Republican members of the U.S. House Intelligence Committee used most of their speaking time during recent impeachment hearings to run interference for President Donald Trump. They attacked the credibility of fact witnesses, pushed alternate narratives about foreign interference in U.S. politics, and tried to shift the focus to the whistleblower despite extensive corroborating evidence.

The Iowan who served on the House Judiciary Committee when Congress considered impeaching President Richard Nixon recalls GOP colleagues who were open to discovering and considering facts about the president’s possible high crimes and misdemeanors.

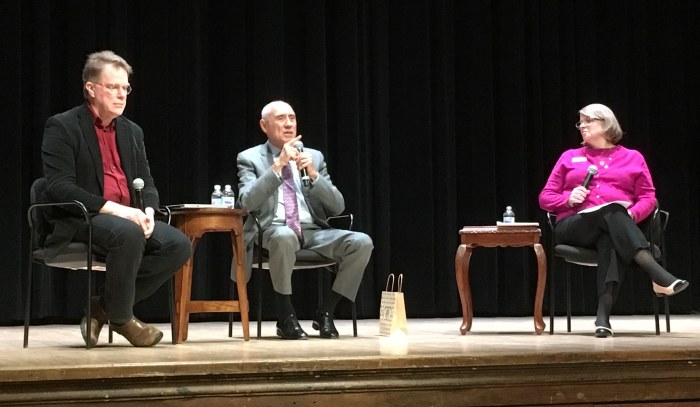

“The climate is so much different than what we went through during the period of Nixon,” former U.S. Representative Ed Mezvinsky told an audience at Iowa State University on November 14. Speaking at the ISU panel discussion on “Impeachment: Then and Now,” Mezvinsky recalled Republican colleagues who had “looked at impeachment in a very objective way.”

But the public hearings on Trump’s actions toward Ukraine demonstrated to Mezvinsky that “This is polarized. This is civil war. You watch those hearings and you wonder whether you’re in reality.”

Mezvinsky discussed that contrast further in a November 17 telephone interview with Bleeding Heartland.

“WE ALL SAT TOGETHER AND WE LISTENED TO TESTIMONY”

The House Judiciary Committee began holding hearings on impeaching Nixon in May 1974. Mezvinsky recalled that compared to this year’s investigations of Trump, “The process was different in that we all sat together and we listened to testimony.” As the committee learned more, certain Republican members “were obviously more receptive.”

One was a former FBI agent, Larry Hogan. He later became the only House Republican to vote for all three articles of impeachment that cleared the Judiciary committee.

Some Republicans regularly met with a few of the Judiciary Committee Democrats. One was Tom Railsback, who represented the part of Illinois just across the Mississippi River from Mezvinsky’s district covering southeast Iowa. Another was William Cohen, who later became a senator from Maine and served as defense secretary under President Bill Clinton. Several of them voted for one or more articles of impeachment.

PRESIDENTIAL PRESSURE, GERRYMANDERED DISTRICTS, AND MONEY IN POLITICS

There was broad consensus in Washington that Nixon’s involvement in the Watergate burglary and cover-up merited Congressional investigation. The House authorized a formal impeachment inquiry in February 1974 by 410 votes to 4, whereas zero House Republicans voted last month to launch an inquiry on impeaching Trump.

In 1974, many Republicans changed their views about impeachment as more evidence emerged. A turning point was the U.S. Supreme Court’s unanimous ruling in July that the White House had to release tapes of Nixon’s conversations.

Listening to those tapes affected “even the most recalcitrant Republicans,” Mezvinsky remembered. For instance, GOP Representative Charles Wiggins had consistently defended Nixon during months of Judiciary Committee hearings, saying no evidence directly linked the president to a crime. After hearing the “smoking gun” tape, Wiggins announced that “the facts then known to me have now changed,” adding that those facts “are legally sufficient in my opinion to sustain at least one count against the President of conspiracy to obstruct justice.”

In contrast, last week’s devastating testimony by Ambassador Gordon Sondland, former National Security Council official Fiona Hill, Lt. Colonel Alexandr Vindman, and others did not dent Republican opposition to impeaching Trump.

