John Norwood is an elected commissioner of the Polk County Soil and Water Conservation District. -promoted by Laura Belin

On the evening of February 27, your Soil and Water Commissioners for Region 6 (including Polk, Dallas, and Madison Counties) gathered for our Spring Regional meeting in Winterset.

We heard from a variety of state and federal partners and discussed staffing, funding, and priorities for improving our soil health and water quality.

WATER QUALITY IS A FUNCTION OF CULTURAL PRACTICES, SOIL HEALTH AND APPROPRIATE INFRASTRUCTURE

Water quality strategies include installing conservation infrastructure like CREP-style [Conservation Reserve Enhancement Program] or Tile area wetlands, edge of field solutions like saturated buffers, and utilizing and integrating cover crops into a long-term program for building soil structure.

Soil structure refers to

the arrangement of soil separates into units called soil aggregates. An aggregate possesses solids and pore space. Aggregates are separated by planes of weakness and are dominated by clay particles. Silt and fine sand particles may also be part of an aggregate.

Essentially, structure is what enables our soils to perform a variety of important biological and physical functions including its capacity to hold and retain nitrogen and other nutrients. With respect to building organic nitrogen in our soils, it’s a process which can take ten years to improve the organic nitrogen content by 1 percent.

However, over the longer term, productivity benefits from healthier soils can be significant according to the USDA presentation given last evening. When healthier soils are combined with cover crops and other cropping and livestock strategies, ROI [return on investment] levels can exceed 200 percent, as we learned from several pro forma examples discussed.

We also learned last evening that according to regional soil health specialists with the USDA, we are losing an average of 50 to 60 pounds of nitrogen per acre per year in Iowa because of factors like poor soil health and historic agronomic practices that exacerbate surface compaction. This in turn causes water to run across the soil surface vs. infiltrating into the soil. What’s the result?

Excess nitrogen is finding its way into our rivers and streams and costing both society and producers. For producers, the loss is $19 to $38 per acre! Multiply those per acre figures by the 23 million acres we farm to row crops, about 12 million is tiled, 6 million within critical drainage district control, and you begin to get the picture in terms of lost dollars and tons of nitrogen moving down our streams and rivers.

THERE IS HOPE! BUT “CULTURE EATS STRATEGY FOR BREAKFAST” UNLESS WE CAN HARNESS THE CULTURE TO CREATE THE CHANGE WE DESIRE

With cover crops and cover cropping strategies that offset the cost of planting cover crops, we can begin to drive economic value of cover crops in livestock and cropping systems while we build soil health and improve water quality. However, there is a catch. Human behavior! Trying something new and operating differently requires new thinking. And many of us, myself included, can get set in our ways. Farming is one of the most culture driven industries that I can think of.

My takeaway from yesterday’s workshop: For the cover crop strategy, we need a human led/farmer led mentoring program to accelerate the learning and adoption of these practices and strategies. Farmers pay attention to what other successful farmers are able to do, particularly if it favorably impacts the bottom line. We also need to align financial incentives, encourage buying groups to buy down cover crop installed costs, and begin to underwrite certain risks to get more landowners, more quickly up the learning curve and implementing, successful cover cropping programs.

AN ENGINEERING CHALLENGE FOR TODAY’S GENERATION

As part of this larger effort to improve our soil health and water quality, a major drainage/water management engineering challenge lies before us. Something on the order of tens of millions of dollars per year of new investments in rural Iowa. Why?

Because our tile drainage systems, some which are over 100 years old, were never designed to manage water beyond getting it off the field as quickly as possible. These systems need to be re-engineered and modernized to manage water. Hence, we need to dramatically increase our investments in conservation infrastructure like tile area wetlands that are used to filter tile water that is collected, often from multiple landowners.

COSTS NEED TO BE PUT IN CONTEXT WITH COSTS AND BENEFITS UNDERSTOOD

I often hear at the policy level, even from sympathetic legislators, that a $625,000 tile area wetland cost is too expensive. This happens, usually, without the legislator or stakeholder fully understanding how to place that cost in perspective, given the area it serves and how it compares to other public investments we make.

For example, we are spending $30 million each for two highway “flyovers” (Ames and Grimes) to save commuters, what, five minutes of travel time during the work week? Yes, that’s mostly federal money, but a cost that is borne by taxpayers nevertheless.

When we look at the cost of a $625,000 tile wetland, otherwise known as “conservation infrastructure”, first consider it is a 100- to 125-year asset. Second, think about its cost relative to the acreage served. On a per acre cost, that wetland will treat 2,000 to 4,000 acres, or about $150 to $300 per acre over the life of that asset. Over its useful life, the cost per acre per year is more like $1.50 to $3.00.

Now, consider farmers are investing $100, $200 to $300 per acre to add new pattern tiling to improve their lands productive capacity. We can begin to see that the cost of the conservation infrastructure is quite reasonable when placed in context of our public and private investment.

CONSERVATION INFRASTRUCTURE PROVIDES FINANCIAL AND ENVIRONMENTAL BENEFITS

Some of our conservation infrastructure programs, such as the CREP eligible wetlands and similar programs, are designed to make the producer whole financially while providing new sources of farm income that diversifies the ups and downs of corn and bean prices. These are critical points and important ones to consider in designing an economic framework for our farmers that will promote more diversity, resiliency, and stability in the face of increasing volatility and market risk, trade risk, weather risk, insect risk, etc.

