Dan Guild is a lawyer and project manager who lives in New Hampshire. In addition to writing for Bleeding Heartland, he has written for CNN and Sabato’s Crystal Ball. He also contributed to the Washington Post’s 2020 primary simulations. Follow him on Twitter @dcg1114.

The U.S. Supreme Court released its decision in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health on June 24. Overturning Roe v Wade caused a political earthquake.

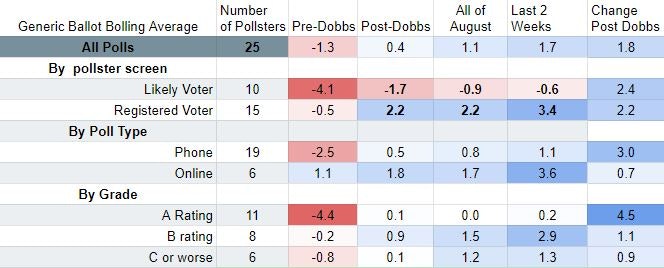

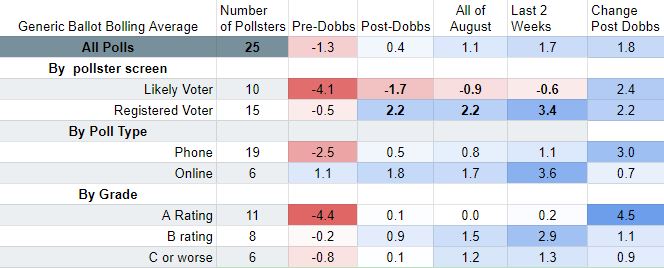

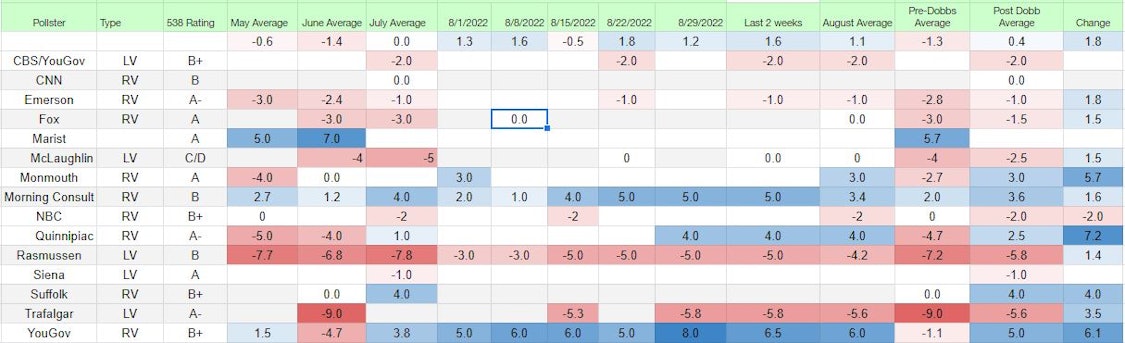

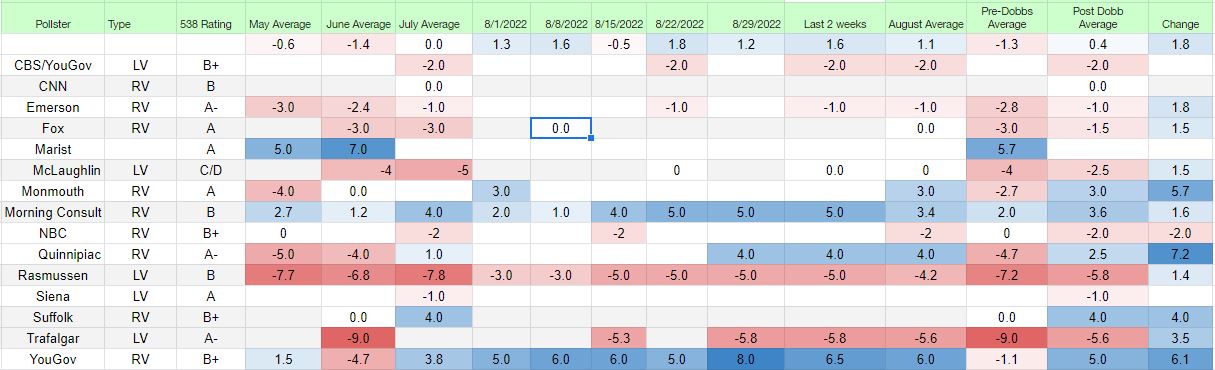

I created this table to show the magnitude of the change in the generic ballot (which asks voters whether they plan to support a Democrat or a Republican for Congress). My averages differ from sites like FiveThirtyEight and RealClearPolitics, because I compare results across time from each pollster, rather than averaging all polls at a point in time. (I will explain why this matters at the end of this article.)

Other notable findings:

The Dobbs decision created about a 2-point shift in the generic ballot polling.

This shift is fairly consistent. Of the 25 pollsters that polled shortly before and after Dobbs decision, 20 found movement toward the Democrats. Moreover, this change appears to be accelerating. In generic ballot polling taken since August 18, the Democrats have opened up 1.8 point lead. This later movement may be a result of the recent improvement in President Joe Biden’s approval rating.

Democrats perform better in polling of registered voters, rather than likely midterm voters.

If there is cause for concern for the Democrats, it is surely this gap between findings for all registered voters and those deemed likely to cast a ballot in November. (Pollsters use different likely voter screens.)