Does Mezvinsky have a theory on why today’s GOP members of Congress seem unmoved by facts about Trump’s conduct toward Ukraine? He cited three factors.

“One, they are pressured by Trump.” Having seen how the president deals with critics, they know he “will go after you” if you don’t support his position. “So the climate is different. I mean, Nixon–look, was no saint, but it wasn’t quite as overt.”

Second, Mezvinsky noted, “The districts are more gerrymandered and there are more hard-core Republicans” now. The GOP caucus in the 1970s included many moderates, who weren’t guaranteed to be re-elected in competitive districts. With fewer swing districts now, Republicans are more worried about a primary challenger than about winning the general election.

Money plays a different role in politics today, in Mezvinsky’s view. In the 1970s, money was mostly “below the table,” and there was less of it. More recently, especially since the Supreme Court’s Citizens United case, the money is “above the table.” Members of Congress know huge amounts may be spent against them in the next election.

“THE CHAIRMAN MADE IT A POINT THAT WE SHOULD WORK WITH THEM”

A current fault line in Democratic circles is whether the House should limit its impeachment inquiry to events related to squeezing Ukraine to boost Trump’s re-election chances, or whether Congress should consider other possible crimes like obstruction of justice or the violations of the emoluments clause. (That constitutional provision bans federal officeholders from receiving anything of value from a foreign state or its representatives.)

A similar divide existed in 1974, with some Democrats wanting to limit the articles of impeachment to matters related to the Watergate scandal. Mezvinsky was in the camp favoring a broader investigation. The Judiciary Committee voted on five articles of impeachment. Three passed with some bipartisan support. Two failed, rejected by some committee Democrats as well as Republicans. Mezvinsky was one of eight members who voted for all five articles.

In fact, Mezvinsky wrote article V, which charged that Nixon “knowingly and fraudulently” underpaid his federal income tax and benefited from government-financed improvements at two homes. The other article that didn’t pass out of committee accused Nixon of concealing American bombing operations in Cambodia from Congress.

Speaking to Bleeding Heartland last week, Mezvinsky remembered House Judiciary Committee Chair Peter Rodino “made it clear that for us to be effective–and he would tell us in our caucus, the Democratic caucus–we have to do it, whatever we have to do to make this bipartisan.” The Republican moderates “looked at the evidence in an open way, and the chairman made it a point that we should work with them.”

Within the caucus, they often discussed “how far to go” on impeachment. In fact, some Democratic colleagues discouraged Mezvinsky from presenting his article on tax evasion, “because the Republicans can’t support it.” There was a sense that “you’re going over the edge.”

He insisted on sponsoring the article anyway. They had compelling testimony from the former Internal Revenue Service commissioner, among others, and proof Nixon had backdated his deeds. “We had testimony from an assistant attorney general that said that if that was anybody else, that person would have gone to jail.”

Only twelve committee Democrats voted for impeachment Article V. In a piece later published in the Georgetown Law Journal, Mezvinsky and Doris Freedman wrote, “Most opponents of the tax article felt that willful tax evasion did not rise to the level of an impeachable offense requiring the removal of the president.”

“YOU MAY AS WELL ADD EVERYTHING THAT’S THERE AND PUT IT ON THE RECORD”

Should Democrats limit today’s impeachment inquiry? Mezvinsky commented that House Speaker Nancy Pelosi “was very hesitant to take up impeachment” until the Ukraine scandal broke. But he agrees with those in the caucus who thought presidential acts revealed in Special Counsel Robert Mueller’s report were “enough to bring an article of impeachment.” He feels the Judiciary Committee will have “a responsibility to look at other issues,” such as corruption or abuse described in the Mueller report, or false statements Trump may have submitted in written responses to Mueller.

The third charge the Judiciary Committee approved against Nixon (with two Republican votes) related to separation of powers and flouting the Congressional subpoena. The Trump administration has defied subpoenas in many matters, since long before the Ukraine inquiry. If Mezvinsky were serving now, he’d advocate for including that offense in any articles of impeachment.

Since House Republicans have made clear that none of them will vote to impeach Trump, would it be wise for House Democrats to limit their inquiry? Or would they do better to include anything potentially impeachable, from the emoluments violations to obstruction of Mueller’s investigation?

