed state in the country. There’s almost no land in Iowa that isn’t being used. There’s almost no pristine wilderness left; we have no national forests, no national parks, and just little postage stamp size state parks. So we have radically changed it, and yet, we’ve made great contributions to what needs to be done to learn to live on the land without spoiling it.

I can’t help but think very often of what one of my favorite places to go are the wilderness areas around the country. “What that got to do with agriculture?”, you’re going to ask me right now.

Just think about the few people came together starting in about 1915 or 1918 and said, “No, we really need to protect some areas,” and out of that view came the wilderness movement and then in 1964 the Wilderness Act. What’s important for us today is that the real driving force on wilderness protection in our country was a group of Iowans starting with Aldo Leopold.

You’ve all heard of Aldo Leopold, a native Iowan who was the first to really write and do something about wilderness, and who helped establish the first wilderness area in our country, the Gila National Forest in New Mexico.

But he wasn’t alone. There was a landscape architect working for the Forest Service named Arthur Carhart who came with Aldo Leopold, and they surveyed that first wilderness. Arthur Carhart was a native Iowan.

Think of that: they were coming from a state where we domesticated absolutely everything and had nothing wild left. But they’re not the only two. The second wilderness area in our country was the Boundary Waters wilderness and that was saved by an Iowan by the name of Ernest Oberholtzer, who grew up in Davenport, Iowa, and went to Harvard to study classical piano. He took his grand piano up to Rainy Lake in Minnesota and built a cabin there, and he really led the effort to protect the area.

By the way, after Arthur Carhart finished the Gila with Aldo Leopold he went up and helped to establish the Boundary Waters, too.

There were others. Wallace Stegner was born in Lake Mills, Iowa, the same place as Governor Terry Branstad, and as a young person his father was pretty restless and they went west. But Wallace came back and got his PhD at the University of Iowa and married an Iowa native out of Dubuque and became one of the best writers in the West. Wallace Stegner started a writers’ workshop at Stanford and did that for the rest of his life; he also was an alum of the Iowa Writers Workshop.

In 1963, Wallace Stegner wrote a letter to the outdoor recreation committee in Congress called the Wilderness Letter, and I would suggest you Google it and you read it. I think it is the finest definition of why we need wilderness anybody has written and I think it went a long way toward helping us enact the Wilderness Act in 1964.

So out of this state that has nothing wild left in it, that is the culmination of 10,000 years of agriculture, and has tried to domesticate everything, we end up with the wilderness idea and the implementation of the wilderness idea.

Why do I venture that? Because you’re a bunch of Iowans sitting here today, wringing your hands about “Where are we going in agriculture?” and “How can we get agriculture and the environment together?”

I think that this is probably one of the biggest challenges we have in the world today. We’ve got some of the most advanced agricultural practices in the world in Iowa and yet not all’s right is it? We do have problems.

I would argue that we need to step back a little bit and kind of redefine what agriculture is. We’ve focused on agriculture, and what we have focused on is corn and soybeans, but there’s a lot more to agriculture than food and fiber and fuel.

Agriculture in the United States occupies half of our land area in the lower 48 states–a billion acres, in fact. It’s the most productive land in our country both from an economic but also from a biological standpoint, and yet we’ve been driving for 12,000 years now to simplify that land, and we are almost there.

I don’t know about you, but I’ve walked soybeans an awful lot in my life, and if you look in those soybean fields today, there isn’t a button weed in them–or a cockleburr–there isn’t anything in them but soybeans. This is a miracle if your blinders are on and you say that this is what we want to achieve in agriculture. Yet Iowa is a good example: If we really do domesticate everything, is this a state you’re going to want to live in? Maybe if you’re a banker or a realtor or a farmer in the traditional sense maybe yes, but there’s a lot more to it than that, and you’re here questioning today–and we’re all questioning–whether or not what we’ve gained in this great science and this great technology is really where we want to be.

I would argue that we need to redefine agriculture. it’s more than food and fiber and fuel; it’s the care of all life. When you look at Iowa’s 36 million acres and you look at a corn field your first impression is, “Wow that’s beautiful corn,” but is it a beautiful filter for the 32 inches of precipitation that falls on it every year? Is that soil functioning properly? Is it doing more than just holding the roots? Is it also filtering water and partitioning water and buffering water? And is that farmer really a corn farmer or is he a water farmer?

When I think of my farm and I work it now today, I think I’m farming pretty good water right along the Upper Iowa River, and I’m confident that because of the way we farm, the water that’s going through my land today is much much better than it was 35-40 years ago when we started farming that land.

