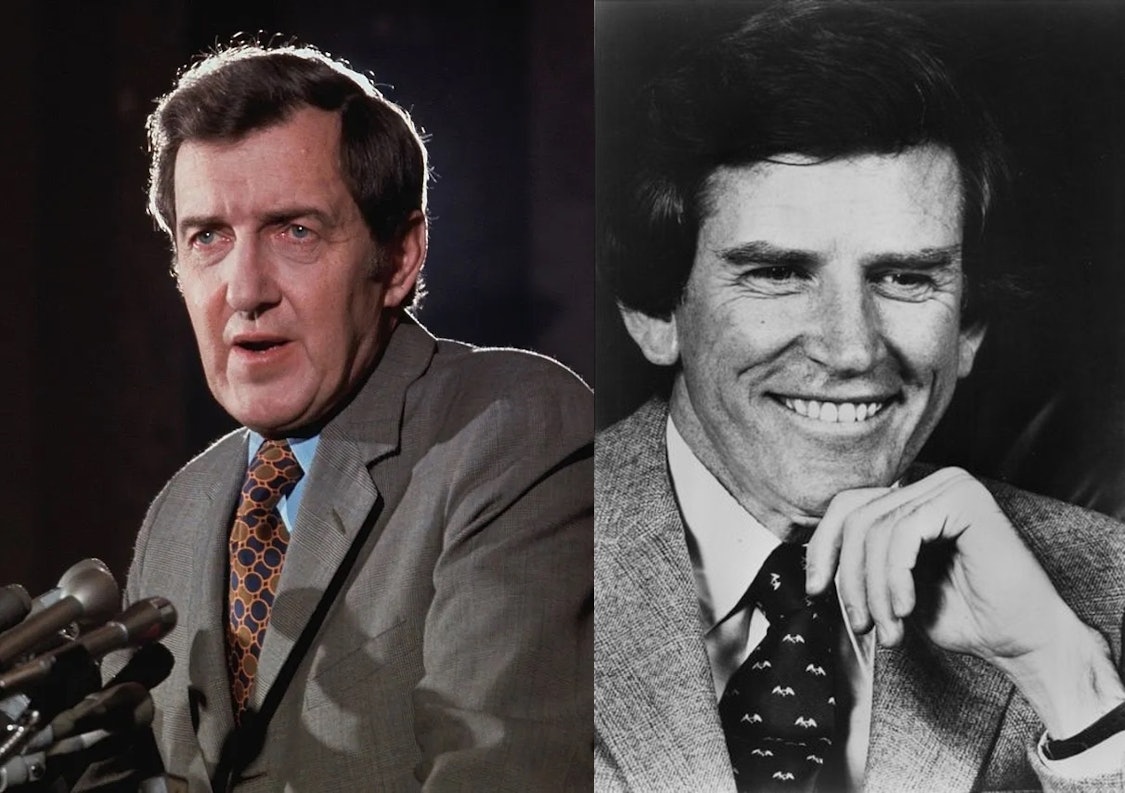

Edmund Muskie, left; Gary Hart, right

Arnold Garson is a semi-retired journalist and executive who worked for 46 years in the newspaper industry, including almost 20 years at The Des Moines Register. He writes the Substack newsletter Second Thoughts, where this article first appeared.

Iowa has been America’s biggest stage for launching presidential campaigns for more than a half-century.

Virtually every presidential election since 1972 has been impacted by what happened in Iowa in January of an election year. During this period, scores of men and women who have wanted to become president of the United States have campaigned extensively in Iowa. They have been on the ground shaking hands in all 99 counties and spent tens of millions of dollars on lodging, transportation, meals, advertising, and more in the state.

It all began in the late 1960s, as America became sharply divided over the rapidly escalating war in Vietnam. As American casualties mounted, the passion among those who favored the war and those who opposed it grew in intensity.

