The Iowa State Association of Counties has asked the Iowa Supreme Court to keep tens of thousands of citizens permanently disenfranchised so county auditors will have “a definition of infamous crime that can be easily discerned and quickly applied” as they administer elections.

In addition, the association representing county officials suggests auditors will be unable to provide “the orderly conduct of elections” if the high court does not abandon efforts to distinguish certain felonies from the “infamous crimes” that disqualify Iowans from voting under our state’s constitution.

The disturbing attempt by county governments to place administrative convenience above a fundamental constitutional right came in a “friend of the court” (amicus curiae) brief filed in connection with a case the Iowa Supreme Court will consider this week. Yet Polk County Auditor Jamie Fitzgerald, the chief elections officer in Iowa’s largest county, maintains that a new standard allowing some felons to vote would not be “an administrative burden any more than the myriad other provisions that county auditors and poll-workers must contend with.”

BACKGROUND

The Iowa Supreme Court will hear oral arguments on March 30 in Kelli Jo Griffin’s lawsuit challenging “Iowa’s statutes, regulations, and procedures that permanently bar all Iowans with a felony conviction from voting unless the Iowa Governor has restored their right to vote.” Since January 2011, Iowa has had one of the most expansive state bans on felon voting. The system has made it “just about impossible” for people to regain their voting rights years after completing their prison terms or probation, even for non-violent crimes.

Griffin argues that the current system violates her right to vote and to receive due process, and that her “prior felony conviction for a nonviolent, general intent drug offense unrelated to voting” should not be considered an “infamous crime,” which under the Iowa Constitution permanently disqualifies a citizen as an elector. She filed suit in November 2014, having been charged and acquitted earlier that year of perjury in connection with voting in a 2013 local election.

Griffin’s lawsuit rests on the Iowa Supreme Court’s plurality opinion in a ballot access case from April 2014. In Chiodo v. Section 43.24 Panel, three justices ruled Tony Bisignano eligible to run for state office despite his prior conviction on an aggravated misdemeanor charge. The plurality opinion further suggested that contrary to a 1994 law defining “infamous crimes” as felonies, not all felony offenses should be considered as such. A concurring opinion held that Bisignano could run for the Senate but warned that the plurality was inviting future litigation from Iowans claiming they should be entitled to vote, because their felony convictions were not for “infamous crimes.” Griffin’s case bears out that prediction.

Polk County District Court Judge Arthur Gamble dismissed her suit last September; excerpts from that ruling are here. The American Civil Liberties Union of Iowa is representing Griffin and appealed. Click here for the full text of the plurality opinion, concurrence, and dissent from the Chiodo case, a key reference point for all of the briefs on Griffin’s appeal. Bleeding Heartland posted highlights from all three opinions.

I’m an ACLU member with a longstanding interest in Governor Terry Branstad’s assault on voting rights. The executive order Branstad issued on his first day back in office created nearly insurmountable hurdles for Iowans convicted of felonies, regardless of the severity of their crimes. The policy also made Griffin, a rehabilitated drug addict and productive member of her community, subject to prosecution over an honest mistake. While Branstad has prevented thousands of Iowans from voting, a disproportionate share of whom are racial minorities, he was happy to let a wealthy, white drunk driver who put others in danger chair a powerful state commission.

In preparation for this week’s oral arguments, I’ve been reading briefs supporting both sides in the Griffin case. The ACLU of Iowa provided copies of the documents, since non-attorneys are unable to access briefs through the Iowa Supreme Court’s website. UPDATE: Ryan Koopmans posted links to all the friend of the court briefs at his blog covering Iowa appellate cases.

I was disappointed but not surprised to see the Iowa County Attorneys Association weigh in for continuing to disenfranchise Griffin (and by extension thousands of similarly situated Iowans). Following an extended discussion of mid-19th century meanings of certain phrases, the brief for the county attorneys warns that “modern understandings” of language from the Iowa Constitution “may easily lead us astray.” Implied but not stated directly: county attorneys know most people would not view a non-violent drug offense as a crime horrible enough to justify a lifetime ban on voting. So they urge the Supreme Court justices to remain bound by what “infamous” may have meant more than a century and a half ago, and leave it to state lawmakers to decide whether to amend current law defining all felonies as “infamous crimes.”

Naturally, county attorneys don’t want justices to use common sense, like a jury did when acquitting Griffin in “less than 40 minutes.” Maybe the Iowa County Attorneys Association should concentrate on educating its members not to make fools of themselves the way Lee County Attorney Michael Short did at Griffin’s trial. Jurors saw through his shouting about a “knowing lie” and the absurd scenario the prosecutor constructed, whereby Griffin somehow stood to gain by deliberately casting an illegal ballot in a non-contested local election.

The Iowa County Attorneys Association brief refers to “our solemn duty to enforce the Constitution and laws of the State of Iowa,” which do not permit Griffin to vote. Maybe the association should focus on educating its members to be more alert to dangerous criminal activity in their jurisdictions. While Short was wasting a court’s time trying to convict Griffin over a misunderstanding, staff at an unregulated boarding school in his county subjected children to abusive discipline practices like isolation boxes on a daily basis. Short recently claimed to know nothing until this January about problems at the now-closed Midwest Academy, even though local “law enforcement [had] received roughly 80 calls to the academy since January 2013,” five of which involved “sexual offense allegations.” The Iowa Department of Human Services “had identified 19 ‘founded’ abuse cases at the school.”

