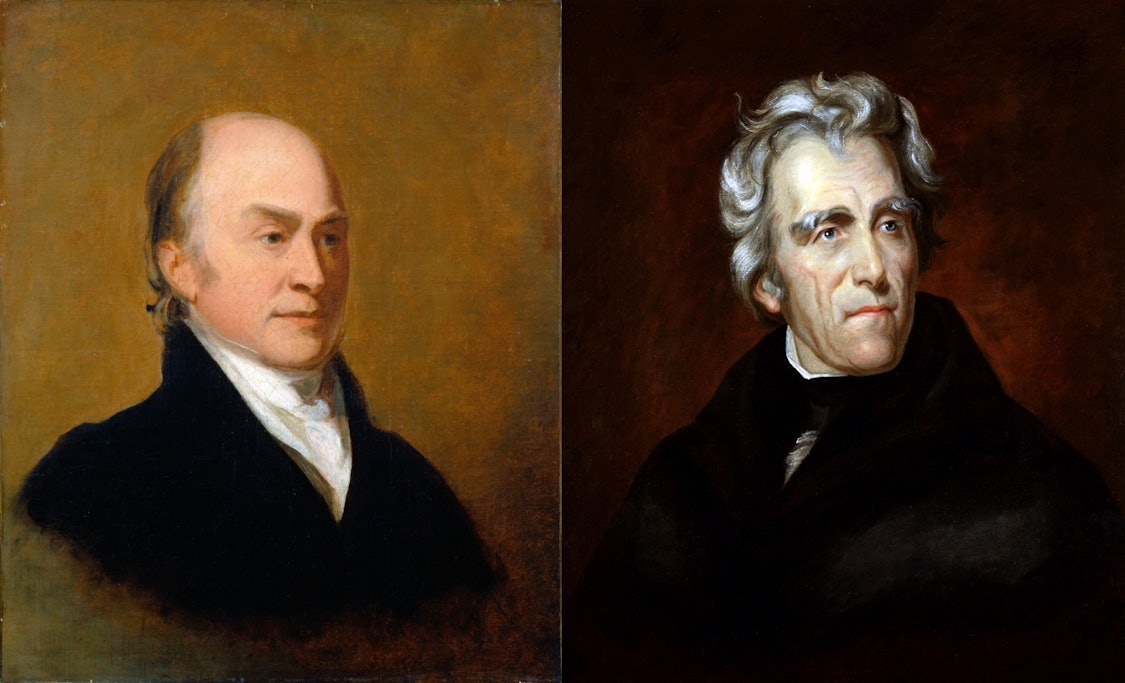

Left: John Quincy Adams, depicted by painter Thomas Sully. Right: Andrew Jackson, also painted by Thomas Sully.

Rick Morain is the former publisher and owner of the Jefferson Herald, for which he writes a regular column.

The 2024 presidential election will in all probability be decided in the usual fashion, with a candidate receiving a majority of the electoral votes declared the winner. That’s the way it’s been done in almost all 109 presidential elections since the nation’s founding.

But not all of them. Exactly 200 years ago, the 1824 presidential election tested the Constitution as never before or since. In some ways the 1824 event seems old-fashioned, while in other respects it was a precursor of our modern contests, including recent claims of a stolen election.

To set the 1824 stage:

James Monroe was wrapping up his second four-year term as the fifth president of the United States. Like three of his four predecessors, he was a Virginia slave-owning planter. Also like those other planter presidents after Washington, he had served as secretary of state before his step up to the presidency. The Southern states had grown accustomed to the procession of their citizens in and out of the White House.

About 10 million people lived in the United States in 1824. But the number who could vote was startlingly small. In the first place, half of them were women, prohibited from voting until almost a century later. About 1.5 million American residents in that year were slaves, and of course they couldn’t vote either. And a sizable number of Americans were below the voting age (usually 21), and therefore ineligible to vote.

Anyway, until 1820, it didn’t matter how many legitimate voting citizens there were: the nominees were selected by the Congressional leadership of the two parties, Federalist and Democratic Republican. The top congressmen would meet and pick their man—-it was a true caucus system, even nicknamed “King Caucus.”

But after 1820, when most states were removing ownership of property as a criterion for white male suffrage, many thousands of newly eligible voters wanted a piece of the action in the nominating process. King Caucus fell into disrepute, and state conventions or legislatures took over, usually selecting someone from their state or region to carry their presidential hopes.

