Rekha Basu is a longtime syndicated columnist, editorial writer, reporter, and author of the book, “Finding Your Voice.” She was a staff opinion writer for 30 years at The Des Moines Register, where her work still appears periodically. This post first appeared on her Substack column, Rekha Shouts and Whispers.

As of July 1, a new law signed by Iowa’s first female governor will make it illegal for Des Moines to intentionally recruit, hire, or retain female police officers.

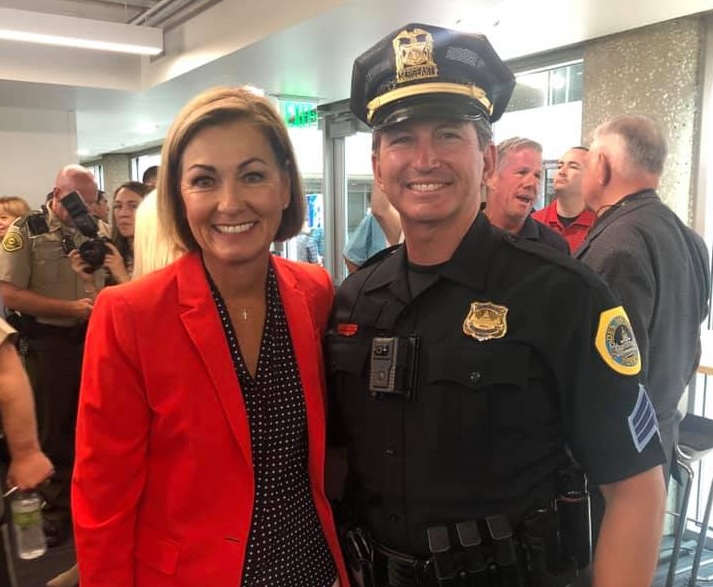

It’s a sad day when Governor Kim Reynolds, a member of an underrepresented group who has benefited from efforts to broaden the mix in power, shuts the door behind her. The very institution of policing will suffer for it and so, besides the women excluded, will those who depend on it to protect us, fairly and equally.

This happens just a year after the Des Moines City Council voted unanimously to pay nearly $2.4 million to four female Des Moines Police Department employees who had suffered discrimination at work. Settled days before it was to go to trial, their lawsuit claimed men in the department were promoted over better qualified women, female employees were subjected to sexual harassment and retaliation for complaining, and harassment was known, tolerated—and in some instances encouraged—by higher ups.

Though some of their allegations dated back to the 1990s, the judge only allowed evidence of cases since 2016. The plaintiffs’ attorney Jill Zwagerman said it wasn’t until the lawsuit was filed that the female officers started getting promoted.

It’s easier for such mistreatment to slide by when women are still in the minority in an institution long defined and dominated by men. A 2022 consultant’s report on the DMPD found just a quarter of employees were female. The department hasn’t provided an updated breakdown since, and my email to a spokesman seeking that information got no response.

But the new law (House File 856) will inhibit any effort to correct the imbalances that enabled that culture to thrive. The biggest share of last year’s settlement—$1.1 million—went to plaintiff Tracy Rhoads. Despite being a senior police officer, the suit described how she felt compelled to cut her hair short and stop using makeup in hopes she would look less feminine, and thereby face less sexual harassment from male colleagues.

It’s horrifying that any employee, much less a senior level law-enforcement officer, should have to feel that way—and then be ridiculed for it. The suit said the officer responded to Rhoads by calling her a “crazy f****** dyke.”

The settlement awarded another senior police officer, Jessica Bastian, $450,000 over what the city admitted were explicit naked photos sent to her by the two-decades head of the police union, Stewart Barnes, who asked for the same in return. Still, following an investigation, he was allowed to retire without consequences in 2020.

And Barnes had a history of undermining the authority of women he worked with. In 2009 he sued the DMPD’s first—and still only—female police chief, Judy Bradshaw, for reprimanding him for defending two officers accused of police brutality in the press.

One of those officers was later convicted in federal court for attacking a civilian—who had to get seven staples in his head—and then lying about it. The other officer pleaded guilty to four felony abuses, for which the city paid out half a million dollars.