In any event, it’s no surprise the group representing top prosecutors in Iowa’s 99 counties does not sympathize with constitutional claims of an ex-drug offender.

Back to the main point of this post: the Iowa State Association of Counties has asked Supreme Court justices to make the ease of administering elections a higher priority than the fundamental right to vote.

SHORTER IOWA COUNTIES: DON’T MAKE OUR AUDITORS’ JOBS HARDER

Explaining its interest in the Griffin case, Iowa State Association of Counties notes its mission “to promote effective and responsible county government for the people of Iowa,” adding that “County auditors will be on the frontlines of implementing any definition of infamous crimes that comes from this case.” The brief summarizes the association’s primary legal argument as follows:

The election process demands a definition of infamous crime that can be easily discerned and quickly applied. County auditors, as the county commissioners of elections, need a bright-line test in order to be able to provide the public with effective and efficient elections. A test that cannot be swiftly applied in the exact same way in every precinct in our state will have a chilling effect on the entire process – from registration, to voting, to recruiting persons to serve on precinct election boards. Additionally, if the plurality test in Chiodo v. Section 43.24 Panel, 846 N.W.2d 845 (Iowa 2014), or any test that does not clearly set the categories of crimes that constitute infamous crimes, is adopted by the Court, a tremendous amount of litigation will occur to determine what crimes will be categorized as infamous. County auditors will be left in limbo in their attempts to determine who can vote and who cannot vote during the years of ensuing litigation.

Putting “orderly” elections above voting rights

Quoting from District Court Judge Gamble’s ruling in the Griffin case, the brief for county governments argues,

Voting is a fundamental right in Iowa. Chiodo v. Section 43.24 Panel, 846 N.W.2d 845, 848 (Iowa 2014). The State of Iowa has a compelling governmental interest in regulating voting. Id. at 856. However, “any alleged infringement of the right to vote must be carefully and meticulously scrutinized. Statutory regulation of voting and election procedure is permissible so long as the statutes are calculated to facilitate and secure, rather than subvert or impede, the right to vote. Among legitimate statutory objects are shielding the elector from the influence of coercion and corruption, protecting the integrity of the ballot, and insuring the orderly conduct of elections.” Devine v. Wonderlich, 268 N.W.2d 620, 623 (Iowa 1978) (citations omitted).

I wasn’t familiar with the Devine v. Wonderlich case. When I found it here, I saw that Justice Mark McCormick wrote the opinion on behalf of a unanimous Iowa Supreme Court. McCormick has been in private practice since leaving the high court in 1986. He wrote an amicus brief for this case on behalf of the Iowa League of Women Voters, supporting Griffin’s position. Its conclusion:

The right to vote is fundamental. Iowa’s broad restrictions on voting rights are unrelated to Iowa’s stated interest in the integrity or order of elections, and are detrimental to the citizens and communities of Iowa. The Court should find that Iowa’s disenfranchisement policy places an unconstitutional burden on the rights of Iowa citizens, or strictly construe lowa’s disenfranchisement policy to deny voting rights to the fewest number of lowa citizens consistent with valid state goals.

You have to love the irony: the author of Devine v. Wonderlich just wrote a brief urging the Iowa Supreme Court to rule our state’s felon voting restrictions unconstitutional. Meanwhile, the Iowa State Association of Counties relies on Devine v. Wonderlich to contend that the state may infringe on the right to vote, if the goal is to provide for “the orderly conduct of elections.”

The amicus for the counties argues that establishing a new standard for “infamous crimes” would put too many burdens on election administrators.

The Court must drop the nascent prong of the Chiodo plurality test to insure the orderly conduct of elections. Such action will not only insure the continued provision of orderly elections, but will provide security and clarity for persons wanting to vote who have been convicted of crimes.

County auditors cannot be expected to determine at polling places if a crime is one that is “particularly serious” and a crime “that reveals that voters who commit the crime would tend to undermine the process of democratic governance through elections.” Chiodo, 846 N.W.2d at 856. The Court needs to consider the practical realities of conducting elections and institute a bright-line test that auditors and precinct election officials can use when fulfilling their statutory duties. The plurality in Chiodo recognized this was a difficult task. […]

“The concurring justices [in Chiodo] rejected the second element of the plurality’s nascent standard as unnecessary, inconsistent with precedent, and unworkable in the administration of elections.” (Dist. Ct. Order at 10, September 25, 2015; App. 284 (citing Chiodo, 846 N.W.2d at 861) (emphasis added)). ISAC encourages the Court to adopt this opinion and provide county auditors and election officials with a workable and practical definition of infamous crime.