“Better” pollsters have found a larger shift toward Democrats.

Since the Supreme Court overturned Roe, polling firms that receive higher marks from FiveThirtyEight have found more movement in favor of Democrats. On the other hand, those pollsters also are finding a closer race.

I am skeptical of the FiveThirtyEight ratings for reasons that would take a long time to explain. Suffice it to say Quinnipiac gets an “A-“ despite this and this.

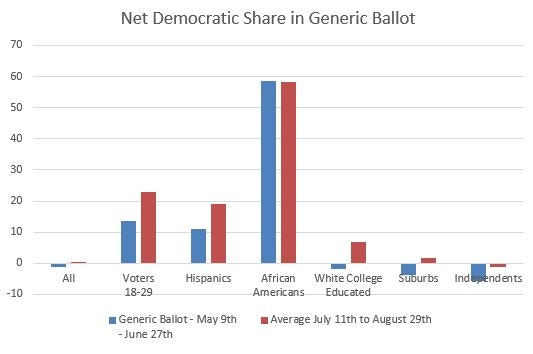

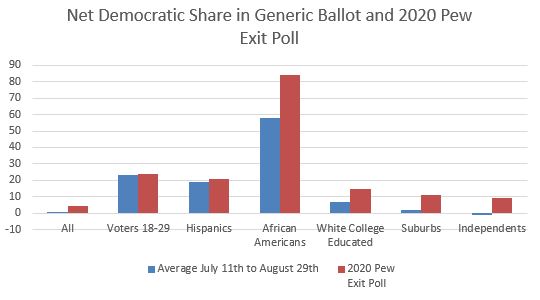

The impact of the Dobbs decision is more noticeable among key Democratic-leaning groups.

The largest shifts are seen among voters between the ages of 18 and 29, Latinos, and college-educated whites—three core elements of the Democratic coalition.

Significant shifts also occurred among independents (where Biden’s approval has not been poor) and among voters in the suburbs. There was no similar shift detected among African Americans.

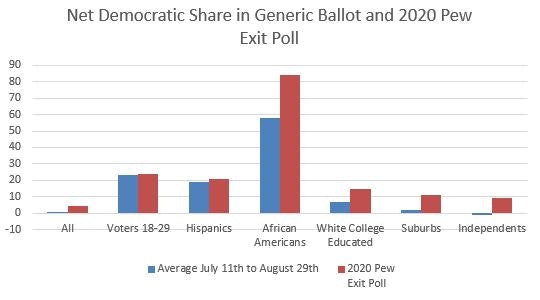

This data gets even more interesting when you compare the shifts since Dobbs to the 2020 election. This chart compares the performance among the same groups as above to the data from the Pew Research Center’s 2020 exit poll.

The Dobbs decision has essentially allowed the Democrats to close the gap between their current support among the young and Hispanics and their 2020 support. But Dobbs did not have a similar effect on African Americans.

My worry with this group is not that Democrats will not match their 2020 margin. Rather, I am concerned large numbers of African Americans may not vote.

In fact, this remains a key question for 2022: will the groups that Democrats rely on turn out in large numbers? Certainly, the Kansas primary election in early August suggests Democratic enthusiasm in the wake of Dobbs is high. Whether that will last to the general election is an open question.

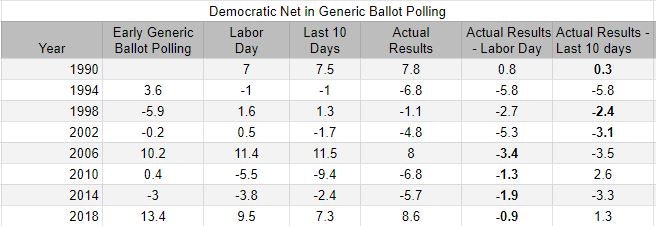

How good is generic polling? The table below addresses that question and reveals two lessons from past midterm elections.

First, generic polling is at best an imperfect measurement. Because the American electorate is so closely divided, small shifts in national opinion can have large electoral results. That was arguably the most important lesson from 2016 and 2020. A shift in 3 points (which is well within the typical error for generic ballot polling) is the difference between a Democratic-controlled House and a Republican one.

The generic ballot polling is simply not good enough at this point to provide high confidence predictions about the results in 2020, particularly when you take gerrymandering into account.

Second takeaway: generic polling on Labor Day has been about as accurate as polling taken during the last ten days of a midterm election campaign. Since 1990, the shifts between this point and election day have been small.

The 2022 midterms will take place in the aftermath of an abortion decision that clearly changed opinion. The campaign is also unfolding against the backdrop of high inflation and gas prices, which may be moderating. The recent decrease in inflation and gas prices may be contributing to a recovery in Biden’s approval rating. (I’ll have more to say about that in a future piece.)

Given the number of unpredictable factors in play, any projection about November would be ill-advised now.

A final note on how I calculated my averages. This chart—as ugly as it is—documents how I arrived at these numbers. The problem with polling averages is that over time, polls from pollsters who have different leans age out of the average.

FiveThirtyEight corrects for that, while RealClearPolitics purportedly uses a methodology (I don’t think they really have one) they have never documented. Either approach risks creating the appearance of movement in public opinion where none exists.

In this chart, I have included only the more active pollsters for simplicity’s sake.

Top image: Protesters gather near the U.S. Supreme Court on May 3, 2022, following reports on a leaked draft of the opinion that would overturn Roe v. Wade. Photo by Drew Petrimoulx available via Shutterstock.