The old Federalist Party, which had been led by George Washington, John Adams (the second president), and Alexander Hamilton, disintegrated after Hamilton was killed in a duel with Aaron Burr in 1804. By the time of Monroe’s presidency in 1817, only the Democratic Republicans remained.

But factionalism within that single party replaced the tumult of previous battles between parties. As a result, five early candidates emerged for the 1824 Democratic Republican nomination, a star-studded lineup rarely seen in American politics. Winning the nomination would virtually guarantee election to the presidency.

At the beginning the five-way race included:

- Senator Andrew Jackson of Tennessee, hero of the Battle of New Orleans in the War of 1812, with other military honors as well, and possessed of a violent temper that led him into at least three duels.

- Secretary of State John Quincy Adams of Massachusetts, skilled diplomat and son of former President John Adams, and possibly the best Secretary of State in U.S. history.

- House Speaker Henry Clay of Kentucky, great orator and extraordinarily skilled politician, supreme leader of the U.S. House for the past thirteen years.

- Treasury Secretary William H. Crawford of Georgia, longtime government appointee in a number of top posts and champion of Southern interests.

- Secretary of War John C. Calhoun of South Carolina, leading proponent of the slaveholding cause and outspoken defender of states’ rights.

Calhoun dropped out of the race fairly early after he proved unable to win enough support in the state legislatures or Congressional delegations. He instead agreed to run for vice president and did so successfully, serving in that position under two presidents. He was one of the rare Americans ever to serve in the House of Representatives and the Senate, and as vice president.

That left four candidates in the presidential race. There was no single election day in 1824. Instead, votes accumulated throughout the autumn. In six states the legislatures chose the electors, and in the other eighteen a popular vote determined those states’ choices. Some electors were not pledged to a particular candidate, and other electors changed their minds after pledging for a candidate initially.

When the electoral votes were finally tallied in late 1824, a unique crisis developed: no candidate commanded a majority of the 258 electoral votes. Jackson won more electoral votes than any of the others, but he came up short. Jackson tallied 99 electoral votes, Adams 84, Crawford 41, and Clay 34.

Jackson also carried the popular vote with 152,901. Adams had 114,023, Crawford 46,979, and Clay 47,217.

The U.S. Constitution provides the method of choosing the president if no candidate achieves a majority of electoral votes, as in the 1824 election: the U.S. House of Representatives makes the choice, from among the top three electoral vote-getters.

Because Henry Clay came in fourth in the 1824 race, he was ineligible for consideration by the House (of which he was Speaker). But Clay wielded immense power in the House, and he set about to persuade his colleagues to elect John Quincy Adams.

Clay shared Adams’ position favoring protective tariffs for American manufactures and federal financial support of internal improvements like railroads and canals, along with continuation of a national bank. Jackson’s support for that “American System” was lukewarm, and he hadn’t had enough governmental experience to suit Clay. And Crawford was strongly opposed to the “American System.”

On January 25, 1825, Clay officially threw his support behind Adams, even though the legislature of his home state of Kentucky had given nonbinding instructions to the Kentucky delegation in the U.S. House to vote for Jackson.

Crawford’s health had deteriorated by late 1824, and because his volatile temper matched Jackson’s, he had alienated many members of Congress. So the contest in the House boiled down one between Jackson and Adams.

Jackson chose to follow the old custom of refraining from personal campaigning for office and letting his supporters take on that task in the House. Adams, on the other hand, personally contacted members of Congress on his own behalf, leaving no doubt of his strong desire for the presidency.

And here was where the election began to generate suspicion. Rumor spread that Adams and Clay had cut a deal whereby if Adams were chosen by the House, he would name Clay as his Secretary of State, the office that traditionally had served as a springboard to the presidency.

The Constitution stipulates that when the House selects the president, each state has one vote regardless of how large the state’s delegation is. On February 9, 1825, Clay’s and Adams’ diligence prevailed, with Adams winning the support of thirteen state delegations out of the then-existing 24, a bare majority. Jackson carried seven and Crawford four.

Jackson exploded. He had received more electoral votes and more popular votes than any other candidate, but in his opinion the outcome was “rigged” by a corrupt bargain between Adams and Clay. He and his supporters immediately set out to oppose Adams’ policies in Congress and elsewhere. For the next four years he claimed that he had been denied what should have been his, and that his campaign effort was “the will of the people.” He nicknamed Kentucky’s Clay “the Judas of the West.”

Four years later, after an unrelenting campaign against everything Adams supported, Jackson defeated Adams decisively in the 1828 presidential campaign and served for two four-year terms, the first Westerner to claim the White House.

He was not the last presidential candidate to rail against a “stolen election.”