Depicting an expansion of voting rights as “unworkable”

The next section of the brief argues for upholding the current Iowa standard defining all felonies as infamous crimes, because “creating a test that is unworkable in the practical realities of election administration will do a disservice to voters and our election process.” For instance,

Without a bright-line definition of infamous crime, there may be an increase in challenges to voter registrations of persons convicted of crimes that have not been clearly determined by a court as to whether or not they are infamous. This will mean additional administrative burdens on the county and may ultimately discourage people from registering to vote in the first place.

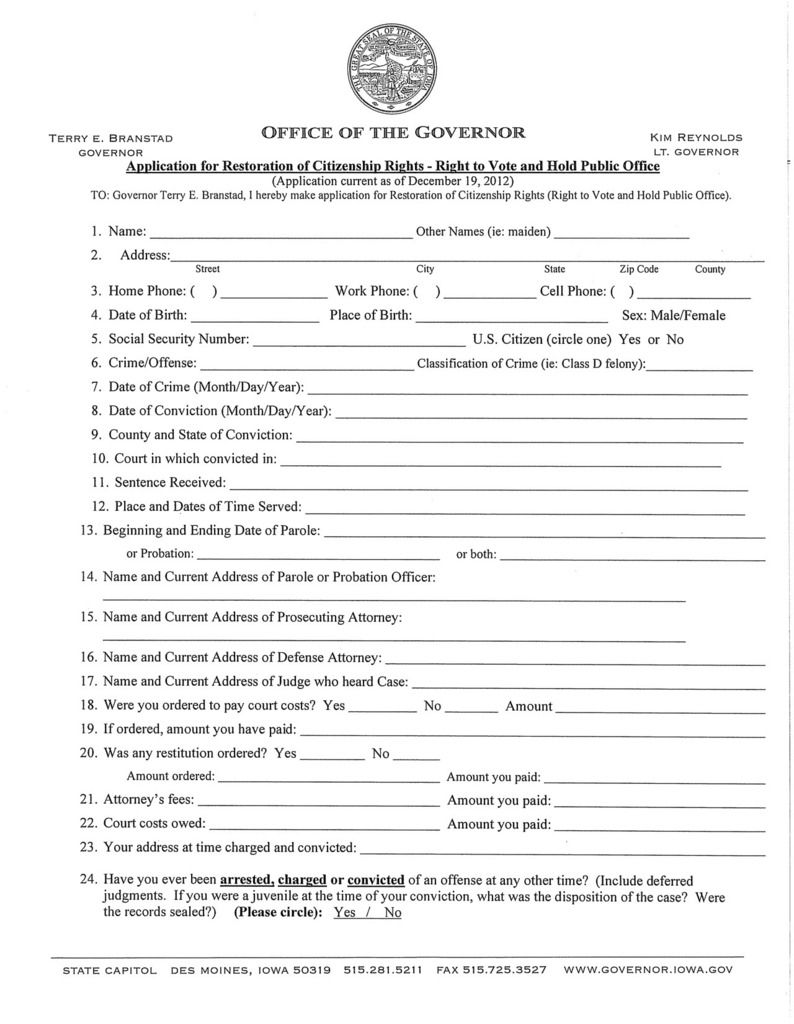

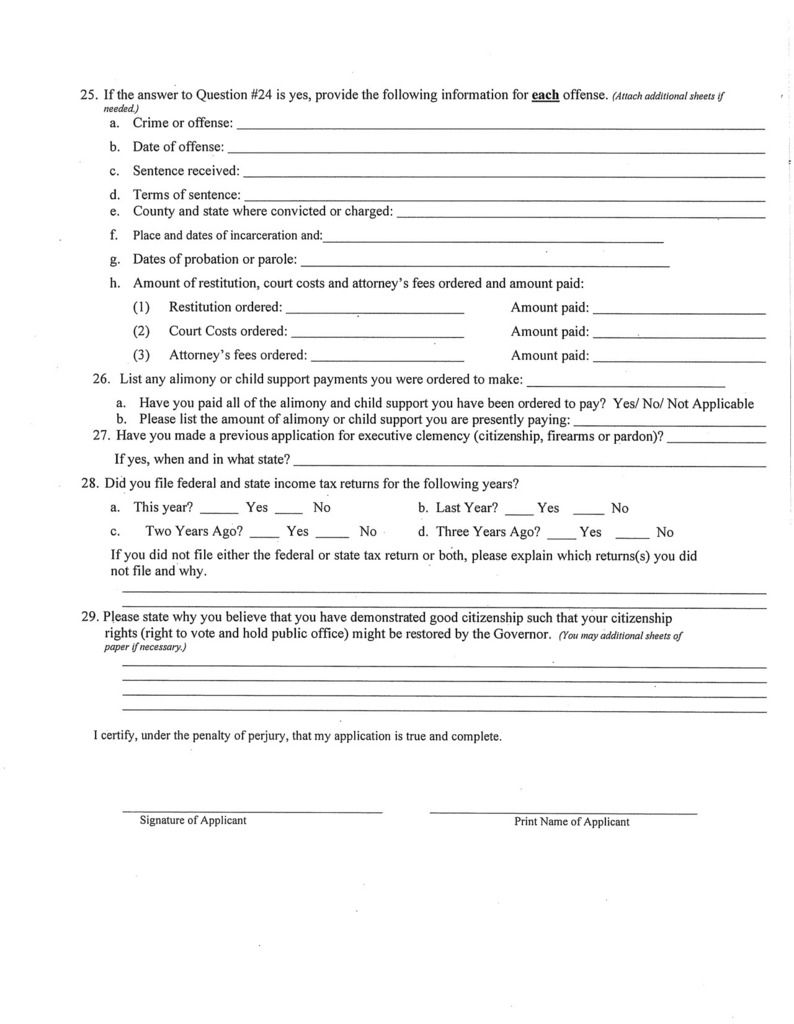

Discourage people more than Iowa’s current process for regaining voting rights? At the end of this post I’ve enclosed the so-called “streamlined” application for having citizenship rights restored. Branstad “streamlined” it in late 2012 by shortening a 31-question form to 29 questions, some of which remain difficult for a person without resources to complete.

The brief points to more challenges when newly-registered voters cast ballots.

Currently, the Iowa Secretary of State maintains a list of persons convicted of felonies and provides that list to county auditors. If the precinct is using electronic poll book laptops, the poll book will tell a precinct election official that the prospective voter is a possible felon. In precincts that are not using electronic poll book tools, the precinct election official has to call the auditor’s office to find out if a new registrant is on the felon list, unless the county provides the felon list from the Secretary of State to each precinct so situated. If those crimes that are infamous are not clearly categorized, it will become extremely difficult, if not impossible, for county auditors to monitor and determine what persons with criminal records are eligible to vote.

Hang on: this brief’s “summary of argument” asserted, “A test that cannot be swiftly applied in the exact same way in every precinct in our state will have a chilling effect on the entire process […].” (emphasis added) Now the county governments tell us that some precincts use electronic poll book laptops, while others do not. So the integrity of Iowa elections doesn’t depend on every poll worker in every precinct performing tasks exactly the same way.

Back to the section on administrative burdens: the brief explains what happens after a voter’s eligibility is challenged at the polling place.

If a person’s qualification to vote is challenged, the person is required to cast a provisional ballot. See Iowa Code § 49.79 (2015); Iowa Code § 49.81 (2015). Then the precinct election official must explain to the person the qualifications to vote and give the person a printed statement explaining the provisional ballot process and the allegations of the challenge. See Iowa Code § 49.81 (2015). The qualifications of all persons filing provisional ballots must be reviewed by the special precinct board after the election, and the board must determine whether to count or reject each provisional ballot. Iowa Code § 50.21 (2015). If the ballot is rejected, the person must be notified within 10 days by the county auditor. Id. Without a bright-line definition of infamous crime, some persons who have been convicted of crimes that have not been clearly included or excluded from the definition, may opt not to attempt to vote for fear of being challenged. When forced to cast a provisional ballot, some will learn only after the official canvass of the election that their provisional ballots were rejected, and then it is too late to have the decision reversed by a court and have the ballot counted.

