Republican lawmakers and Governor Kim Reynolds are poised to give GOP officials and their proxies control over what has been a mostly non-partisan system for choosing Iowa judges since 1962.

Until a couple of months ago, I didn’t realize the Republican trifecta could blow up our judicial selection process in a matter of weeks. The Iowa Constitution spells out how vacancies on the bench are filled, and altering any language in our state’s founding document takes years.

Unfortunately, a time bomb has lurked in Article V, Section 16 for more than five decades. While most elements of the system can be changed only through a constitutional amendment, the manner of forming judicial nominating commissions (half appointed by the governor, half elected by attorneys) is specified only “Until July 4, 1973, and thereafter unless otherwise provided by law.”

How did that language end up in the constitution? A Linn County Democrat offered a fateful amendment 60 years ago.

“A COMPETENT AND STABLE JUDICIARY IS VITAL TO OUR POLITICAL EXISTENCE”

Enacting Iowa’s merit-based system was a strange political development in some respects. When lawmakers started the process of amending the constitution in 1959, the GOP controlled the state House and Senate. Although Governor Herschel Loveless was a Democrat, Republicans had occupied the governor’s office for much of the previous century. Most statewide elected officials were Republicans, including seven of nine Supreme Court justices. Most Iowa District Court judges elected in 1956 or 1958 were Republicans as well.

Why would Republicans do away with judicial elections they were mostly winning?

The Iowa Supreme Court recommended a package of reforms to improve the courts in January 1959. The fifth point made the case for amending the constitution.

1. Selection and Tenure of Supreme and District Court Judges. A competent and stable judiciary is vital to our political existence. Any judicial system is only as good as its judges. The best judicial system is the one which attracts and retains the most capable judges. The increasing complexity of our civilization demands the highest judicial capacity. It is even now becoming most difficult to induce capable men to accept judicial office for the following reasons:

a. Men competent to be judges are reluctant to surrender the security of their established practices for judgeships which may be terminated by a political election involving issues totally unrelated to judicial ability and service.

b. Judicial salaries have not kept pace with the cost of living and are unrealistic.

c. Present judicial retirement benefits are inadequate.The judges of the Federal courts are appointed by the President and the judges of many state courts are appointed by the Governors. From a study of the plans of court reorganization and the experience of other states, we find the best method of selection of judges to be their appointment by the Governor from nominees submitted to him by nonpartisan nominating commissions.

The Supreme Court justices suggested a constitutional amendment much like the version lawmakers eventually passed in 1959 and 1961 and voters approved in 1962. The governor would gain the power to appoint judges, but would be required to select a candidate from a short list provided by a judicial nominating commission. The governor would appoint half the members of the State Judicial Nominating Commission and similar panels in districts around Iowa, and attorneys would elect the other half.

FRACTURED COALITIONS

Many Iowa lawmakers resisted giving up judicial elections or objected to other elements of the high court’s solution. State senators considered and rejected several amendments during two Iowa Senate debates in February 1959, passing the proposal by 31 votes to 19. There was no consensus in either caucus; 22 Republicans and nine Democrats voted yes, while eleven Republicans and eight Democrats voted no.

The Iowa House was in no rush to pass Senate Joint Resolution 7. When the lower chamber finally took up the constitutional amendment in early April, a Republican lawmaker offered a sweeping amendment removing all references to judicial nominating commissions and appointments by the governor. Under his plan, the legislature could have changed how judges were selected at any time. That idea lost by a large margin, 73 votes to 26.

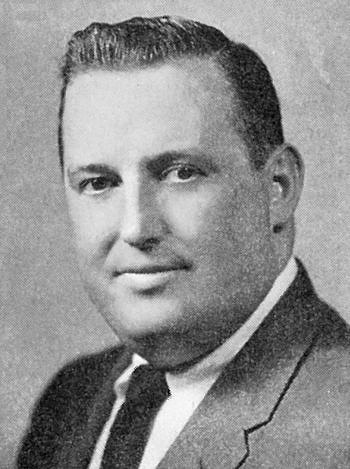

Then Frank Martin, a young attorney and first-term Democrat from Cedar Rapids, offered a narrowly-focused change.