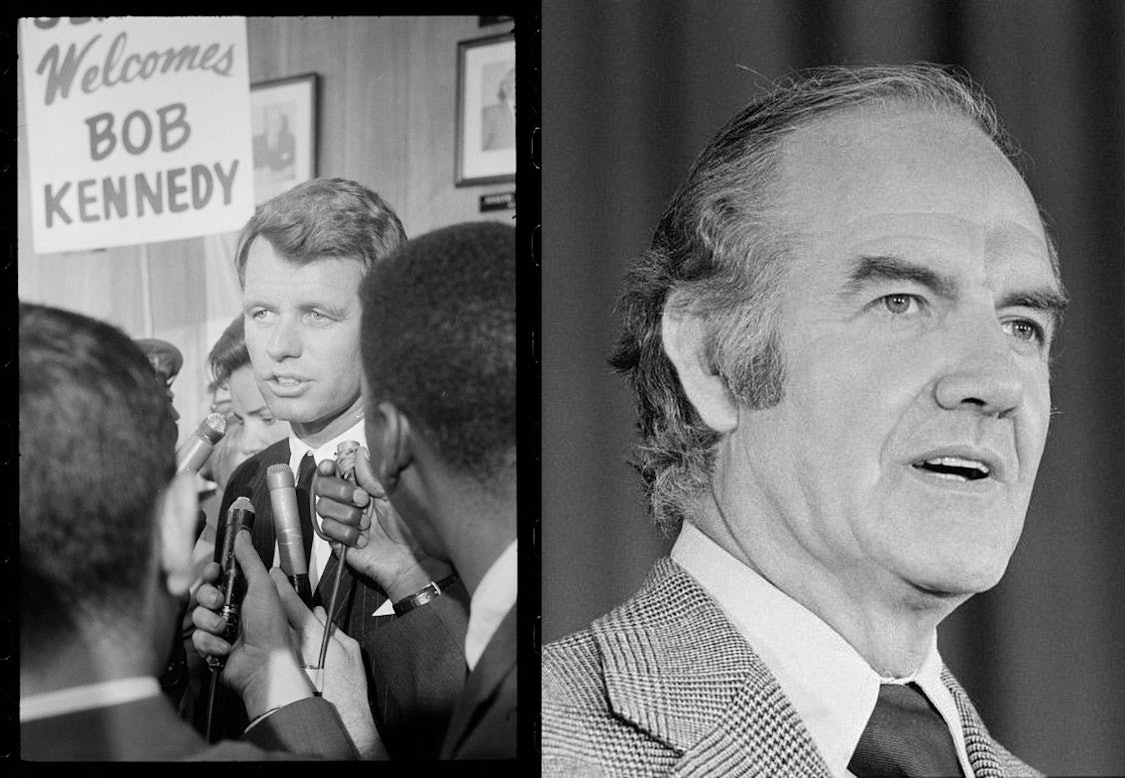

Oddly, the presidential campaign of 1972 began on June 6, 1968, with the assassination of Senator Robert F. Kennedy of New York. Kennedy was shot at the Ambassador Hotel in Los Angeles after winning the California Democratic presidential primary election and appearing to be on his way to the nomination.

South Dakota Senator George McGovern, a Democrat and a Kennedy ally, was in New York at the time. The news hit him hard. Years later, he told me that he went back to his hotel room that evening and stayed up all night trying to process what had happened and thinking about the future of the country.

Left: Robert Kennedy at the 1964 Democratic National Convention; right, George McGovern, 1973

The setting for my conversation with McGovern was a restaurant in Sioux Falls where we were at dinner one evening with our wives after I had become president and publisher of the Argus Leader in Sioux Falls in late 1996.

McGovern, a South Dakota native and a decorated World War II B-24 bomber pilot, had grown to hate the war in Vietnam. As he processed the future of the Democratic Party without Kennedy, he realized several things. A Democratic victory in the 1968 presidential election would be unlikely. The party’s focus soon would be finding a candidate for 1972. The race for the Democratic nomination in 1972 would be wide open. Finally, it seemed probable that with a Republican victory in 1968, the Vietnam War would continue and become the number 1 issue for the 1972 election by a wide margin.

