Herb Strentz: The essence of copy editing was not catching errors in spelling or grammar, but making the news more understandable.

When writing posts for Bleeding Heartland, I’ve learned that if you don’t have a good way to introduce a topic, you can find someone who does.

This commentary is about how much we’ve lost as many newspapers have all but eliminated copy editors—people who helped reporters provide the answers and clarity you expect to find in news stories, and saved them from publishing work that raised questions and confusion.

How to sum it up? Consider Michael Gartner’s recollection from when he had just begun working at the Wall Street Journal. (This was some fifteen years before he became editor of the Des Moines Register and Tribune; later he was president of NBC News and won the 1997 Pulitzer Prize for editorial writing as an owner and editor of the Ames Tribune.)

He recalled: “The setting is early July 1960 in the newsroom of the Wall Street Journal:

“In the evening, a rumpled, older man is wandering through the newsroom and stops at the copy desk and wanders over to Michael Gartner, who had joined the paper on June 27. He does not introduce himself.

“Rumpled man: ‘What are you doing?’

“Novice copy editor: ‘Trying to change some things here to make it more understandable.’

“Rumpled man: ‘Good. The easiest thing for the reader to do is to quit reading.’

“Rumpled man wanders off.

“Novice copy editor to slot man: ‘Who was that guy?

“Slot man: ‘Barney Kilgore. He runs the company.’

“Novice copy editor: ‘Oh, shit.’”

That was the essence of copy editing: Not catching errors in spelling or grammar, but making the news more understandable, because the easiest thing for the reader to do is to quit reading.

(Gartner: And here a good copy editor would add a parenthetical aside explaining that a “slot man” was the person in charge of the copy desk in those days—a person sitting in the “slot” of a semicircular desk facing the “rim men” sitting on the outer rim of the desk.)

The biggest hurdle to good copy editing back then was the reporter’s ego.

In recent years, with changes in ownership and demands for profits in the 25 to 30 percent range instead of single digit figures, copy editors seemed easy targets for cutting costs.

Non-newsroom types, whom some sneer at as “bean counters,” could not figure out why, if we paid reporters salaries, we had to pay copy editors, too, to go over reporters’ work. Besides, computer programs supposedly could check spelling and readability and the production processes could be far more efficient. Thanks to computer systems, reporters could not only write their stories but set them in type, too.

A poorly written, pointless or inaccurate story, however, can survive such computer processing and be dumped on readers who find it easy to quit reading. That’s not the case with well edited and even rewritten stories by someone on the copy desk—like Bill Stevens.

Bill worked in the Albany, New York bureau of the Associated Press and shared part of his shift with me when in 1964 I was there, working what was called the “early, early” shift from 7:30 p.m. to 4 a.m.

The “early, early” person would edit and write stories for the next day’s afternoon newspapers.

Bill, on a 3:30 to midnight shift, would handle bureau stories for the next day’s morning papers.

In 1964, Democrat Robert F. Kennedy won a New York U.S. Senate seat, ousting Republican incumbent Kenneth Keating. (Yes, RFK of a prominent Massachusetts family was viewed as an interloper in New York, where he owned property. Yet, in Kennedy humor, his jovial first three words in a speech at the New York Democratic convention were: “Fellow New Yorkers.”)

The race drew attention, less than a year after the assassination of President John F. Kennedy (Robert’s brother). The AP had Relman Morin covering part of the Kennedy-Keating race. Morin had won two Pulitzers, for his coverage of the Korean war in 1951, and for coverage of the Little Rock integration crisis in 1958.

So for the next day’s papers across the nation, Bill was copy editing the work of a deservedly highly regarded reporter.

Pulitzer Prize winner or not, Morin’s story was so awful Bill had to rewrite it from beginning to end. Off it went on the national wire.

At work the next day, Bill said Morin had called the bureau about the rewrite, sent out under his byline because he had written it in the first place, and he was a Pulitzer Prize winner.

In his call to the Albany bureau, Morin offered undying, profuse gratitude. He was drunk while writing the story and when sober, was horrified by his copy. He was so appreciative of Bill’s work that he called the bureau right away to express his relief and thanks.

The episode illustrated not only the value of copy editing, but also the give-and-take and sometimes critical banter that newsroom teamwork not only tolerated but often enjoyed and encouraged.

For a final newsroom war story, consider this one from the Des Moines Register in 1980.

Executive editor Jim Gannon and Register powerhouse political reporters were at the GOP national convention in Detroit. Ronald Reagan would be the party’s presidential nominee, but whom would Reagan choose as a running mate?

Odds favored George H.W. Bush, but former President Gerald Ford and other names fed the rumor mill.

Thanks to their efforts, however, Gannon and his Register colleagues had a scoop. It would be Ford.

So Gannon phoned the newsroom and told Jimmy Larson, running the news desk that night, to go with the headline: “It’s Reagan and Ford.”

But Larson had his doubts and three possible heds were in the running: “It’s Reagan and Ford,” “It’s Reagan and Bush” and “It’s Reagan and ________.”

Gannon persisted. He was the executive editor, after all. Larson still had doubts, but had to make the call, even defy the editor.