The county governments posture as being concerned some felons may not try to vote “for fear of being challenged,” or may find out “too late” that their provisional ballots were not counted. To prevent those potential problems, they ask the Iowa Supreme Court to preserve a system that prevents such people from casting ballots for the rest of their lives. Where’s the logic?

Letting more Iowans vote would be a hassle for administrators

In reality, the Iowa State Association of Counties is worried about extra work created for county officials, not about possible burdens on felons who could regain their voting rights if Griffin prevails.

Additionally, there would likely be an increased number of provisional ballots filed and the administration of those ballots would take already scant county resources to process. In 2014, 3,415 provisional ballots were filed in Iowa. […] Between 2012 and 2014, 4,069 persons were removed from the voter rolls in Iowa due to felony convictions. […] Thus, the number of provisional ballots could easily double if it is not clear what felonies are infamous crimes. Each provisional ballot of a person convicted of a crime that is not clearly infamous will need to be reviewed by the special precinct board, the auditor and the county attorney, which will take significant time and delay the election process. The special precinct election board would have more ballots to consider and if faced with an unclear standard to apply, it would likely be harder to recruit persons to serve on these boards.

In other words, the counties want the Iowa Supreme Court to give more weight to potential hassles for precinct election board members than to the fundamental right of Iowans like Griffin to vote.

Mr. desmoinesdem pointed me to this 2012 Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals case, in which the majority of judges struck down the state of Ohio’s limitations on early voting. From page 15:

The State’s proffered interest in smooth election administration must be “sufficiently weighty” to justify the elimination of in-person early voting for non-military voters during the three-day period in question. If the State had enacted a generally applicable, nondiscriminatory voting regulation that limited in-person early voting for all Ohio voters, its “important regulatory interests” would likely be sufficient to justify the restriction. See Burdick, 504 U.S. at 434. However, Ohio’s statutory scheme is not generally applicable to all voters, nor is the State’s justification sufficiently “important” to excuse the discriminatory burden it has placed on some but not all Ohio voters. The State advances only a vague interest in the smooth functioning of local boards of elections. The State simply indicates that allowing in-person early voting, as was done in the past, “could make it much more difficult for the boards of elections to prepare for Election Day.” (R. 35-9, Defs.’ Ex. 8, at 3 (emphasis added).) With no evidence that local boards of elections have struggled to cope with early voting in the past, no evidence that they may struggle to do so during the November 2012 election, and faced with several of those very local boards in opposition to its claims, the State has not shown that its regulatory interest in smooth election administration is “important,” much less “sufficiently weighty” to justify the burden it has placed on non-military Ohio voters.