As one of the loudest anti-war voices in the Democratic Party, McGovern began to ask himself a question that evening: “Why not me?” As the wee hours approached, he said, he realized that even though he represented one of the smallest states in the U.S., he could be a leading contender for the nomination. He spent the final hours of that long night developing a plan to become the 1972 Democratic nominee.

HOW IT STARTED: IOWA’S RISE TO FIRST SPOT ON CAMPAIGN CALENDAR

Richard Bender was a young Democratic Party staff member in Iowa in the early 1970s. In the aftermath of the Democratic National Convention in Chicago in 1968, which was disrupted by anti-war rioting, the party became focused on reforms. In Iowa, Bender said, reform demands by anti-war Democrats focused on making the party caucus-convention system democratic. The anti-war Democrats were able to elect a chairman, Clifton Larson, who supported their views. Bender was assigned to develop reforms to deal with issues that had caused anger among party activists.

One goal was to end the winner-take-all system that had governed convention delegate selection. The system had sometimes resulted in one faction with a small majority electing all of the delegates to the next level. Another goal was to end the system in which the county and state party chairs appointed all of the committee members who determined how the party convention would operate.

One solution was proportional representation, through which supporters of each candidate would elect their fair share of delegates. A key detail, later adopted by the national party, was that candidates with less than 15 percent support would get no delegates. Candidates with minimal support thus would fall by the wayside. The selection process would begin at caucuses and work its way up through the county, district, and state conventions.

The proportional representation plan required what, in effect, became a voting process for presidential candidates among caucus attendees. This was in sharp contrast to prior practice, in which delegates were elected with no indication of which candidate they supported, and the national delegates were elected from a list created by a few party leaders.

The second major reform was to elect all of the convention committees from below, rather than having party chairs appoint them. However, elections at every level required taking the time to get organized, draft reports, get them printed, and mail them out to convention attendees in advance. At each level – county, district, and state – this process would take about six weeks.

The time needed to elect all of the convention committees from below would lengthen the caucus-convention process. At each level, time would be required to get organized, draft reports, print them, and then mail them to all of the delegates. Also, a new convention would have to be added at the congressional district level.

On the one hand, it was a complicated process, Bender said. But on the other, it was a process that would give everyone a voice and make a lot of people happy. The bottom line: Happy people translate to election day volunteers to get the vote out. Unhappy people translate to not having volunteers.

Coincidentally, the Iowa legislature decided in 1972 that the latest date the Iowa caucuses could be held would be the second Monday in May. There was no limit on how early they could be held.

OK, put it all together, and the statewide Democratic Party caucus would have to occur much earlier than it had before.

Larson and Bender quickly realized that they had a chance to make Iowa the first state in the country, ahead of the long-standing New Hampshire primary election, to name its choice for a presidential nominee.

“We wanted to be first. OK, it’s true,” Bender said. A date in late January was set. But then, Bender said, he was at the state Democratic headquarters one night, and a call came from a caucus state in the Southwest – he does not remember which state. The caller shared a key piece of information, however — the date they had selected for their caucus. “So, we decided to do it a little earlier. We were going to be first. That was fun.,” Bender said.

He called Larson. “I say, ‘Hey, they’re doing it. We always do it on Monday, so let’s do it the Monday before.’” The caucus date was set: January 24, 1972. And before long, candidates began arriving. So did The New York Times.

Maine’s Senator Edmund Muskie was the early leading contender for the 1972 nomination. But George McGovern had big plans for himself, and his campaign manager, Gary Hart, quickly focused on Iowa’s status as the first state in the nation for voters to express their presidential preferences. It might be an easy way for McGovern to build an identity before the primary elections began in other states.

Muskie finished first with 35.5 percent of the delegates, but McGovern made a surprisingly strong run, finishing second with 23 percent of the delegates. Thirty-six percent remained uncommitted, a number that would fall dramatically in future caucuses. Another half-dozen or so candidates saw their campaigns for the nomination virtually collapse after they failed to reach the 15 percent minimum for viability.

A few weeks later, when Muskie stumbled in New Hampshire and withdrew, after using a derogatory term in reference to French Canadians, a voting bloc in New England, McGovern’s path became wide open. Iowa got the credit and McGovern got the nomination.