Making it illegal to recruit more women when the city is paying out millions over the sexism of majority male employees shows how quickly we forget, or how little those in power care about discrimination in the first place. It’s a safe bet we’ll see more such abuses of power with the new law in place. As Zwagerman told me, “When an organization allows some men to treat their female coworkers as inferior, it’s only a matter of time before they feel emboldened to escalate their conduct.”

“Women at the DMPD have been fighting for a seat at the table for years,” she said. “Our lawsuit helped identify that women were being harassed and were not receiving promotions over less qualified men. I think it will be very easy for the DMPD to go back to not promoting women and claim they can’t promote them now because of anti-DEI laws.”

She also pointed out that so-called “DEI,” (Diversity, Equity and Inclusion) initiatives, policies and hiring by governmental entities which the law forbids, are “nothing more than just asking people to take a look at their business makeup. There were no requirements to have a diverse workforce. There were no quotas. There were no laws fining businesses because they chose a more qualified candidate over another.”

The larger victims of this law will ultimately be the communities the department serves. As former police chief, Bradshaw made concerted outreach efforts, helping build awareness about the prevalence of sexual assault and domestic violence. She was also committed to telling tough truths within the department, holding it to high standards.

But she herself faced prejudices when first applying to Iowa police departments, where she was told by several in charge that women weren’t welcome. It took being recruited in 1980 by Sgt. Phylliss Henry, who had become the first female DMPD patrol officer in 1972. And despite Bradshaw’s extensive qualifications, including a master’s degree in public administration, city administrators dragged their feet on naming her the chief in 2007 when the position became vacant.

No matter how much progress is made, if the efforts aren’t constantly reinforced, there’s a risk of sliding back. Sexism endures. And most successful women, especially from underrepresented populations, stand on the shoulders of others who helped pave the way.

That should be celebrated, not legislated against as if it were preferential treatment. But these are thinly veiled ploys by people of power and privilege to keep it for themselves.

We can’t afford to go backwards, and we won’t be bullied into it.

Editor’s note from Laura Belin: House File 856, which prohibits state entities, local governments, and community colleges from engaging in DEI activities, cleared the Iowa Senate on a party-line vote of 34 to 16. The Iowa House approved the final version of the bill by 59 votes to 32, with Republicans Michael Bergan, Matthew Rinker, and Brent Siegrist joining all Democrats present to oppose the legislation.

Top photo of Governor Kim Reynolds with Sgt. Paul Parizek, public information officer for the Des Moines Police Department, was cropped from an image originally published on the governor’s official Facebook page on June 17, 2021 (the day she signed a law granting sweeping qualified immunity to Iowa police officers and enhancing penalties for various protest actions).

3 Comments

More Failed Republican Leadership

As I’ve shared in this space previously, I worked in hospital management for over 40 years.

I estimate that around 80 percent of my-coworkers were female. Among the highlights of my career was offering increased opportunities for women to serve in leadership.

While it shouldn’t have to said in 2025, I will nonetheless . . . women are as talented, dedicated and tough as any male counterpart. In many cases, more so.

Once again, Governor Reynolds and the Republican legislature is using its super majority to score meaningless political points.

The Des Moines Police Department will not become better because of this narrow-minded legislation. It will most likely increase discrimination and bad conduct towards women only seeking to serve their community.

Elected Republicans in Des Moines have no clue what it takes to manage an organization with critical public service responsibilities.

They currently have the power to make their cynical political statements. But our public institutions only become increasingly more degraded under failed Republican leadership.

Bill Bumgarner Thu 19 Jun 10:40 AM

hey BB they aren't just making/scoring political points

they are (as the author here notes) enforcing a kind of reactionary social and political order not unlike the one outlined in Project 2025 and currently being enacted in all branches of our federal government. They don’t want just any police-state but one where women are largely home raising children, people of color know their proper place, poorer people stay poor and dependent on Capital, and queer people don’t exist. For them these are the “critical public service responsibilities” and they are quite explicit about this.

dirkiniowacity Thu 19 Jun 10:51 AM

I was gobsmacked...

…when I came across the website of a very-right-wing American religious leader who basically said that there will always be problems when men and women work together, especially if women supervise men, because a very strong drive to be and stay in charge is part of what it means to be a real man.

The leader was not Christian. It seems that very-right-wing fundamentalists of many religions have some beliefs in common.

PrairieFan Thu 19 Jun 8:10 PM