A Sixth Circuit ruling is not controlling precedent for Iowa (part of the Eighth Circuit). Still, the principle seems relevant to Griffin’s case. If “smooth election administration” is not a compelling reason to stop an Ohio resident from voting early in person, how can it be a compelling reason to deny an Iowan’s right to vote, period?

No one relishes the thought of making county officials’ jobs harder. But frankly, times are tough all over. People who can’t handle the extra work can choose not to run for re-election as county auditor or attorney.

Minimizing future litigation is more important than expanding voting rights

In the next section, the county governments “implore the Court to adopt a definition that will apply to all crimes. To do otherwise, will involve litigation on every individual crime to determine whether or not it is an infamous crime.” That concern loomed large in Justice Edward Mansfield’s special concurrence in the Chiodo case, as well as in the arguments Iowa Secretary of State Paul Pate and Lee County Auditor Denise Fraise submitted to the District Court and Supreme Court in response to Griffin’s lawsuit. The Iowa State Association of Counties warns, “If the Court chooses to rely on the Chiodo plurality test, county auditors, potential voters, and the entire voting process will be in limbo during years of costly litigation.”

To say the “entire voting process will be in limbo” seems like a stretch. The ACLU of Iowa has proposed other standards the Supreme Court could use to establish a new “categorical bright-line rule defining the term ‘infamous crime.'” From page 41 of Griffin’s brief to the high court:

(1) Crimes that are an affront to democratic governance. First, the Chiodo plurality observed that “[s]ome courts have settled on a standard that defines an ‘infamous crime’ as an ‘affront to democratic governance or the public administration of justice such that there is a reasonable probability that a person convicted of such a crime poses a threat to the integrity of elections.’” Chiodo, 846 N.W.2d at 856 (quoting Snyder v. King, 958 N.E.2d 764, 782 (Ind. 2011)). This standard includes only those offenses indicating that the offender is likely to subvert the voting process, such as elections fraud, bribery, and perjury.

(2) Crimen falsi. Second, the plurality observed that other state courts limit the definition of “infamous crime” to “a crimen falsi offense, or a like offense involving the charge of falsehood that affects the public administration of justice.” Chiodo, 846 N.W.2d at 856 (quoting Commonwealth ex rel. Baldwin v. Richard, 751 A.2d 647, 653 (Pa. 2000)). This standard is broader than the first, encompassing all offenses that bear upon a person’s honesty, which includes those described above in category (1), as well as other honesty-related offenses such as forgery, embezzlement, and criminal fraud.

(3) Crimes of moral turpitude. Third, the plurality noted that other state courts establish the standard for infamy as crimes marked by “great moral turpitude.” Chiodo, 846 N.W.2d at 856 (quoting Washington v. State, 75 Ala. 582, 585 (1884)). This standard is the broadest of the three described by the plurality, and encompasses all offenses that could be described as “vile; base; [or] detestable,” Chiodo, 846 N.W.2d at 854 (quoting Snyder, 958 N.E.2d at 780), such as all of the offenses in categories (1) and (2) above, and, in some states, includes other particularly heinous offenses such as arson, rape, and murder.

The Iowa State Association of Counties concludes by asking the Supreme Court to “consider the practical implications alongside the legal theory when adopting a definition of ‘infamous crimes,’ so that the county auditors administering our elections can continue to serve the public by providing efficient and accurate elections.”

But should the efficient working of county election offices be a paramount concern as justices consider acceptable grounds for a lifetime ban on voting? The auditor in Iowa’s most populous county doesn’t think so.

SHORTER JAMIE FITZGERALD: WE CAN DO THIS. LET US DO THIS.

About 14 percent of all registered voters in Iowa live in Polk County, containing the city of Des Moines and most of its suburbs. Census data indicate that the Des Moines metro is “Iowa’s fastest-growing urban area.” So if the Iowa Supreme Court changes the standard for “infamous crimes” that bar citizens from voting, no public official will be more affected than Polk County Auditor Jamie Fitzgerald.

Fitzgerald filed a separate “friend of the court” brief, stating his interest in the Griffin case as follows:

The Proposed Amicus is directly responsible for the management of the election process for roughly 270,500 Iowa voters. The outcome of this action will significantly impact the Auditor’s ability to serve as chief election officer for Polk County, Iowa, and to execute his duties in that role. The Proposed Amicus’ position also clarifies that the positions articulated by other Amici ISAC [Iowa State Association of Counties] and ICAA [Iowa County Attorneys Association] are not ubiquitous among relevant election administrators.

I enclose the Fitzgerald brief in full below. A few passages are worth highlighting.