However, McGovern would feel hurt for the rest of his life, he told me that night at dinner in Sioux Falls, that he failed to carry his home state, South Dakota. Richard Nixon won in a 49-state landslide, everything except Massachusetts and the District of Columbia.

I told McGovern that one thing about his 1972 campaign had puzzled me for years. Why did he choose not to talk about his decorated war service flying 35 bombing missions in Europe just 27 years earlier? He said it was a subject of debate among his staff, but he decided that using his war record might undermine his credibility as an anti-war candidate. I respected his decision, but it seemed to me that it might have worked for him both ways, allowing him to emphasize how different the two wars were.

1976: A PIVOTAL YEAR FOR THE CAUCUSES

In 1976, the Republicans decided to join the party with a straw poll. Both political parties would caucus on January 16. The two major Republican candidates, Ronald Reagan and Gerald Ford, mostly ignored Iowa, however.

Meanwhile, on the Democratic side, an unknown governor from Georgia with limited funds would bet the farm on Iowa. His relentless campaign helped him finish ahead of several better-known competitors (though behind “uncommitted”). Carter was the biggest winner that night, but the state of Iowa was a strong second.

The Iowa caucuses were on the presidential campaign map, a state in which most candidates from both parties would want to wage a major campaign effort for many years to come. The state basked in its accomplishment of becoming first and fought to maintain its position over the years amid various efforts to knock it farther down in the nomination calendar.

Until 2020.

Iowa Caucus Precinct 15 in Ames during first alignment, February 2020; photo by Rbreidbrown, available via Wikimedia Commons

In 1972, when Iowa Democrats launched their first-in-the-nation presidential voter preference test with a caucus, Bender recalls that there was concern about the party being able to get the results from across the state tallied promptly. The reporters who had come to Iowa to cover the caucus foresaw this. Their message to Bender was loud and clear:

“You know, we want the results that night!” they told him. He listened, and somehow, he made it happen.

It was a message, however, that appears to have been forgotten by 2020, when the Iowa Democratic Party decided – under pressure from the national party – to require the caucuses to report numerous statistics from each precinct. Iowa turned to an untested cell phone app developed by a never-heard-of company.

It was a colossal failure. No one knew the caucus results for weeks. That, coupled with the national party’s ongoing concern about the lack of racial and ethnic diversity in Iowa, was the end of the state’s first-in-the-nation Democratic caucus.

LOOKING AHEAD TO 2028

President Joe Biden, who ended up finishing fourth in Iowa after the results became known—behind Pete Buttigieg, Bernie Sanders, and Elizabeth Warren—decided to reward South Carolina, which had given him a primary election victory that carried him to the nomination. South Carolina would get the first spot in the Democratic Party on the 2024 primary/caucus calendar. It does not matter this year, since Biden is an incumbent seeking re-election. An early Democratic caucus with same-night results in Iowa this year would not draw much attention.

The Republicans, however, kept Iowa first on their calendar. The state has been in the national news for several months with several other candidates seeking to compete against Donald Trump.

But while it might appear to many that with Iowa Democrats not reporting the results of mail-in presidential preference voting until much later (Super Tuesday), its early caucus would be unlikely to generate the kind of national interest it has enjoyed previously, Bender is not sure about that.

He speculates that with a strong Democratic showing in the 2026 off-year elections, which he thinks might be possible, the Iowa Democratic caucus could draw significant attention again in 2028 if the party were to release its results on caucus night. All it would take is a couple of the lower-level Democratic candidates deciding to ignore the wishes of the national party and wage a significant campaign in Iowa. Top contenders might have to choose to campaign in Iowa as well.

And then: Here we go again.

1 Comment

so desperate for national attention

why don’t we try earning respect worthy of the name Democrat by being better allies to peoples who have yet to get a chance to lead? This won’t reverse the anti-representative/illiberal fact that our tiny population gets two Senators but it would be a start..

dirkiniowacity Mon 15 Jan 12:34 PM