Governor Kim Reynolds restored voting rights to 35 Iowans during her first year in the state’s top office. That number represents less than one-tenth of 1 percent of at least 60,000 Iowans who are ineligible to vote due to a felony conviction. Just 241 Iowans–less than one-half of 1 percent of those disenfranchised–have regained their voting rights since Governor Terry Branstad changed the system seven years ago to require a cumbersome application process.

Iowa is one of only four states that disenfranchise felons for life. Our state constitution denies voting rights to all persons “convicted of any infamous crime,” and a 1994 law defines all felonies as infamous crimes.

At least 115,000 Iowans regained their voting rights during the five and a half years after Governor Tom Vilsack created an automatic process for reviewing files of offenders who had completed felony sentences. But Branstad issued a new executive order on his inauguration day in 2011, forcing offenders to apply for a voting rights restoration.

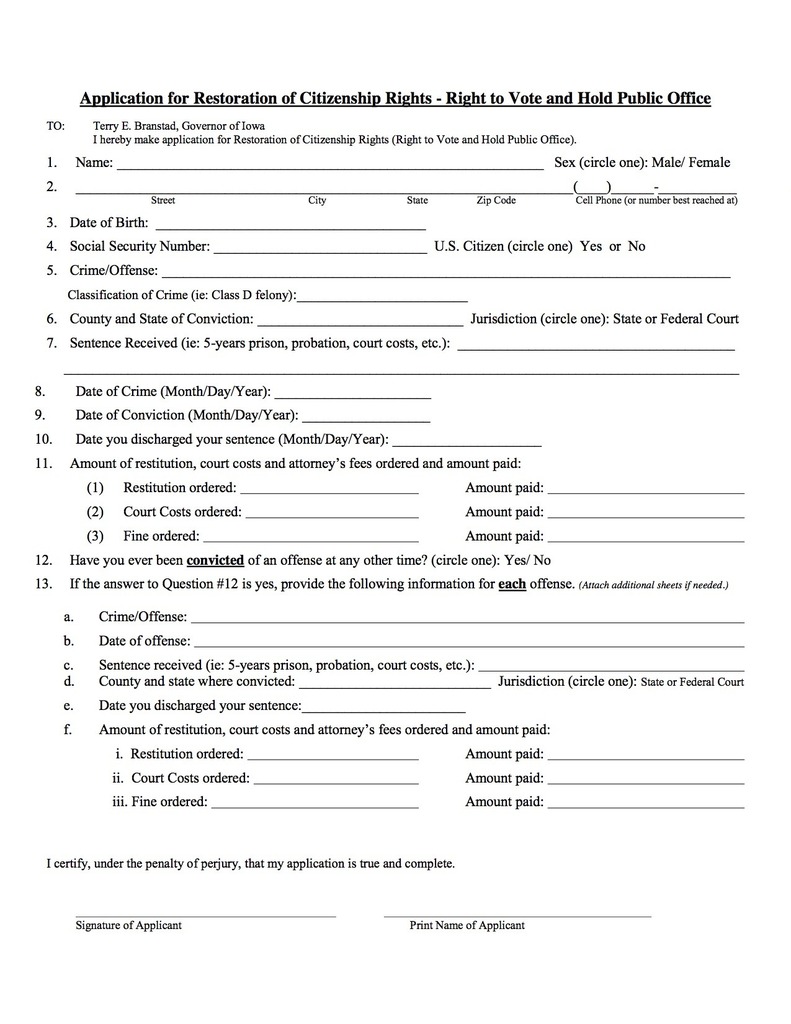

Two years ago this week, a divided Iowa Supreme Court upheld that system as consistent with our state’s constitution. While the case was pending, Branstad “streamlined” the voting rights application for a second time. However, only a small fraction of offenders attempted to navigate the process. Applicants must collect a number of documents and prove they have paid all court costs, fines, and restitution. (Scroll to the end of this post to view the current form.)

From January 2011 through the day Branstad resigned as governor to become U.S. ambassador to China, he restored voting rights to only 206 people.