This is an issue of paramount importance to the Auditor because it impacts the lifetime voting rights of thousands of Iowans in his county. Voting is a fundamental, constitutionally protected right. Devine v. Wonderlich, 268 N.W.2d 620, 623 (Iowa 1978). The right to vote is constitutionally enshrined and cannot be abridged by act of the Iowa General Assembly. See Coggeshall v. City of Des Moines, 117 N.W. 309, 311-12 (Iowa 1908).

Thus, this case is critically important to the people of Iowa and the people of Polk County and the officials elected to represent them. Those officials, particularly those elected to facilitate elections, (namely, county auditors and the Secretary of State) have a duty to facilitate voting in our state by qualified electors. For approximately 100 years, voters in Iowa have been wrongly disenfranchised by the misappropriation of a federal standard announced in Ex Parte Wilson, a case that actually interpreted the Grand Jury Indictment Clause of the Fifth Amendment, not the meaning of “infamous crime” as used by the Iowa Constitution, to disqualify voters permanently from voting in our state. See Ex Parte Wilson, 114 U.S. 417 (1885); Chiodo v. Section 43.24 Panel, 846 N.W.2d 845 (Iowa 2014) (plurality op.).

This case represents the first opportunity for the Court to correct 100 years of bad case law denying voting rights on the basis of any felony conviction. (See Appellant Brief passim.) This Court should reverse the district court below and articulate a rule which disqualifies people only if they have been convicted of a felony that is truly infamous under the Iowa Constitution. As argued persuasively by Mrs. Griffin, this definition does not include nonviolent drug crimes such as the Petitioner’s under any historical standard. (Id.)

Whatever this Court decides, Polk County will feel the impact of the decision more than other counties: Polk County is not only the most populous county in Iowa, it is the most racially diverse. […] Moreover, the harm caused by widespread disenfranchisement to individuals, families, and communities is most severely felt in diverse counties such as Polk County, leading to geographical, socio-economic, and racial swaths of disenfranchised neighborhoods. […]The Court should recognize these harms in looking to adopt the historical definition of the infamous crimes clause most in line with the Iowa Constitution, and should adopt the Affront to Democratic Governance Standard which disqualifies individuals based on the fewest specific felonies. (Appellant’s Br. at 20-30.)

Whereas the county governments plead for a standard that would help auditors run elections efficiently, Fitzgerald makes a powerful statement for other priorities as he asks the high court to “narrowly construe the Iowa Constitution to effectuate broad access to voting in our state.”

Ease of election administration is not the most important concern of a county auditor. The most important concern of the Auditor as commissioner of elections is ensuring that qualified Iowa voters can access the ballot.

As Auditor Fitzgerald understands their argument, amicus ISAC [Iowa State Association of Counties] asks this Court to adopt a bright line test, while remarking that the felon-misdemeanor distinction is a bright line, rather than specifically endorses any particular test. (ISAC Amicus Br. at 2.) Auditor Fitzgerald notes that the Affront to Democratic Governance Test would also provide a bright-line, which would allow auditors to know which specific felonies resulted in disenfranchisement. (Appellant Reply Br. at 25.) However, as the plurality in Chiodo held, the convenience of county auditors is not the primary concern of this case. Nor is it the primary concern of county auditors. Rather, the auditors’ mandate — the auditors’ first duty in holding the office— is the facilitation of elections where all qualified Iowans who properly register and vote are counted so as to ensure the exercise of the democratic process.

Fitzgerald’s brief also notes that election officials manage in states with less restrictive policies on felon voting.

Other states have rules in place that disqualify for some but not all felony offenses, and Iowa could implement such a policy as well. […] For example, eight states disqualify for some specific felonies but not all felonies. Id. Even more states restore voting rights at various stages after conviction.

While county governments depict a standard allowing Iowans like Griffin to vote as “unworkable,” Fitzgerald sees “a number of administrative solutions” for auditors and poll workers. Citing errors in Iowa’s current databases of disqualified voters, which prevented at least twelve eligible voters’ ballots from being counted in 2012, the Polk County auditor argues that

it’s easy to conceive of a similar database that disqualifies based on conviction of specific felonies rather than all felonies, which would likely be easier to administer, if anything, because fewer disqualifying offenses will mean thousands fewer disqualified Iowans on the list to begin with.

In its conclusion, Fitzgerald’s brief rejects the claim that distinguishing people like Griffin from those who have committed “infamous crimes” would create too many problems for elections officials.

Facilitating voting by those persons is not an administrative burden any more than the myriad other provisions that county auditors and poll-workers must contend with. Certainly, it is not insurmountable. Moreover, the Amicus Auditor Fitzgerald welcomes the privilege of facilitating the elections in Polk County in a manner which reverses course on 100 years of faulty disenfranchisement and allows all those qualified to participate in our democracy.

I will be seeking comment from Iowa’s other 98 county auditors on whether the Iowa State Association of Counties or the Polk County auditor has better articulated their views on felon voting rights.

I will update this post as needed to note which auditors stand for keeping tens thousands of Iowans permanently disenfranchised in the name of administrative efficiency, which support expanding the electorate and “ensuring that qualified Iowa voters can access the ballot,” and which refuse to comment on the Griffin case.