Larson would later reflect, “I’d rather be right than be first.”

Time passed, and as longtime Register & Tribune newsroom leader Dave Witke later recalled, Gannon phoned again and hurriedly told Larson to stop the presses. It would not be Ford.

Larson told Gannon there was no need to stop the presses, because he had not started them.

Until Gannon returned from Detroit, Witke said, Larson fretted about his fate at the Register & Tribune.

But upon return, it was thanks that Gannon offered.

Still another reason why copy editors and news editors are missed today. And why you may find it easier to stop reading or stop viewing or listening, for that matter.

P.S.: Copy editing is not a foolproof system. Consider the Chicago Tribune’s famous headline after the 1948 election: DEWEY DEFEATS TRUMAN.

But good editing always has happy endings. Going back to the story about Mr. Kilgore, Michael points out:

“At the Journal in those days it was quite all right to say slot man and rim man since there were no women working there as copy editors. The first woman was not hired until 1967, when the paper hired Barbara McCoy, now known as Barbara Gartner.”

Herb Strentz was dean of the Drake School of Journalism from 1975 to 1988 and professor there until retirement in 2004. He was executive secretary of the Iowa Freedom of Information Council from its founding in 1976 to 2000.

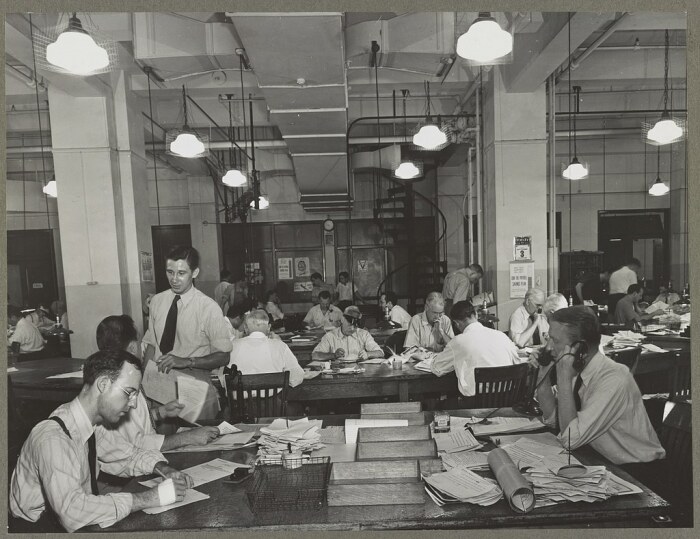

Top image: New York Times newsroom in September 1942. Right foreground, city editor. Two assistants, left foreground. City copy desk in middle ground, with foreign desk, to right; telegraph desk to left. Make-up desk in center back with spiral staircase leading to composing room. Copy readers go up there to check proofs. Photo by Marjory Collins, FSA/OWI Collection (Library of Congress), public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

4 Comments

Thanks

Thanks, Herb for writing and Laura for running this piece. Oh, how I miss copy editors! Grammarly software has it’s place, but nothing can replace the early-eye of a seasoned copy editor. Julie

Julie Gammack Wed 17 Aug 4:55 AM

Grateful for editing

Way back when, I wrote several op-eds that appeared in the REGISTER. One was badly edited, alas. But the others were made much better by good editing, and I learned a lot by seeing how many words could be removed to make my thoughts more readable. And I’m sure the editing also meant my (shorter) thoughts were read by more people, since most readers are busy.

Good editing helps stories become better stories and writers become better writers. I agree with Julie Gammack’s comment. And I really appreciate these essays by Herb Strentz.

PrairieFan Wed 17 Aug 2:01 PM

Make it sing!

Howard Kluender ran “the slot” in the sports dept. when I scored my first job at the R&T at 17. I was an editor for my North High school student paper and thought I knew a bit about tight writing but…..

I did not.

I’ll always be grateful to Howard, Larry Paul, Phil Maly (and even Bill Bryson sr.) who showed me what concise, memorable, informative (and goddam accurate) writing was all about. Thanks Herb, as always, you bring the goods.

dbmarin Thu 18 Aug 8:24 AM

The Digital Curse

Points in the article are well-taken. Copy editing had already endured a serious blow when, beginning in the early 1970s, newspapers switched production and editing of stories from old-stye typewriter and pencil-on-paper to computers. In the paper era, to “edit” meant generally to shorten and tighten copy because it was much easier to simply draw pencil lines through superfluous words and sentences rather. To add sentences and paragraphs on paper copy meant to tear apart the copy, type up the addition, and engage in a messy pasting process. The advent of the computer changed that. All editors found it just as easy to add words and sentences by hitting the “enter” key to open paragraphs as it was to eliminate excess words. The result was that beginning in the 1980s, newspapers waged a losing war against too-long stories. Most readership surveys reported that readers were generally turned off by stories much longer than 15-20 inches and especially didn’t like jumps from page one. But newspapers continued to churn out “longform” articles, and by the end of the century saw their readers defect to the shorter and punchier copy in blogs.

Dan Piller Sat 20 Aug 5:43 AM