Lora Conrad lives on a small farm in Van Buren County.

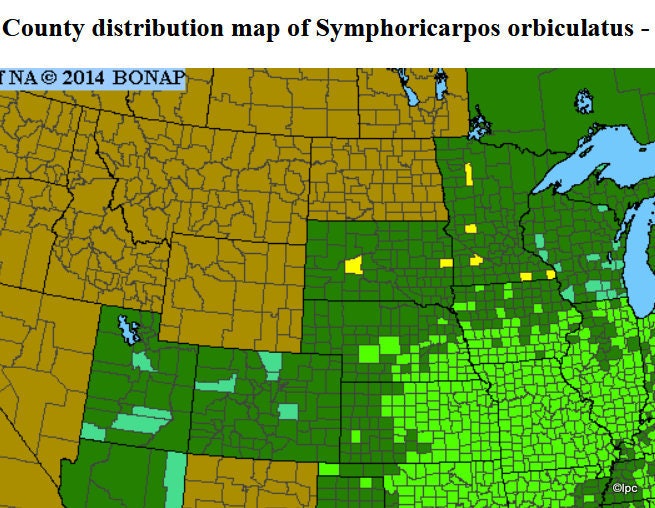

Coralberry (Symphoricarpos orbiculatus) is a deciduous shrub that is native to the Eastern U.S. and much of the Midwest, including Iowa. Its common name describes its fruit or drupe. Other names used for it include Buckbrush and Indian Currant. It is a member of the Honeysuckle plant family. It is more common in southern Iowa, as shown on this map from the Biota of North America Program (BONAP).

Marketmade Styles – hello from the saved content!

Coralberry in Spring

In early spring, one takes no notice of the small dry stems in the woodland background as mosses green, ferns grow and the spring ephemerals begin their show. They are just spindly, brownish-green twigs. But by late May, the newly sprouted shrubs will be ignored no longer, as in some wooded areas they will have become a dense under story plant, as shown here in Van Buren County in late May.

The shrub will be 2 to 4 feet typically, though in ideal conditions it can achieve over 6 feet in height. It spreads both by creeping stolens and seed. These stolens are above ground runners that can be one to eight feet long and that root wherever they touch the ground, while remaining attached to the parent plant. It forms a thicket of under story plants throughout a wooded area. Sadly, this is an indication that these woodlands have been grazed heavily many years ago.

The simple leaves are in opposite pairs along a stem, spaced closely. All are ovate, not usually toothed, and medium green on top but a lighter gray-green underneath.

Coralberry in Summer

Until late July, coralberry plants change little, other than growing more dense and slightly taller. Then buds are formed on the current year’s new branches, but not up where you will notice them. No, the buds are on the underside of the leaves and can barely be detected by looking at the topside of the leaves.