Amend Senate Joint Resolution 7 as follows:

1. By inserting after the period (.) in line twenty-one (21) the following: “Until July 4, 1973, and thereafter unless otherwise provided by law, the State Judicial Nominating Commission shall be composed and selected as follows:”

2. By inserting after the period (.) in line thirty-four (34) the following: “Until July 4, 1973, and thereafter unless otherwise provided by law, District Judicial Nominating Commissions shall be composed and selected as follows:”

At the time, Republicans held 60 House seats and Democrats 48. (The Iowa House had 108 members before a 1968 constitutional amendment reduced the chamber to its current size of 100 representatives.) Both caucuses were divided on Martin’s amendment. It passed by 54 votes to 46, with 28 Republicans and 26 Democrats voting in favor and 25 Republicans and 21 Democrats voting against.

The two Iowa House Republicans from that era whose names will be most familiar to Bleeding Heartland readers split: State Representative David Stanley backed the Martin amendment, while fellow first-termer Chuck Grassley was one of the the “nays.”

Grassley offered his own amendment, which would have allowed judges to hold other offices immediately after leaving the bench. It lost by a large margin.

Then Stanley moved final passage of the constitutional amendment, which House members approved by 57 votes to 50. Fourteen Democrats (including Martin) joined 43 Republicans (including Grassley and Stanley) to approve the changes, while 33 Democrats and seventeen Republicans voted against the new judicial selection plan.

Because the House had altered the wording, Senate Joint Resolution 7 went back to the upper chamber. One Republican senator offered his own amendment, which would have allowed lawmakers to change the rules on judicial nominating commission members at any time, not just after July 4, 1973. It failed by 27 votes to 22.

The Senate then concurred in the House amendment and approved the joint resolution by 30 votes to 16. Again, both caucuses were divided: nineteen Republicans and eleven Democrats voted for the reforms, while eleven Republicans and five Democrats opposed them.

Changing Iowa’s constitution requires two separately-elected legislatures to approve identical amendments, so the judicial selection plan came back to the legislature in February 1961. By that time, Republicans had increased their ranks in both chambers. Democratic Governor Loveless ran unsuccessfully for U.S. Senate instead of for re-election in 1960, and Republican Norman Erbe now occupied Terrace Hill, which may have reassured reluctant GOP lawmakers about the kind of judges who would be appointed under the new system. Consensus was building in favor of the changes, though some members of both parties continued to resist.

State senators voted down a series of proposed amendments before approving the same language that cleared the chamber two years earlier. The vote on final passage for what was now called Senate Joint Resolution 14 was 40 to 10, with 28 Republicans and twelve Democrats in favor and six Republicans and four Democrats against.

Three weeks later, the Iowa House approved the constitutional amendment by a comfortable 85 to 22 margin. Sixteen Democrats joined 69 Republicans (including Grassley and Stanley) to vote “yea,” while thirteen Democrats and nine Republicans were “nays.”

The final step in amending Iowa’s constitution is a statewide vote. The judicial selection proposal appeared on the June 1962 primary ballot, where it passed by 158,279 votes to 118,215 (57.2 percent to 42.8 percent).

We can only guess why Martin offered his amendment; he died in the summer of 1959. Since he was a lawyer who supported the idea of merit-based selection, he probably wasn’t against giving elected attorneys half the seats on judicial nominating commissions. Rather, dangling the prospect of remaking the commissions by law someday may have been a tactic to bring opponents around. Remember, the constitutional amendment cleared the Iowa House in 1959 with only a few votes to spare.

Arguably, it was reasonable to gamble that by 1973, when the new system had been in place for a decade, there would be little appetite for changing it. Indeed, Republicans didn’t attempt to pack the courts when they had trifectas in the 1970s (under Governor Bob Ray) or the 1990s (under Governor Terry Branstad). Nor was judicial selection debated when Democrats controlled the legislature during Governor Chet Culver’s term (2007 through 2010).