The question for all of us in agriculture, I think, should be “Are we providing for that soil quality to the extent that it’s really functioning the way soil ought to function?” Unfortunately in soil conservation, an area I’ve worked in a lot, our history has been one where if we can increase resistance to soil erosion, then we have solved our problems, and then we are conservationists. Well, that’s just one little piece of what soil is.

Look at soil quality and maybe we’re not doing very well. It’s not good enough just to meter in nitrogen and phosphorus and potassium and maybe even irrigate some water into it. That’s not conservation. Conservation is all of these things. So agriculture becomes multifunctional, not single-functional, and yet even in the strategy that we’re doing right now we’re looking at it mostly in terms of how we can continue to grow 25 million acres of corn and soybeans and still have a little bit better water. What about bluebirds and what about big bluestem and little bluestem and the thousands of other species that we used to share this land with?

It’s not there anymore and we’re still driving even harder so that there’s even less than what we have right now, so when we deal with this it isn’t just the nutrient reduction strategy. If we go in that direction, focusing only on nutrients, we’re getting only a fraction of what we have to get. I think it’s time we stopped and go in a different direction, so I would argue that as we look at our nutrient strategy and water quality issues that we try our best to look at the broader range of things and not just one or two.

We say that we don’t have enough money to do this, and in order to change it’s going to cost too much and we can’t afford it. I’m not sure that’s true. I think if we really put our minds to it, we could do much of what is necessary for quite a bit less than the many hundreds of millions of dollars we are planning on now. I think we ought to give consideration and some thought in discussion to the responsibility of each of us, and that includes farmers, too.

Do we really have a right to pollute and if you want me to stop, then you have to pay me to do it? Maybe we should share the responsibility a little bit. Back when we did the Iowa Groundwater Protection Act, we said it’s going to cost a little bit of money to do better with solid waste, so we raised fees on solid waste, and we all pay a little more to get rid of it, and we’re doing a much better job than we did–still not good enough, but better.

We raised a tax on fertilizers and pesticides and we wrung our hands and said, “We can’t do this,” and yet it was a very small amount and it’s done a lot of good over time and I think we ought to allow more there. In fact, if you look at our yields today if you put a penny on every bushel of corn that’s sold in Iowa, maybe 2 cents on every bushel of soybeans, you’d have 25 to 35 million dollars a year. Put two on and you’d have 70 million a year. You could go a long way to solve many of these problems with a penny or two on each bushel and if you’re getting even 4.50 a bushel, a penny is not going to be that big of a deal.

At the same time, we could look at the federal farm programs and we could do much better than what we’ve done, so I think that to sit and wring our hands and say, “We are not responsible; we can’t do anything” is just wrong we’ve got to do better we’ve got to face these issues.

When we put the tax on fertilizer, I went to the Farm Bureau in Iowa and said, “You let me write the position paper that all your people are voting on across the state of Iowa and we’ll see–because it’s how you ask the question,” and they agreed. They’ve never done that since.

I just wrote a very simple thing saying, “Would you be willing to pay about 5 cents an acre with your nitrogen fertilizer if all that money went back to helping solve the problems in agriculture with the environment?” and the overwhelming number of counties in the state said, “Yes.” That was a pretty big embarrassment for the Farm Bureau.

We did it, and then we did the same with pesticides. And we also did it with household hazardous waste. We did it with gasoline too because we had a problem with underground storage tanks, but the Iowa Constitution says all gasoline tax has to go to the road use tax fund to build roads, but it seemed pretty logical that we should tax gas. Well, in the end we taxed no gas, we taxed nothing, we taxed the gas that evaporated when you filled up your tank. We could calculate what that was and we were able to take that money out of the road use tax fund and use it to solve our problems with leaking underground storage tanks. So there are ways to do it, and I don’t think we should shy from this. I know that taxes are horrible; it’s almost an 11th commandment that “thou shalt not raise taxes,” but I think we need to keep raising that issue and I don’t think we should be discouraged and say we can’t do it.

When I looked over the strategy, my first reaction; this maybe was the same with many of you, was there’s not a whole lot of new science there. There isn’t very much in there that we didn’t say back 26 years ago when we did the Groundwater Protection Act.

One of the things we stressed back then was education, and I know we’ve heard that that won’t do it and we hear that many times we put together a program back then for pesticide applicators in agriculture, not just in agriculture–urban as well and said that you have to go through training and take a test. We did it for private applicators–all farmers essentially back then, as well as commercial applicators.