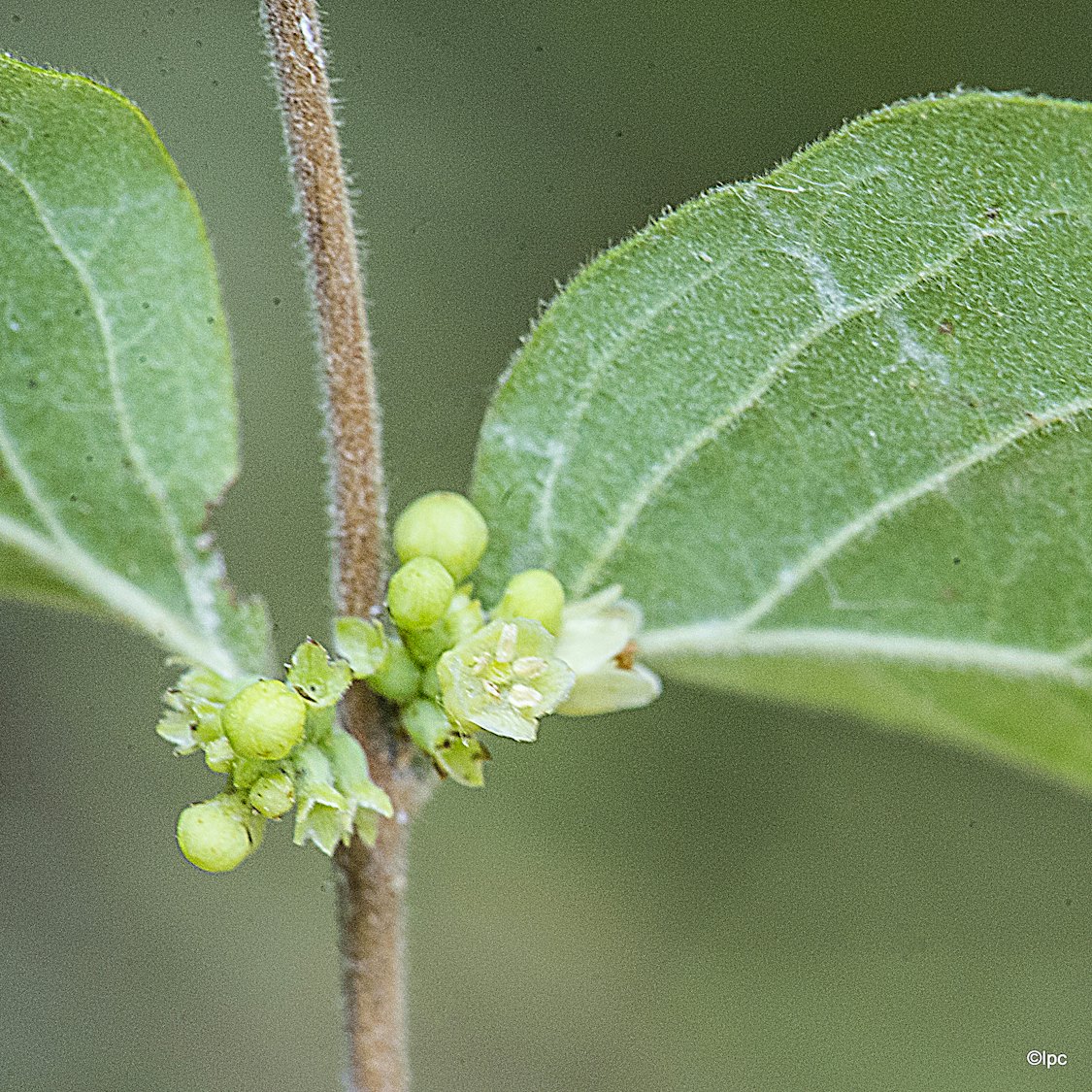

Here is the backside view of a limb showing the just forming small buds in the leaf axils.

The buds and opening flowers can be seen from underneath the leaf, as shown here. The tiny flowers can vary in shade from yellow-green to cream; some have a slight pink tinge.

This view shows the slight fuzz on both the stem and back of the leaf as well as a closeup photo of the small greenish-cream flowers, packed tightly at the leaf axil but forming under the leaf.

This photo shows that in early August, the blossoms can barely be seen from the top side of the leaf:

But by late August, the tiny green drupes are forming. In addition, those that will not form drupes due to drought (or other conditions) have turned brown and will fall aside. More detail is shown in the following photos.

Yet, still at the end of August, the fruit can barely be glimpsed from the top side of the leaves.

By the end of the first week in September, the blossoms are finished, and the berry-like drupes have begun to grow.

Coralberry in Fall

And then, by late September, one can see the slightest bit of red or coral color from the top side of the leaves, as the first photo of the individual leaf shows.

The next photo shows how dense the bushes are as the fruit begins to show:

By the first week in October, the drupes are now colored and finally visible easily from either side of the leaf as shown here. This photo shows the same leaves, turned first to see the top, then the underside.

By the end of October, the drupes are full size. The leaves are beginning to yellow and fall away as they have been frosted and frozen by now.

Here is a detailed view of a cluster of the small drupes in full color. The color can vary from pinkish red to coral to reddish purple. They have pale flesh, are not juicy, and contain a single stony seed each.

Do note that according to Friends of the Wild Flower Garden,

The plants of the genus Symphoricarpos contain toxic saponins. These substances are destroyed by cooking but when eaten raw the chemical is poorly absorbed by humans and most of it passes through. Large quantities would be needed for serious toxic effects.

Moreover, the drupes are not tasty as the saponins give them a bitter taste. The small drupes are so closely packed that they often flatten or change the shape of the fruit as they mature.