Our current governor isn’t constrained by the rule of law. Reynolds has shown she will ignore a constitutional requirement, or the letter or spirit of a statute, if she sees a political advantage in doing so. No one should be surprised she is eager to seize control over judicial selection, an issue she never raised while running for office last year.

Iowans will be worse off after Republicans put politicians fully in charge of picking judges. In all likelihood, removing elected attorneys from the process isn’t what Representative Frank Martin had in mind when he offered that amendment 60 years ago. Unintended consequences can be profound.

LATE UPDATE: The final version of the bill to change Iowa’s judicial selection system, which Republicans approved on the last day of the 2019 legislative session, preserved a role for elected attorneys on nominating commissions.

Appendix 1: Text of proposed constitutional amendment approved by both the Iowa House and Senate in 1959, including amendments lawmakers offered during debate.

Appendix 2: Text of proposed constitutional amendment approved by both the Iowa House and Senate in 1961, including amendments lawmakers offered during debate.

Appendix 3: Recommendations for improving Iowa’s judicial system, which the Iowa Supreme Court submitted to state lawmakers in January 1959.

Appendix 4: Notes and roll call votes from the first Iowa Senate debate on changing judicial selection in 1959.

Appendix 5: Notes and roll call votes from the second Iowa Senate debate on changing judicial selection in 1959.

Appendix 6: Notes and roll call votes from the Iowa House debate on changing judicial selection in 1959.

Appendix 7: Notes and roll call votes from the third and last Iowa Senate debate on changing judicial selection in 1959.

Appendix 8: Notes and roll call votes from the Iowa Senate debate on changing judicial selection in 1961.

Appendix 9: Notes and roll call votes from the Iowa House debate on changing judicial selection in 1961.

Top image: State Representative Frank Martin’s official legislative photo from 1959.

5 Comments

Stacking the Court is Wrong!

What an amazing piece of journalism! Laura, thanks for the hard work digging out the history of that odd language. Who ever heard of a constitutional provision saying, in essence, this is the way it will be, unless the Legislature changes it ….. ? I could hardly believe it when I read it the other day, but there it is.

This bill may be the worst of all the radical moves by Iowa Republicans since they obtained “the trifecta.” While awful, the other changes did not assault the checks and balances between Iowa’s three branches of state government. This latest bill does precisely that. It is a stark assault on the independence of the judiciary and it is wrong! It injects politics into the judiciary in a way that Iowa has not experienced for nearly 60 years.

Iowa has two policies that place it above the nation in the way of good government; our non-partisan redistricting process and our judicial nominating process. We truly are the envy of the nation in those two areas. While so many of us were concerned the R’s would go after redistricting, we didn’t anticipate this attack on the judiciary. What goes around comes around, and they will someday be on the other end of this if they pass this. On the other hand, Democrats are so civic-minded that we’ll likely change it back when we have the chance to do so, and I’d hope that day would come sooner than later as this change will almost certainly send Iowa back to a time when the fairness of the judiciary was in question.

billbrauch Fri 8 Feb 9:40 AM

all these years

It’s been hiding in plain sight in the constitution. I had no idea they could change any element of the system through a law.

Far more Republicans than Democrats serve on judicial nominating commissions, but that’s not good enough for today’s GOP. It’s a real tragedy that will lead to less qualified and more overtly partisan judges, which is the norm for many states.

Laura Belin Fri 8 Feb 4:37 PM

Hindsight is 20/20...

…of course. But hasn’t there been a time in the last forty years when Democrats controlled enough of state government that the time bomb could have been defused?

PrairieFan Fri 8 Feb 5:57 PM

the only time Democrats had the trifecta

was from 2007 to 2010. I don’t think it occurred to anyone that the current scenario was a possibility. Very few people (including myself) had any idea this loophole was in the constitution.

Laura Belin Sat 23 Feb 8:50 PM

History

This is fascinating. I served on the Judicial Nominating Commission and knew nothing of this history. What a great piece of journslism.

birminghan1@aol.com Fri 11 Feb 3:53 AM