This column by Daniel G. Clark about Alexander Clark (1826-1891) first appeared in the Muscatine Journal.

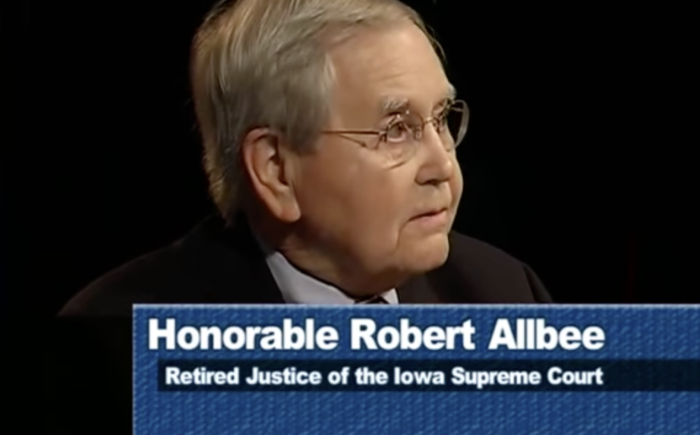

As a boy in one-room Maple Grove school, future Iowa Supreme Court Justice Robert Allbee never heard of the Muscatine man who became the ambassador to Liberia. Attending Muscatine High School, he never learned about Susie Clark, Class of 1871, the ambassador’s daughter and first Black high school graduate in Iowa.

It was a long time before he would learn about the court case called Clark v. Board of School Directors, in which the state’s highest court ruled in the Clarks’ favor and ended “separate but equal” public education in Iowa.

The 1955 Drake Law graduate would serve judgeships at three levels—district, appeals, state—and from 1978 to 1982 as an Iowa Supreme Court justice. He was a trial lawyer and long-time partner in a Des Moines law firm as well.

Justice Allbee’s first cousin, Harvey Allbee, Jr., was Muscatine’s longtime city attorney, who advised the council in the 1970s. That was a time of threatened demolition and litigious relocation of the historic 1878 Clark house, which made way for construction of the Clark House high-rise apartments.

The Allbee ancestors settled in Muscatine County in 1856. (My Clark ancestors did, too. A story for another time.)

Their great-grandfather was Elbert Allbee, whose biography in a 1911 county history begins this way: “For more than thirty years the name of Allbee has been associated with the educational development and progress of Muscatine county.”

From the Muscatine Journal and News-Tribune (April 5, 1935): “Prominently associated with the educational development of the community in various ways, as county superintendent of schools, director and teacher, Mr. [Elbert] Allbee received his early education in the schools of the county and at the Wilton academy. … While residing in Fulton township, he acted as secretary of the township school board for a long period of years, retiring from the post when he moved to Muscatine in 1929.”

At age 90, Robert, the long retired great-grandson, wrote a carefully researched biography of Alexander Clark for publication in the Drake Law Review. That year, 2018, he took part in a series of “Clark 150” sesquicentennial events at Drake University. The law review published the resulting papers analyzing and celebrating the trail-blazing significance of the case, the pioneering equal-rights leadership of the Clarks, and—get this!—the singular role of their school’s founder, Chester C. Cole. Justice Cole wrote the Clark opinion.

In his author’s note, Allbee said he was “proud of the Iowa Supreme Court’s historic record and leadership in guaranteeing civil rights and equal protection under the law to all Iowa citizens.”

Symposium organizer Russell Lovell, emeritus Drake law school professor, wrote,

Some might characterize Clark as a flower blooming in the judicial desert of its time. I prefer to see it as the bright radical star in the night time sky, whose brilliance was too distant to perceive until Chief Justice Earl Warren forged the unanimous opinion in Brown. May Clark’s courage and leadership continue to shine on and guide the Iowa Supreme Court—nay, all courts and all Americans—as the United States continues to strive for an inclusive society where justice and equality are enjoyed by all.

The late Iowa Supreme Court Chief Justice Mark Cady wrote in the same collection,

Remarkably … Iowa became the first state in the nation to reject segregated schools—86 years before the United States Supreme Court did so for all states. … If we can celebrate Clark in a way that highlights the celebration of a process of fairness and equity, the time required to give justice for all will be shortened, and our institutions of government will shine for all.

Shortly before he died, Justice Cady spoke to students at Muscatine High School in 2019. “It took 86 years later before the United States Supreme Court finally did it, and it took some time after when the country actually applied that law, but it started with Susan Clark,” he said. “That’s the significance of that case and your community is at the center of what now is one of our proudest judicial movements in creating integrated places in our country.”

Two days earlier, the modern Muscatine school board renamed combined middle schools as Susan Clark Junior High. It had been 152 years since their predecessors refused to let her enroll at the school near her home.

I celebrated Alexander Clark Day 2022 by writing another column in this series—my fourth in four weeks, thanks to Muscatine Journal editor David Hotle. When Dave proposed a guest opinion for Black History Month, I agreed reluctantly. Now I am finding I have more to say. This is number 5, and I’m on a roll.

Daniel G. Clark is not related to Alexander Clark but is proud to claim him as “brother by another mother.”

Top image: Retired Iowa Supreme Court Justice Robert Allbee discusses the legacy of Alexander Clark in a 2018 interview with Kent Sissel. Screenshot from video posted by Muscatine Access Channel Nine.

1 Comment

"Clark 150" links

Drake Law School’s “Clark 150” documents

https://libguides.law.drake.edu/Clark150

Drake Law Review published papers from Clark 150

https://lawreviewdrake.files.wordpress.com/2019/06/clark-reflections-consolidated.pdf

Iowapeacechief Tue 15 Mar 9:58 AM