UPDATE: The first auditor to respond is Travis Weipert of Johnson County, who says, “I agree 100% with Jamie [Fitzgerald].” Johnson County is Iowa’s fourth-largest in terms of total voter registrations.

SECOND UPDATE: Ryan Koopmans pointed out that two parties that filed amicus briefs will be able to participate in oral arguments, a rare happening for the Iowa Supreme Court:

Griffin is giving five of her thirty minutes to Polk County Auditor Jamie Fitzgerald (who is represented by Des Moines attorney Gary Dickey) and five minutes to the NAACP. Secretary [of State Paul] Pate is giving ten of his thirty minutes to the Iowa County Attorneys Association, which is represented by Muscatine County Attorney Alan Ostergren.

THIRD UPDATE: More auditors have replied to my e-mail seeking comment. From Cass County Auditor Dale Sunderman: “My views are more aligned with those of the Polk County Auditor Jamie Fitzgerald amicus brief […].”

From Boone County Auditor Phillippe Meier:

I definitely agree that this issue needs to be addressed. A definition of what an infamous crime is would be helpful, but so would a standard path for restoration of rights. Since the problem is created by the ambiguity of the Constitution of Iowa, it begs a solution from the legislative or judicial branches of Iowa government.

I would like to be part of the solution on this issue, as it is difficult to assist residents who believe that they have paid all their debt to society by successfully completing probation, and paying all restitution and they never hear a decision on their application to re-instate rights.

Black Hawk County Auditor Grant Veeder sent this response:

Thank you for the opportunity to comment on your article about the amicus briefs filed by the Iowa State Association of Counties and Polk County Auditor Jamie Fitzgerald in Griffin v. Pate and Fraise.

You quote the portion of the ISAC brief that says, “Each provisional ballot of a person convicted of a crime that is not clearly infamous will need to be reviewed by the special precinct board, the auditor and the county attorney, which will take significant time and delay the election process. The special precinct election board would have more ballots to consider and if faced with an unclear standard to apply, it would likely be harder to recruit persons to serve on these boards.” You feel that it necessarily follows that “[i]n reality, the Iowa State Association of Counties is worried about extra work created for county officials, not about possible burdens on felons who could regain their voting rights if Griffin prevails.” I disagree.

It is true that if there is no bright line of definition for infamous crimes, election administration will become more difficult. But that doesn’t mean that the only argument for it is to make things easier for county auditors. Speaking for myself and I believe many others, I have very real concerns about the lack of consistency that would result from attempting to individually evaluate the status of every voter with a felony conviction. As the ISAC brief says elsewhere, “County auditors cannot be expected to determine at polling places if a crime is one that is ‘particularly serious’ and a crime ‘that reveals that voters who commit the crime would tend to undermine the process of democratic governance through elections.’ Chiodo, 846 N.W.2d at 856.”

In another article (April 15, 2014), you discuss Justice Mansfield’s concurring opinion in Chiodo as follows: “However, Mansfield would have accepted the bright-line definition from the 1994 state law, equating felonies with ‘infamous crimes.’ He warned that the plurality opinion would serve as a ‘welcome mat’ for future litigation from felons claiming that they should be entitled to vote, because their convictions were not for ‘infamous crimes.’ On balance, I agree most with Mansfield’s opinion.” If you believe that a bright-line definition is desirable, you and I are in agreement.

County auditors would certainly wish to avoid future litigation for themselves, but they also worry about the involvement of other election officials. In a busy election, precinct election officials may not be able to consult with their county auditors in all cases involving possible infamous crimes. Forced to make a decision on their own, they may decide that the voter is entitled to vote a regular ballot, or they may decide that the voter should vote a provisional ballot. The safest path is to require a provisional ballot in any doubtful case. This may unnecessarily impede eligible voters in the exercise of their franchise.

Provisional ballots are considered by the Absentee and Special Voters Precinct (ASVP) board two days after the election. However much the auditor may provide evidence or recommendations, the final decision on whether a provisional ballot counts is legally in the hands of the precinct election officials of the ASVP board (see Code of Iowa §50.22).

Precinct election officials, ordinary citizens who perform this service maybe twice a year, are unlikely to act with complete consistency in these cases, either at the polls or on an ASVP board. As Justice Mansfield suggests, litigation would probably follow any actual or perceived inconsistency between counties, between precincts, or even within precincts. I don’t know if precinct election officials would be directly liable in any lawsuit, but simply to be involved and to have their judgment and integrity questioned, or to have to hold that possibility in contemplation, would be a deterrent on their serving in future elections.

Please allow me to express my personal opinion about Iowa law concerning infamous crimes and felony convictions. It appears there can be no progress in this regard unless the Iowa Constitution is amended. I believe it should be amended for better clarity, and to allow a more humane exercise of voting rights. I agree with Auditor Fitzgerald that the Court “should articulate a rule which disqualifies people only if they have been convicted of a felony that is truly infamous under the Iowa Constitution.” I believe that Iowa should be like most states in the Union and allow “infamous” felons who have complete their sentences to vote, without a lengthy and difficult restoration-of-voting-rights process.