The beauty of this conservation infrastructure is that it also provides a stream of environmental benefits including wildlife and pollinator habitat, hunting ground, recreational opportunities and water quality filtering which includes pathogen control from manure derived nutrients.

CONSERVATION INFRASTRUCTURE IS AS IMPORTANT AS ROAD AND SEWER INFRASTRUCTURE

In summary, we need to begin to think about our agricultural conservation infrastructure on a par with the importance of other critical public infrastructure like public treatment works and public roads. Which is more important to you? Good roads or safe water to drink, swim, fish? I would argue both are vital to our health and long-term survival. But we fund one with millions of dollars annually using a dedicated funding source while we expect the other to flourish using a hodge-podge of anemic funding sources. We lull ourselves into thinking we can address the job with the equivalent of a fraction of the necessary funds, cost-share, “bake sales,” and the like.

This thinking needs to change. We need to make our conservation infrastructure to be a public health and agricultural productivity priority in this state.

We also need to be more strategic in how and where we make the investments with a focus on ROI, addressing the cultural challenges of driving change, and we need to build the capacity to get the job done in a reasonable period of time. This can’t be a strategy of everyone for themselves, or a farm-by-farm approach since drainage water often crosses property lines and political boundaries. We need collective action and collaboration action with our drainage districts, county, state, and federal government agencies and University experts. We have good people to get the job done.

I estimate it’ll take us 20 years to put a serious dent in our filthy water trends, but we can begin to measure the impact in terms of years with sufficient resources and attention.

Please help me get the world out! I welcome your thoughts and suggestions.

Sincerely,

John Norwood

Polk County Soil and Water Commission

Join my Facebook Page John M. Norwood to keep up to date

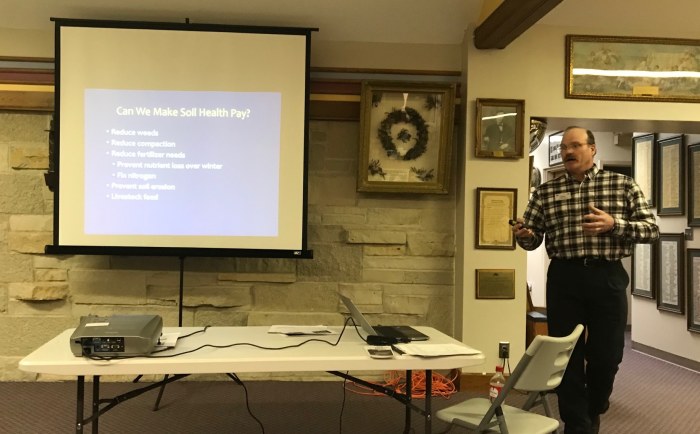

Top image: Photo by the author, taken at the February 27 meeting of Soil and Water Commissioners for Region 6, used with permission.

2 Comments

I have a lot of thoughts about this, and here are a few...

If we taxpayers are going to invest a whole lot more money in farm conservation, and I absolutely agree that we should, then we have the right to know where that funding is going, how it is being used, and what water quality results are being achieved. As of now, we don’t find out. As of now, landowner privacy laws mean that even Soil and Water Conservation Commissioners, who are supposed to be the local watchdogs of the system, are not allowed to know which specific land or landowners are getting farm conservation funds or which conservation practices are being implemented with those funds.

That makes it almost impossible to know what kinds of progress are being made in which local watersheds. The word ridiculous comes to mind. (And I say that as someone who is familiar with the system.)

And if we’re to have much more public investment in farm conservation, that investment needs to be matched with far more farmer/landowner accountability.

As of now, many if not most Iowa farmers and landowners are doing very little to protect water and seem to be hoping that other farmers and landowners will step up instead.

We need to establish benchmarks, standards, timelines, and deadlines, along with statewide systematic transparent water testing. Those are all measures that certain farm organizations successfully fought off when Iowa’s Nutrient Reduction Strategy was created. Meanwhile, input from Iowa conservation organizations was basically ignored. The result is a Strategy with good science and good information, but very little actual strategizing.

And yet ironically, the strategy part of the Strategy is working in the way it was intended to work. It was intended to provide political cover so Iowa elected officials and ag interests could claim that water concerns are being addressed, even though actual water progress is glacially slow. And when it comes to drainage pollution, the situation in some areas may be getting worse. During one rural drive this winter, I saw more acres with evidence of new pattern drainage tile than acres with cover crops. That is bad news for water quality.

As a taxpayer, I am very willing to pay a lot more for good farm conservation. But I also want the Iowa system to be changed. I’m tired of reading about the remarkable progress being made in the Chesapeake Bay, while Iowa waterways, at the rate we’re going, will be dirty forever.

The Chesapeake Bay strategy is successfully using the measures that the Iowa Strategy lacks. Farm conservation in the Bay watershed is no longer optional. Some farmers in the watershed are very unhappy about that. But the Bay is significantly healthier and cleaner, and it hasn’t taken fifty years.

If we want certain powerful Iowa farm organizations to remain as happy as possible, we should stick to what we’ve been doing. If we want clean water, it’s time for change.

PrairieFan Sat 2 Mar 1:24 AM

I just read that according to the newest Iowa Poll...

…only thirty percent of Iowans see water quality as a big problem. And that’s the single biggest reason Iowa’s surface water quality is so awful.

PrairieFan Sun 3 Mar 12:24 AM