Diane Porter of Fairfield first published this post on My Gaia, a Substack newsletter “about getting to know nature” and “giving her a helping hand in our own backyards.” Diane also maintains the Birdwatching Dot Com website and bird blog.

When the first people walked on the tall grass prairie of North America, they found Baldwin’s Ironweed (Vernonia baldwinii). It can grow almost anywhere the sun shines, including on dry, rocky soil. It’s important for feeding butterflies, moths and especially native bees.

The blooming top looks like a natural bouquet of about a dozen flowers plus some buds that haven’t opened yet. Each one of what looks like individual flowers is actually a smaller bouquet, made up of 20-or-so tiny florets. (Floret = little flower.)

Baldwin’s Ironweed cluster of flowerheads

When the flowers get past it, each floret turns brown and forms a seed, topped by a little tuft of hairs or fibers, which is called the pappus. You get many seeds from each flower head. And if you want to collect seeds, it’s tempting to snatch them up as soon as the flowers turn brown.

Flowers passing, seeds forming

When the plant looked like the photo above, I pinched some of those pappus fibers and tugged. They came out, but I had to pull hard. I could see the little seeds at the base of the pappus, but somehow it didn’t feel quite right. Maybe I’d made a mistake.

The brown seed heads that remained on the plant stayed looking the same for a month or two. Meanwhile, the leaves on the plant slowly turned black and curled up as if burned.

In mid-October, I noticed that the seed heads had changed. They looked like little shaving brushes. The pappus of each seed head was spread out, like an open flower. Tiny individual seeds with their pappus attached were separating from their seed heads, dangling loose or floating away on the breeze.

Then I got it. Nature was showing me that this was the time to collect seeds. The pappus fibers felt soft. I pinched a seed head, and it came away easy-peasy from the plant.

Ironweed seeds ready for harvest

Looking at a seed head, I could make out a tiny seed at the base of each tuft of hairs. Below is one of the individual seeds. The numbered marks on the scale are millimeters. The tip of my little finger would cover a seed of the Baldwin’s Ironweed and its pappus too. (I took this photo with a microscope.)

Baldwin’s Ironweed seed

My guess is that seeds that stay on the plant until they start to disperse naturally are more likely to germinate than ones collected earlier by an over enthusiastic gardener.

Fortunately, I took only a few seeds the first time, so there were plenty left to make another collection. My, how easy it was! As if the ironweed were giving the seeds to me.

I thought of the wisdom of Robin Wall Kimmerer in her wonderful book, Braiding Sweetgrass. When one takes from nature, she advises, take only what is given. (Read the book.) The advice is both ethical and practical. When the seeds are ready, the plant gives them to you.

Maybe those early seeds I collected while the seed heads were still tight will be OK. I’m going to try an experiment next spring. I’ll plant an equal number seeds from each of my two batches of Baldwin’s Ironweed seeds. I’ll keep them separate and note what percentage of the seeds germinates from each group. Just for curiosity’s sake.

Baldwin’s Ironweed in bloom

My guess is that I’ll get a higher germination rate from the ones I collected when the seed heads were loose and ripe, when the seeds came to me like a gift.

And next year, I’ll wait for them.

Scientific name: Vernonia baldwinii

Common names: Baldwin’s Ironweed, Western Ironweed

Plant family: It is in the Aster family (Asteraceae), as are sunflowers and asters.

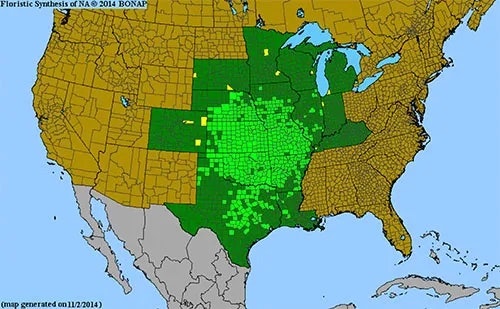

Range: It is native to the very center of North America, especially in Nebraska, Kansas, Oklahoma, Texas, Arkansas, Missouri, and Iowa.

Map from The Biota of North America Program (BONAP) North American Plant Atlas

3 Comments

Lovely photos...

…thank you. I especially liked the inclusion of the bumblebee. Every bumblebee is precious now, as their decline continues.

PrairieFan Thu 10 Nov 9:17 PM

Thanks for this...

Until this year I was not familiar with ironweed. There were a few plants that sprung up on some unmanaged/unmowed land next to me. Its color was quite nice, and I knew “I want that.” So I took some seeds.

And yesterday morning I was scattering a few of those seeds about in my very too little pollinator patch.

Then after reading this post, I spent about an hour last night pulling out the remaining seeds I’d already gathered over the last month, and will scatter more, probably in the spring.

The blooms don’t last as long as earlier bloomers, but the color is great and different and at a time when most everything else has petered out. It proved its drought mettle.

Point taken on the “when ready” rule.

But rules have exceptions. An exception I learned from experience this year: Wild Petunia

I’d found the wild petunia, too, on the same unmanaged land.

Lesson learned:

Take a wild petunia seed pod when it has started to go brown, but still has a bit of green at least around the base. If you don’t do this, when you return the next day you may be out of luck. The seed may have vanished.

What the hell?!?

The answer relates to this second lesson learned:

Don’t store those wild petunia seed pods in an open container. They eventually pop like popcorn, and scatter the small seeds all over the countertop and even down to the floor! You might even hear it happen while you are in an adjacent room. I did.

Anways…thanks for the ironweed post.

Fly_Fly__Fly_Away Fri 11 Nov 2:03 PM

Wow, nice...

…and now I’m wondering what else might be growing on that unmanaged land, and what the history of the land might be. Sounds like it might be worth looking for more natives. Previously-unknown prairie remnants have been discovered by exploring land like that.

PrairieFan Sun 13 Nov 11:41 PM