Nancy Dugan lives in Altoona, Iowa and has worked as an online editor for the past 12 years.

During the Iowa Utilities Board’s October 3 evidentiary hearing on Summit Carbon Solutions’ proposed CO2 pipeline, Summit attorney Bret Dublinske asked landowner Craig Woodward, “Are you aware that in Cerro Gordo County, 83 percent of the route has been acquired by voluntary agreement?”

Brian Jorde, an attorney for landowners who oppose the pipeline, quickly objected. “Irrelevant. And there’s no evidence of that in the record.”

“I think it’s absolutely relevant, and it can be calculated from the Exhibit Hs, but I’ll withdraw the question,” Dublinske responded.

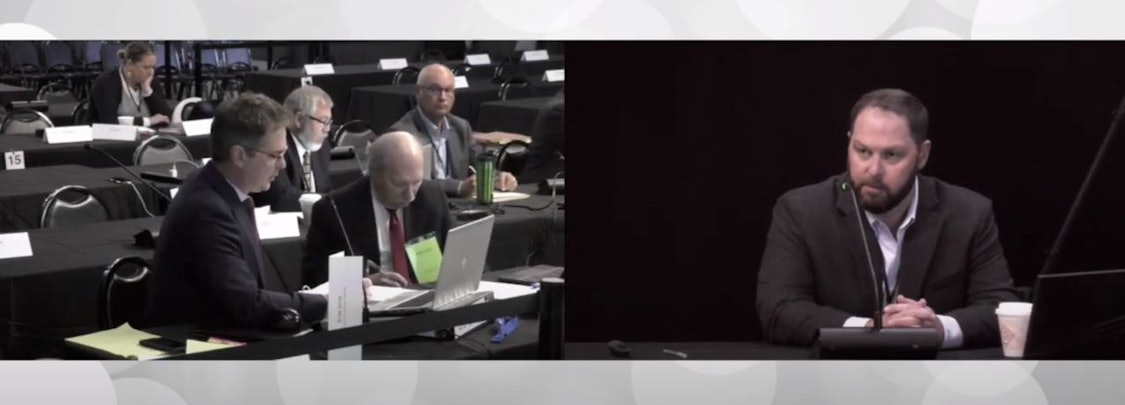

Brian Jorde (left) questions Summit VP Micah Rorie during the September 8 evidentiary hearing (screenshot courtesy of Bold Nebraska)

Dublinske’s argument raises questions regarding the relevance of mediations the Iowa Utilities Board has arranged between Summit and landowners, with the stated purpose of securing easements. Additionally, this is not the first time Summit has advanced this argument. During his September 8 testimony, Summit vice president of land and right of way Micah Rorie boasted of the company’s success rate in securing voluntary easements in Iowa:

Obviously, it has something to do with talking about easement terms and working things out, but, as the project has evolved and as this process has gone on, we – I certainly have been made more and more aware of the public acceptance of the project, as evidenced by where we are in our acquisition numbers.

Jon Tack, general counsel for the Iowa Utilities Board, stated in a September 27 email to Bleeding Heartland that board-arranged mediations, which North Carolina attorney Frank Laney is conducting, are “not relevant or admissible in the evidentiary hearing.” Tack added, “Mediations are voluntary, private discussions between Summit and a landowner that are facilitated by a professional mediator.”

Karl Wendt, procurement manager for the Iowa Department of Administrative Services, told Bleeding Heartland in an October 5 email that he was “not aware of any DAS involvement” in the board’s decision to hire Laney to conduct mediations between Summit and landowners on the path of the proposed CO2 pipeline. The department oversees various administrative rules governing the purchase of goods and services by government officials in Iowa.

It is not known whether the board may have been exempt from these rules in its decision to hire Laney. Tack cited Iowa Code section 476.10 to explain how costs for mediation would be assessed, although that statute does not mention mediation.

Bleeding Heartland asked Tack in an October 4 email:

- How does the board arrange for mediations between Summit and landowners?

- Where are such mediations taking place?