Wendy Wintersteen put that program together, our dean up there at Iowa State’s College of Agriculture and Life Sciences. It was the best program in the nation by far. She also mandated education on nitrogen management in our pesticide management program. After we implemented that farmers grumbled. Some farmers said, ‘I can’t read, so I can’t take a test,’ so we had to do an oral test for those people, but nonetheless–if that’s true then what about reading a label?

But anyway, we implemented that program, and we had this strong education program on nitrogen management because we felt we were over-applying by quite a bit in Iowa. In five years, we went from 150 pounds of nitrogen on corn in the state down to 114. Now that’s far better than we’re hoping we can get out of the nutrient management strategy today. We stopped doing the nitrogen management program and we’ve slipped back to about 150 pounds again today.

I’ve talked to researchers in this state, though, who’ve said if we had the time and all and could apply it right through side-dressing and through spring application and so on, that corn following soybeans needs really no more than about 90 pounds. Now you’ll argue with me Rick probably but I’m pretty sure he’s done trial after trial across the state and he admitted that he put a little insurance on; he puts 100 pounds on his. He had 200 bushel corn last year in the drought last year but of course we didn’t have the drought so we can do really well if we put our minds to it and we have experience that says that we can do that.

I know we’re wringing our hands about regulatory versus voluntary and it seems to me that “soft regulation”–and that’s what I call conservation compliance–can really do it. We are faced right now with losing that entirely and if Iowa State, the Farm Bureau, and all of you would get up to Washington and raise hell, we would have compliance still on the crop insurance.

Think about what we could do with it now that we know more about how to do it. We could give variable rates of crop insurance depending on how much conservation you put on the land. It’s exciting what we could do. I would expand compliance to all cropland, not just highly erodible lands, because we certainly have problems in lands we don’t define as highly erodible.

Conservation Compliance is probably the most important part of the next part of the next farm bill. The House doesn’t want to do it, the Senate has it in its version right now, but we’ve got to do it and then we’ve got to get to work to make it better than what it has been.

Today I drove over from Iowa City as I said, and that to me that drive from Iowa City to Des Moines used to just break my heart. If you look at the agriculture in that area–it was pretty bad. Today I’ll have to admit I was impressed. It’s not perfect, but it’s far better than it was and that’s because of conservation compliance–it really shifted us into a better attitude and we were doing much much better. Now we’re nowhere near where we need to be, but nonetheless, we know that it can make a difference and it has made a difference. I think that we should care about that.

We talked about buffers here today, and that’s a no-brainer, it seems to me. We should have buffers; we should have field borders; we should have waterways. I would argue we should have a continuous CRP signup for any little piece of land anywhere in any field. You draw a circle around the part that is causing the great deal of problem, you run an environmental benefits index and you enrol it then and there.

In many farms, fifty to sixty percent of the problems is coming from maybe 10 percent of the land, so it seems to me that we ought to just “farm the best and buffer the rest” as was said back in the 90s when we put together that program.

This goes back to the mid-1980s when I put together the legislation in Iowa that would mandate a buffer along every continuously flowing river and stream. We passed it with over 70 votes in the House, and it came within two votes in the Senate of passing, so we came close way back in the ’80s of doing what we’re now talking about maybe doing. Out of that came the buffer initiative. Since we couldn’t do it by law, we went and did it with the programs that we had.

I think it’s important that we push voluntary approaches but they’ve got to be proactive. You’ve got to get out and push it every single day, and you’ve got to preach it to every single person who’s on the land everywhere that you have a responsibility to do better than you’re doing and we’ve got some help for you to do it if you need it. You’ve got to keep pushing it; you cannot just sit back in your office and expect somebody to come and say, “I need help.”

There isn’t a district soil commissioner in this state nor is there a district conservationist in NRCS or a soil conservationist at NRCS that doesn’t know who the bad actors are in their counties. All you have to do if you have a trained eye is look out there and you know what’s good and what’s not good, and yet we never stop and talk to them and say you know you need to do a little better. On the other side when we see good conservation we need to stop too and tell the farmer thanks you’ve done good and we almost never ever see that.

I did that once to a farmer coming down from Decorah. I’d passed him for years, and I was so impressed with what he was doing. He was taking a nap, but his wife was out in the garden working, and I said, “I just want to stop and say thank you.” She started crying on me and didn’t know what to do. So it comes with a cost but it’s one we ought to take on.

