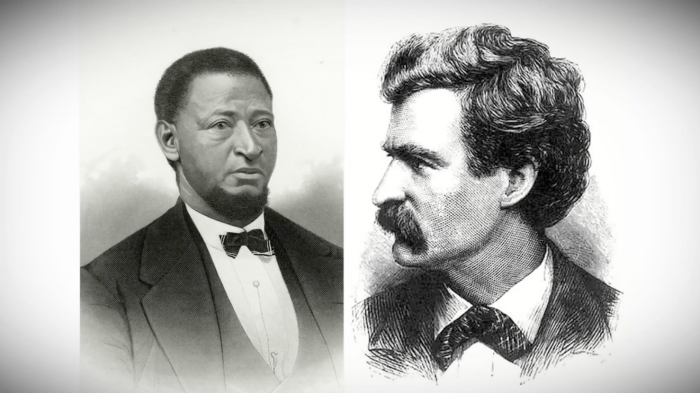

This column by Daniel G. Clark about Alexander Clark (1826-1891) first appeared in the Muscatine Journal.

Whether or not Sam Clemens ever bought a shave or haircut in Muscatine, there’s every chance he knew Alexander Clark.

A 2012 Iowa PBS documentary devotes one-and-a-half minutes (out of 27) to speculation about their acquaintance.

Narrator Simon Estes said in that documentary,

Could it be that the man Clark aided, Jim White, was the basis for one of the most important figures in American literary history—the escaped slave ,Jim, who evades capture by traveling down the Mississippi with Huck Finn?

There apparently is nothing published to suggest this, but in the early 1850s, only a few years after the Jim White case, another young man briefly moves to Muscatine to work on a local newspaper. His name is actually Samuel Clemens—Mark Twain—who, of course, is the author of Huck Finn.

[Kent] Sissel fancies that Clark and the young Clemens might have crossed paths then and talked about the case.

Kent Sissel, present-day owner of Clark’s house, commented in the same Iowa PBS documentary, “If Sam Clemens happened to know Alexander Clark, more than likely the story of Jim White of Muscatine would have been told.”

Young Clark had learned the barbering trade from his uncle, William Darnes, at Cincinnati before working on a riverboat and then settling in the Iowa territory in 1842. His barber career would continue until future son-in-law George Appleton took over in 1868.

Local boosters tout young Clemens’s brief stay in 1854. For several weeks, maybe as long as three months, having followed elder brother Orion from Hannibal, Missouri, he resided at Orion’s home along with their mother and younger brother Henry. Orion had sold his Hannibal newspaper and bought a part interest and co-editorship of the Muscatine Journal.

Henry worked as a clerk at R.M. Burnett’s book store—in the same block as Clark’s barber shop. Sure, I can picture them all trading yarns.

In the documentary, historian Paul Finkelman says,

Being a barber is very important in antebellum America. The safety razor has not been invented, so shaving is a semi-suicidal task for many men. So a lawyer or a doctor or a businessman would have to go to a barber on a regular basis for a shave.

So Alexander Clark is shaving all the important men in town. Black barbers tend to be very high up on the internal Black social scale because they have access to the power structure of white people; they talk to white people. They learn about investments.

Sissel adds: “I think he moved into an absolutely unusual position within the community. I don’t know how any young Black man, at the age of 22, could have positioned himself any better. And I think he had a great deal of support in taking on a role he lived the rest of his life.”

And the inspiration for Jim? We posed that theory in 2013 when Muscatine Community College presented its third in a series of Alexander Clark lectures. The speaker was Terrell Dempsey, author of Searching for Jim: Slavery in Sam Clemens’s World (2003). Let’s just say nobody has proved Kent wrong.

The brother whose slavery views intrigues me is Orion, John Mahin’s partner at the newspaper. He and Clark were the same age, and older than Samuel by 10 years.

Mahin introduced the new co-editor on September 30, 1853—just three months after having set Clark’s name in print for the first time, having reported in July that “A. Clark (barber)” will represent the “colored population of this place…in the National African Convention” at Rochester, New York.

On November 4, in an editorial titled “Slavery,” Orion wrote:

The main difference between Missouri and Iowa consists in the presence and absence of slavery. […]

It is Free State interference which will hold the negro in slavery in Virginia, in Maryland, in Kentucky, in Missouri, for twenty or more years to come—perhaps a half or whole century. Not exactly Free State interference, either, but of that small portion who violently insist upon abrupt, unconditional emancipation.

He got married and moved to Keokuk in 1855. A Lincoln supporter, he later served as the first Territorial Secretary of Nevada and took Sam west with him.

Muscatine Journal, February 10, 1940: “Plans for moving the [Clemens] dwelling from its present location at 108 Walnut street to a permanent site at Riverside park, where it will be preserved as a landmark, were announced here today by Mayor Samuel G. Bronner.”

But the “Old Mark Twain Home” did not get saved after all—a story for another time.

In 1906, in his unfinished autobiography, the elderly Mark Twain recalled the elder brother: “To gain a living in Muscatine was plainly impossible, so Orion and his new wife went to Keokuk to live, for she wanted to be near her relatives.”

And he said: “Born and raised among slaves and slaveholders, he was yet an abolitionist from his boyhood to his death.”

Next time: Emancipation Jubilation

Top image: Screenshot from “Lost in History: Alexander Clark,” documentary produced for Iowa PBS by Communications Research Institute, William Penn University, 2012.