Mezvinsky speculated that some House Democrats won’t want a broader inquiry. That’s why Pelosi “was nervous” about going down this road. “That’s where impeachment is a political process,” he added. “It’s sort of a balance act.”

Thinking tactically, it occurred to me that if the Judiciary Committee prepares many charges, some Democrats from vulnerable districts that voted for Trump could stake out a moderate position. They might say to constituents, I thought some of the impeachment articles went too far, but I had to vote for these ones, because withholding military aid in order to pressure Ukraine to interfere in U.S. domestic politics is unacceptable.

Mezvinsky agreed; House members from redder districts can say some articles were too much for them.

“If Republicans stay the way they are, you may as well add everything that’s there and put it on the record,” he argued. Not only “for historical purposes,” but also as a matter of “judicial precedent, you may want to show it for the record.”

Democrats on Judiciary were trying to maintain the cooperation of GOP moderates in 1974. Now, that kind of Republican is “like an endangered species. They’re not around.”

POSTSCRIPT: GERALD FORD’S DEFINITION OF IMPEACHMENT

Mezvinsky recounted a memorable House Democratic caucus meeting in October 1973. That month in U.S. politics is best remembered for the “Saturday Night Massacre,” when the attorney general and deputy attorney general resigned in succession rather than carry out Nixon’s order to fire special prosecutor Archibald Cox, who was investigating the Watergate allegations.

Earlier that month, Vice President Spiro Agnew had resigned while facing criminal charges related to corruption as a county official and governor of Maryland. Under the 25th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, Nixon was to pick a new vice president, who would “take office upon confirmation by a majority vote of both Houses of Congress.”

Nixon had nominated House Minority Leader Gerald Ford. Few Democrats objected to the president’s choice. “We all liked Ford. He was a decent guy, a good member of the House, not like these Republicans now,” Mezvinsky said.

Nevertheless, he and some others argued that the Judiciary Committee should hold hearings on Ford’s nomination, in light of the 25th Amendment. While they were discussing the matter, Representative John Conyers, who also served on Judiciary, stated that Nixon would be impeached and removed from office. “I’ll never forget it,” Mezvinsky said. Although Watergate was in the news, Congress was months away from authorizing a formal impeachment inquiry. Conyers was one of the first House Democrats to see it coming. (It was later revealed that Conyers had a spot on Nixon’s “enemies list.”)

Mezvinsky voted to confirm Ford as vice president in December 1973, as did every other Iowan in the House at the time. The roll call was 387 to 35.

Near the end of our interview, Mezvinsky reminded me that Ford had famously provided a definition of impeachment. In a 1970 speech making the Republican case against Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas, the House Minority Leader declared, “an impeachable offense is whatever a majority of the House of Representatives considers it to be at a given moment in history.”

Top image: Ed Mezvinsky (center) speaks during a November 14 panel discussion on “Impeachment: Then and Now” at Iowa State University. On the left, ISU Professor Dirk Deam. On the right, moderator Karen Kedrowski, director of the university’s Carrie Chapman Catt Center for Women and Politics.

3 Comments

This reminds me...

…of the most recent edition of IOWA PRESS, wherein at some point, someone(s) said something about how a lot of Republican lawyers in Iowa aren’t “real Republicans” because they aren’t “Originalists.” Scary.

I’m old enough to have watched the Watergate hearings, and while what we learned then was disturbing and sometimes enraging, there was still a feeling, at least among the people I knew, that we were all one country and that our country would survive whatever happened. Ed Mezvinsky is right — that feeling is gone.

PrairieFan Sun 24 Nov 10:41 PM

Also Wiley Mayne

“Wiley Mayne was a four-term Republican United States Congressman from Iowa’s 6th congressional district. He was one of several Republican members of the House Judiciary Committee who were defeated in the fall of 1974 after he voted against resolutions to impeach President Richard M. Nixon in summer 1974.Wikipedia”

Berkeley. Bedell got his seat. A big improvement that hasn’t been equaled since in NW Iowa.

iowavoter Tue 26 Nov 7:58 AM

thanks for mentioning that!

Berkley Bedell was probably the best person who ever represented that part of Iowa in Congress.

Laura Belin Wed 27 Nov 12:45 AM