According to the Iowa Secretary of State’s office, 67,389 names were listed in the felon database as of June 20, 2018. Taking into consideration people who no longer live in Iowa and some duplicates (Bob Smith and Robert Smith, or John Doe and John Paul Doe), at least 60,000 and perhaps as many as 65,000 Iowans are ineligible to vote because of a felony conviction.

Colin Smith has helped process many voting rights restoration applications as legal counsel to Branstad and Reynolds. Responding to my request for statistics covering May 24, 2017 (when Reynolds took the oath of office) through May 25, 2018 (the pre-registration deadline for Iowa’s primary election), Smith said 35 people regained the right to vote during that period. He noted,

This number exceeds the number of voting rights restoration grants completed during the first year of the previous administration. This number of voting rights restoration grants also exceeds the number of total restoration grants in five out of the last six years (the one year not exceeded being 2016, a year involving the Iowa caucuses and a competitive presidential election). This number also does not include the restoration of rights for 11 additional individuals that occurred in 2017 prior to the gubernatorial transition (January 1, 2017 to May 24, 2017). In short, this number is in line with — and exceeds — what one would expect for voting rights restoration applications in an odd year before a statewide election year.

In other words, Iowans should expect that only a few dozen people each year will regain a fundamental constitutional right under a system Branstad characterized as “simple,” “efficient,” and “convenient.”

Smith noted, “No eligible individual who has submitted a completed voting rights restoration application has been denied” since Reynolds took office. In addition, fourteen applications are pending and will be granted if the Division of Criminal Investigation confirms the information provided. The governor’s staff are “working with” a few other people who submitted incomplete applications during the past year.

Thousands of people complete felony sentences every year in Iowa, many for non-violent crimes that stemmed from a substance abuse or addiction problem. One long-range study “found on average 30% of felons and ex-felons would vote if given the chance.”

The governor’s communications staff have ignored my repeated follow-up inquiries:

• Does Reynolds think it’s appropriate for 99.95 percent of Iowans who have committed a felony offense to remain unable to vote for the rest of their lives?

• Does the governor believe the 0.05 percent who make it through the restoration process are the only people with felony convictions who deserve to vote?

• Why wouldn’t the governor want to encourage full civic participation by more people who have served their time and are getting their lives on track?

• Would the governor consider executive action to lower the barrier for past offenders to participate in political life again?

• Is acting Lieutenant Governor Adam Gregg, who formerly served as state public defender, satisfied that thousands of Iowans lose their voting rights each year and less than 1 percent get them back?

Reynolds could open the door for thousands of Iowans with a new executive order instructing the Department of Corrections to regularly send her office the names of those who have completed prison terms, probation, and parole. The governor’s staff could review the list to identify who has paid all applicable fines, court costs, and restitution. Then Reynolds could restore voting rights to all who meet the criteria.

Taking a further step toward fairness, the governor could ditch what is tantamount to a poll tax and declare that money will no longer determine whether Iowans can exercise a fundamental constitutional right. As things stand, two people may commit the same crime, but the one with plenty of cash will have an opportunity to vote again, while the one barely getting by will never be able to cast another ballot. Many people who are rebuilding their lives after a felony conviction can’t spare several hundred dollars to cover court costs or fines.

Reynolds has spoken publicly about overcoming addiction and has cultivated an image as someone who understands the struggles of working-class Iowans, thanks to her humble roots. Last year she told a group of women receiving high school equivalency diplomas while incarcerated “not to let their time in prison define them, and to use their education to make better decisions when they return to society.” The governor could walk her talk by bringing Iowa in line with most other states, so a crime committed in the past won’t forever define 99.95 percent of offenders as unable to vote.

Appendix: Voting rights restoration application, taken from the governor’s website. At this writing, the form still lists Branstad as governor and Reynolds as lieutenant governor.

1 Comment

Thank you

Thank you for digging into this. Govenors Reynolds and Branstad should be ashamed of themselves for this punitive policy. Hopefully we will have a new governor soon that will reverse it.

JeffDC Thu 28 Jun 2:11 PM