This photo, also of mature drupes, documents the variation in color, depending on where the fruit is grown.

By mid to late October, the bushes are glowing with their colorful berry-like drupes. This is when they are most dramatic in a landscape. From now into winter is when Coralberry catches attention.

Coralberry in Winter

In late November, all leaves have dropped from the bushes. Only the darkly colored red drupes are visible against the brown grasses nearby and the gray stems of the shrubs. They hold their fruit in winter, making it both a lovely landscape plant and a source of late winter food for wildlife.

By the end of January, the bushes stand loaded only with newly fallen snow as the fruit has mostly been consumed by now. And here these slight grayish stems will await their late awakening in the coming spring.

Coralberry in your garden

Coralberry typically grows to 4 to 6 feet with its arching branches making an attractive garden shrub. When grown in the open, it develops a rounded, much branched appearance. It tolerates a wide range of soils and will grow in partial to full shade. It is also tolerant of drought, cold and heavy soils.

Several cultivars of this species and hybrid of several other Symphoricarpos species are sold for gardens. It is somewhat difficult to start them from seed, so most are transplanted from young plants that have begun on the stolens. You may buy these from a native plant nursery, or you may find that anyone that has them in their woodland is happy to share. One needs to be sure to keep new runners pruned or removed, as they will spread quickly.

Importance to Pollinators and Wildlife

The blossoms provide food for pollinators, including honey bees as well as native wasps, flies and small bees. Also the Snowberry Clearwing moth and related moths uses Coralberry bushes for caterpillar food (as they do other members of the Honeysuckle family).

Here is a photo of a Snowberry Clearwing on another plant here in Van Buren County. (I did not find one of its caterpillars to photograph. )

The Arkansas Native Plant Society says the following about its attractiveness to wildlife:

Leaves may be eaten by deer (thus another common name: buckbrush) and fruit may be eaten by various birds, but it apparently is not necessarily a preferred food choice for either. Coralberry colonies are used by near-ground-nesting birds and by small mammals for cover.

Studying this plant for a year has been interesting. I hope you find the plant worthy of observation, also.

References

Friends of the (Eloise Butler) Wildflower Garden

Missouri Department of Conservation

5 Comments

So...

What might be the evolved life strategy to essentially hide from sight your flowering parts? My first (and wrong) thought was that bees would simply pass these by, for the more easily seen.

Book recommendation: “The Mind Of A Bee” by Lars Chittka. They know stuff. They learn stuff. They teach stuff. It’s not at all the case that it’s all genetically preprogrammed behavior. Too much for me to try to encapsulate here. It is extraordinary.

So maybe I’ve semi-answered my own question: It doesn’t matter, because bees are smart.

But that doesn’t seem entirely satisfying either, because most flowering plants that bees like don’t do that.

Fly_Fly__Fly_Away Thu 6 Oct 6:16 PM

The Mind of a Bee

Thanks for the book recommendation. I have ordered it. That is a very interesting question and one that is difficult to find an answer. Maybe the book will help with that. There is this article in National Geographic which might hint at the answer, though– https://www.nationalgeographic.com/science/article/bees-can-sense-the-electric-fields-of-flowers

LPConrad Wed 12 Oct 11:53 PM

Helpful photos, interesting essay...

…and I especially appreciate the reminder that coralberry, which I really like, is a member of the honeysuckle family. Invasive Asian bush honeysuckle is a perpetual ecological pain in the posterior, to the point that many Iowa land managers grimace at the word “honeysuckle.” So it’s nice to remember that honeysuckle-family coralberry is a welcome inhabitant of our landscape.

PrairieFan Thu 6 Oct 11:25 PM

Invasive vs Native

Sadly, there are several plants and even some insects that are so similar that we end up destroying our native plant or insect in trying to remove the invading one –the red vs. white mulberries are an example.

LPConrad Wed 12 Oct 11:59 PM

Agreed, that can be a real problem...

…and I heard a sad story a few months ago about a sandy prairie-remnant cemetery in which volunteers were so eager to remove invasive non-native shrubs, which was a worthy goal, that they also eliminated a nice little native shrub that is now uncommon in Iowa and belonged where it was growing in that cemetery. Frustrating.

PrairieFan Thu 13 Oct 2:08 AM