- How many mediations have occurred between May 1, 2023, and October 4, 2023?

- How many mediations have resulted in the finalization of an easement agreement between May 1, 2023, and October 4, 2023?

At this writing, Tack has not answered any of those questions.

MEDIATION AND SELF-DETERMINATION

The American Bar Association’s Model Standards of Conduct for Mediators describe the importance of self-determination in Standard I, paragraph A:

A mediator shall conduct a mediation based on the principle of party self-determination. Self-determination is the act of coming to a voluntary, uncoerced decision in which each party makes free and informed choices as to process and outcome. Parties may exercise self-determination at any stage of a mediation, including mediator selection, process design, participation in or withdrawal from the process, and outcomes.

It remains unclear whether landowners had any say in choosing Laney, who is working in Iowa on behalf of Carolina Dispute Settlement Services, according to Tack.

In their 2014 article on eminent domain mediation, attorney Stanley Leasure and former Fort Smith, Arkansas city administrator Ray Gosack describe the process as follows: “Eminent domain mediation is a process through which a neutral mediator assists a condemning authority – for example, a local government – and a landowner to reach a settlement agreement that each finds acceptable.”

The article goes on to state: “Those in attendance will include the mediator, counsel for both sides, one or more representatives of the condemning authority, and the landowners.”

Leasure and Gosack further explain,

Parties can exercise significant control over the resolution process itself. Rather than being required to adhere to court-mandated procedures, they can focus on the merits of the case and their own interests. The emphasis shifts from compliance with court mandates designed to accommodate a wide variety of civil disputes, to the particular requirements of the condemnation case at hand.

This control can extend to every facet of the dispute, including discovery, timing, and the nature of the dispute-resolution process itself. Mediation almost always yields quicker resolution. The parties to the eminent domain case also have control over the selection of the mediator. Most consider it helpful to employ a mediator with condemnation expertise.

EXPERIMENT OR SLIPPERY SLOPE?

In the Summit matter, the Iowa Utilities Board has encouraged and arranged for mediation, even in the midst of the hearing, before granting a permit and condemnation authority for the project. Many aspects of the process remain a mystery: how the board has arranged such mediations, where they are taking place, how many mediations have occurred, and the success rate.

The article by Leasure and Gosack documents typical confidentiality provisions in eminent domain mediation, which include “inadmissibility at trial of statements made during mediation; protection of the privileged character of information disclosed to the mediator; protection of the mediator from compelled disclosure in judicial proceedings; and introduction of evidence related to the mediation.” It does not call for a complete blackout of information relevant to such proceedings. Rather, it documents in detail a successful eminent domain mediation undertaken by the city of Fort Smith, Arkansas, as the condemning authority, to acquire properties needed to expand a regional water-supply lake.

It’s unclear whether the board’s involvement in arranging for mediations between Summit and landowners affected statements by Dublinske and Summit staff regarding easement negotiations at the evidentiary hearing in Fort Dodge. What is known: during a June 6 status conference, Summit’s Dublinske (an attorney with extensive experience in Iowa utilities law) characterized the proposed mediations as “a bit of an experiment that hasn’t been done in prior proceedings.”

At the June 6 conference, Iowa Utilities Board chair Erik Helland elaborated on the role of proposed mediators:

They would solely be paid for a fixed time, no matter how long it took, and the time would be capped probably at two to three hours, whatever it may be. If it doesn’t settle, they proceed to hearing.

Sierra Club attorney Wally Taylor objected to mediation during the conference:

Certainly we Iowans tend to respect authority, and when the Board tells the landowners, “We have mediation and we want you to take part in it, you don’t have to, but we would like you to do that,” I think they’re seeing that as the voice of authority telling them that they have to take part in mediation.

Helland’s June 6 comments allude to a cutoff point in mediation, which raises one final question: Have board-arranged mediations, especially those that may have taken place during the evidentiary hearing, influenced the proceedings?

1 Comment

Thank you once again, Nancy Dugan

You are asking questions that need to be asked.

PrairieFan Thu 12 Oct 11:00 PM