It is unfortunate that two points of view with so much in common have to oppose each other in the limited scope of an individual lawsuit. Auditor Fitzgerald, while quite rightly emphasizing that “[e]ase of election administration is not the most important concern of a county auditor,” also addresses the importance of that issue when he says that “it’s easy to conceive of a … database that disqualifies based on conviction of specific felonies rather than all felonies, which would likely be easier to administer, if anything, because fewer disqualifying offenses will mean thousands fewer disqualified Iowans on the list to begin with.”

I believe that a bright line definition is needed to avoid a dangerous inconsistency in the application of the law, which is the crux of the ISAC brief, and for which you have evidenced some support. I also believe, along with Auditor Fitzgerald, that Iowa should have more progressive laws regarding the exercise of the franchise, and that Iowans who have fulfilled the terms of any legal punishment should not be prevented or discouraged from voting.

The following auditors responded with “No comment”: Floyd County Auditor Gloria Carr, Buchanan County Auditor Cindy Gosse. UPDATE: Also declining to comment: Muscatine County Auditor Leslie Soule, Humboldt County Auditor Peggy Rice, Plymouth County Auditor Stacey Feldman, Decatur County Auditor Stephanie Daughton, Franklin County Auditor Michelle Giddings, Butler County Auditor Liz Williams, Osceola County Auditor Barb Echter, .

LATE UPDATE: Clinton County Auditor Eric Van Lancker responded, “I did appreciate Auditor Veeder’s clarification of the ISAC position. But with that said, I agree with Auditor Fitzgerald’s position on the matter.”

Linn County Auditor Joel Miller responded, “I agree with Auditor Fitzgerald and I appreciate his filing of a brief with the Court.”

Hardin County Auditor Jessica Lara responded,

Iowa’s history of not allowing those convicted of infamous crimes to vote is not so cut and dry as it seems. First, infamous crime needs to be defined as it has changed in context over the years. At one time, some serious misdemeanors were included along with all felony convictions in denying voters the right to vote. Then it was only certain felonies, not all. I’m not even certain I know what would constitute “infamous” now as it seems to change over time.

More confusing in this matter is whether rights have been restored or not. It used to be a burden placed upon the convicted felon to seek to have rights restored. There were steps to be taken, processes to be completed. Certificates of these rights being restored were issued to those successful in restoration. Then Former Governor Vilsack signed Executive Order 42 which restored rights to ALL convicted felons if their sentences were discharged on or before July 4, 2005. No certificates were issued. This is when the issue of whether felons can vote or not really became cumbersome to Auditors. “Were you convicted and had your sentence discharged prior to July 4, 2005?” “If after July 4, 2005, have you had your rights restored?” “Do you have a certificate proving your rights were restored?” “Your name still appears on the convicted felon list. You’ll have to vote provisional.”

I was a supporter of voting rights being terminated upon conviction of a felony. However, after the last Presidential election, I changed my opinion based on personal experience. I had a female voter who attempted to vote on Election Day. Our electronic poll book alerted her that she was a possible match to the convicted felon list. She wanted to vote anyway, insisting that her rights had been restored. Her conviction was after 2005, so the blanket Executive Order did not apply. She did not have a certificate, nor had she ever received one, so I was unable to prove her rights had been restored. Throughout the confusion of this process, she was incredibly patient and polite. She could have easily given up in frustration, but she chose to stay. It was that important to her that she vote. After casting a provisional ballot, she was grateful for my assistance. The following day, her attorney was able to fax over documentation of her right to vote and her provisional ballot was counted. This process was time consuming and in my opinion unnecessary, not to mention degrading and embarrassing to the voter.

Having Auditors check a data base (list) that is full of errors is not a good method for validating whether a person should be voting or not. In the above case, her name was on that list. I further checked with the SOS office on Election Day, and was told she was not eligible to vote unless she voted provisional. However, the following day it was proven that she was eligible. This is not a good way to conduct elections. The statewide database has been proven to be outdated as well as littered with errors. It is my opinion that regardless of the conviction, if the sentence has been served and discharged, the right to vote should be an automatic reinstatement. I think it would simplify the process of voting, not hinder it.

As an administrator of the election process, I adhere to code, rules, and policy to verify that I am conducting the most fair and impartial election possible. I cannot honestly say that when faced with a convicted felon. I have no idea whether or not they can legally vote. I cannot trust the data base. There are too many “ifs”, “whens,” and “hows.”

This doesn’t give a straight-forward answer as to which viewpoint more closely aligns with mine. I draw from both. I do want a hard/fast rule that is easy to apply. (ISAC) I don’t think that redefining “infamous” will create undue hardships on Auditors. (Fitzgerald). How about we seek to fix the problem/issue rather than keep redefining the term that creates the problem in the first place. Let’s revisit why we are denying convicted felons the right to vote. Aren’t we one of only a handful of states that deny felons?

I am always happy to discuss the procedures involved in conducting elections in my jurisdiction, and appreciate your inquiry.

1 Comment

Well Done

Great article, DesMoinesDem. Gives a great understanding of the issues at hand. Well done.

JoshHughesIA Mon 28 Mar 9:25 AM