But “proactive” is really important. Back when we stared soil conservation in the 1930s, Hugh Hammond Bennett, perhaps the greatest conservationist our nation has ever known, would hold field days–there was one in Iowa that had over 10,000 farmers coming to see how they could put their land back together again. Same was true in Texas, same was true in Ohio. They had to get state police out onto the road to direct traffic from miles around. They’d take a run down farm and in one day they had all the land contractors there, and they even painted the house, and they’d put in ponds, and everybody got a free lunch and took those ideas back home with them.

So don’t underestimate the importance of education, and it can’t quit. That’s one of the things about private lands conservation. Every year there’s a new owner, and in Iowa there’s about 90,000 farms. Every one of them has to be reached and if they’re not we aren’t going to get to where we need to be.

Science is important. I am constantly intrigued by the Des Moines lobe. We’ve heard talk about it today and we’re sitting down at the very tip of it here and we have one of the best research facilities in the world sitting in that Des Moines lobe we’re now improving ag drainage–people are not pulling their tiles out–they aren’t working well and they’re laying new tiles.

What if we stopped everything and we started to think about what could we do in the Des Moines lobe for an agriculture that encourages nature’s services, that will bring biodiversity back onto the land, that will manage water rather than just drain it and keep a place for waterfowl when we need it. In other words, this would be multifunctional agriculture rather than just getting rid of the water for more corn and soybeans.

Think about what was there. It was such a wild place that the Native Americans didn’t even want to go into it because there were too many mosquitoes. At least I think that’s why. And then think about what we did to it: we turned it into a modern miracle.

Like has been said, it is the most productive land in the world today and it is the pinnacle of agriculture–but it’s not the pinnacle of where we need to be in agriculture.

Think about what we’d do if we just put our minds to it and said, “Let’s take this Des Moines lobe or even a watershed or two in it, if we have to start with that, and let’s make it perfect. Let’s bring biodiversity back. Let’s have clean water come out of it; let’s make it aesthetically pleasing. Could we? Let’s not just have straight row after straight row as far as the eye could see.”

I think it would be an exciting project, and it’s something Iowa State should take on. And I say this because Iowa gave us something nobody thought would ever happen; a Wilderness Act in this country and protection of wilderness. We are better positioned than anybody in the world today to give us an agriculture that this world’s going to need. It isn’t only about feeding six billion and then ten billion and then fifteen billion. That’s part of it, but what’s even more important is that it’s a world that has life in it as well the wide array of life that we’ve been so blessed with.

And I’d like to close as I always do with Aldo Leopold and the land ethic. This is the idea that the only way we’re going to get there is that each one of us understands what land is–land in the larger sense, not just the sand, silts, and clays but soil, water, air, wildlife–plants and animals–and people. And how we can all be put together on that land, and how we can care for it?

Leopold felt you pass all the rules you want and you won’t get there. You do all the voluntary you want and you won’t get there. We need both, but even more than that we need the hearts of people who love land and understand land.

“Learn to understand land and when you do I have no fear of what you will do to it,” Leopold said. “And I know of many wonderful things it will do for you.”

That’s where we really have to go in the end and that’s a lot bigger than a nutrient reduction strategy isn’t it? And yet we’ll use the nutrient strategy; we’ll use the good science, but all of us here have to recommit ourselves to making sure we’ll get there.

Thank you for the chance to be with you today.

Paul W. Johnson was a preacher’s kid, former Peace Corps Volunteer, former state legislator, former chief of the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Soil Conservation Service/Natural Resources Conservation Service, former director of the Iowa Department of Natural Resources, and a retired farmer.

2 Comments

Pauls' talk

Paul talked off the cuff (of his rolled up sleeves). He had scribbled notes before he talked. When I asked for a copy of his prepared remarks-he had none. Just a bunch of notes. He received a spontaneous and well-deserved standing ovation. We had many speakers during my tenure as Director of the Council-I do not re-call any speaker receiving the well- deserved praise Paul received.

iowaralph Thu 18 Feb 2:21 PM

Paul was modest in this speech...

…about his role at the Statehouse during the Eighties. But I was there as a conservation volunteer, so I know it took very hard work and determination on the part of Paul and his colleagues to get those conservation bills passed. Those Iowa legislators did Iowa a huge service.

Thank you so much, Paul. May your spirit rest in peace in the Iowa landscape you loved so well.

PrairieFan Thu 18 Feb 4:03 PM