Governor Kim Reynolds announced more business closures on April 6, as the number of confirmed novel coronavirus (COVID-19) infections climbed to 946. Cases have nearly doubled the total of 497 on March 31. Confirmed deaths (now 25) have more than doubled from eleven on April 3.

Establishments now shuttered in Iowa include enclosed shopping malls (but not stores that can be accessed from outside the mall), arcades, outdoor and indoor playgrounds, social halls, bowling alleys, tobacco or vape stores, movie stores, and campgrounds.

Though Reynolds repeatedly urged Iowans to stay home if possible, and said the ban on gatherings larger than ten people will be enforced, she again stopped short of issuing a mandatory shelter-in-place order.

WHY IOWA REMAINS AN OUTLIER

When pressed on why Iowa is one of few states without such an order in place, Reynolds has fallen back on two talking points. First, she says, her decisions are informed by “data” and “metrics” provided by the Iowa Department of Public Health’s experts. Those metrics are fatally flawed, as the Iowa Fiscal Partnership’s Peter Fisher showed here. University of Iowa Professor Eli Perencevich, an epidemiologist, commented, “Instead of tracking the spread of disease to protect older Iowans, we are using them like a canary in the coal mine to determine how bad things are.” A forthcoming Bleeding Heartland post will further discuss the odd scoring criteria.

This piece will focus on the governor’s other refrain: her approach to slowing the spread of the virus is just like what’s happening in states with shelter-in-place orders. To hear Reynolds tell the story, critics fail to give her credit for prohibiting large gatherings and closing schools and certain businesses. During her April 3 news conference, she said,

This has become a divisive issue at a time when we must be united in our response to this crisis. I want Iowans to understand that we have taken significant and incremental steps to mitigate the spread of the virus [….]

We were ahead of many states in our response efforts, and we continue to dial up our mitigation efforts […].

Asked how she would respond to National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases Director Dr. Anthony Fauci, who had said the previous day he didn’t understand why all Americans weren’t subject to shelter-in-place orders, Reynolds replied, “I would say that maybe he doesn’t have all of the information” about what Iowa has been doing.

The talking points are contradictory, in that you can’t claim your “metrics” don’t indicate Iowa needs a shelter-in-place order, and simultaneously assert that what you’ve done is functionally the same thing.

Reynolds also glosses over the reality that many who have urged stronger action are well aware of her actions to date. They include numerous local government leaders, the top Democrats in the Iowa House and Senate, and health care professionals involved with the Iowa Medical Society and the Iowa Board of Medicine.

But for the sake of argument, let’s consider the governor’s point. Reynolds is correct that lots of businesses remain open in states where governors have ordered residents to stay at home. What would be different if she took the next step?

KEEPING MORE WORKERS SAFE

Since states have defined “essential” businesses differently, it’s hard to say how many companies would temporarily shut down parts of their operations if Reynolds ordered Iowans to stay at home. Many large employers fall into one of the U.S. Department of Homeland Security’s “essential critical infrastructure” categories, such as “food and agriculture.”

But some Iowa manufacturers or other facilities where employees work in close proximity to one another would face pressure to suspend their normal activity. Without a shelter-in-place order, employees who fear for their safety are at the mercy of their bosses. Aaron Calvin interviewed Wells Fargo call center workers about the problem in late March. It’s an ongoing issue for the bank nationally.

REDUCING EQUIPMENT SHORTAGES

Hospitals and clinics across the country lack sufficient personal protective equipment (PPE) to keep health care workers safe as they treat patients with severe COVID-19 infections. The Iowa Medical Society’s April 1 letter to Reynolds praised some aspects of the state’s response to the pandemic, but argued more steps are warranted. (emphasis in original)

This limited supply of PPE and other critical equipment has resulted in potentially dangerous efforts to reuse or otherwise conserve medical resources. Some practices report less than a two-day supply of PPE at current optimized use rates, and Iowa physicians live each day in fear that we are unnecessarily exposing ourselves and our families to illness as a result. […]

Iowa is now experiencing extensive community spread of COVID-19. We see the daily number of positive diagnoses growing exponentially and sadly, we see the number of Iowans in need of hospitalization or who have died as a result of the disease growing as well. Despite these concerning developments, we continue to witness individuals disregarding our collective calls for voluntary social distancing and several businesses continuing operations. Several industries, such as construction, are utilizing protective equipment that could be repurposed to fill the urgent need in healthcare, unnecessarily placing workers in close working conditions at a time when community spread of COVID-19 is on the rise, or risking workplace injuries that will further strain our emergency departments.

[…] Given the severe lack of PPE and ongoing issues with segments of our population not voluntarily social distancing, IMS believes the time has come to temporarily dial up our state’s response efforts. The physicians of Iowa request that you implement a more stringent shelter-in-place order for a period of at least two weeks.

We recognize that placing additional restrictions on industries will negatively impact Iowa’s economy and enforcing more stringent social distancing requirements will place an additional burden on first responders. We also know, based upon the experiences of other jurisdictions around the world, that these more stringent efforts will make a difference. By placing short-term, enforceable restrictions on greater segments of the economy, we can further slow the progression of the disease until resupply shipments of PPE and other critical medical equipment can arrive.

SENDING A CONSISTENT MESSAGE

For weeks, Reynolds and top public health officials urged Iowans to “stay home if you’re sick” and practice social distancing outside the home. Even now, the Iowa Department of Public Health’s webpage devoted to COVID-19 features a video State Medical Director Dr. Caitlin Pedati recorded on March 6, encouraging viewers to cover their cough, wash their hands, and stay home when they’re sick.

But asymptomatic people can carry and spread COVID-19. So a more effective mitigation strategy requires all of us to minimize our public outings. The governor took a step in the right direction on April 3 with a message on her official Twitter feed calling on Iowans to venture out for “Essential errands only”:

Here’s how you can help limit the spread of #COVIDー19! We all have a role to play. pic.twitter.com/BADxLg3OYz

— Gov. Kim Reynolds (@IAGovernor) April 3, 2020

Reynolds reinforced that message several times at her latest news conference. But she and others also referred to a ban on gatherings larger than ten people. Some people hearing that message will come away with the impression that it’s fine to socialize in smaller groups.

The Iowa Board of Medicine’s April 3 letter to Reynolds noted,

While your proclamations to date have certainly been critical and necessary steps in slowing the spread of COVID-19, we believe more can be done to “flatten the curve.” We have been made aware that the public may be confused about what it means to effectively practice social distancing, that Iowans are disregarding your recommendation to stay home, and that supplies of personal protective equipment (PPE) continue to dwindle.

Iowa House Minority Leader Todd Prichard and Senate Minority Leader Janet Petersen likewise argued in their letter to the governor on April 2, “A statewide shelter-in-place sends a clearer message about the serious nature of this pandemic. The current patchwork of recommendations is confusing, raising more questions than answers about what Iowans should be doing to help save lives.”

Iowa social media feeds are full of accounts of people regularly hanging out with friends in their homes or public places. A shelter-in-place order like those operating in harder-hit states would make clear that social visits with all others outside your household must stop. You can’t ask a few friends over for dinner or game night. You can’t arrange play dates or birthday parties for your child. And if you go out to exercise, you need to be alone or with other members of your household. No meeting up with friends or neighbors for a walk on the trail. California residents have been instructed to stay within five miles of their home when exercising outdoors.

HOW COULD SHELTER-IN-PLACE BE ENFORCED?

“I can’t lock the state down. I can’t lock everybody in their home,” Reynolds objected at her March 31 news conference. Indeed, she can’t. No one is claiming a shelter-in-place order would magically make all Iowans comply with social distancing recommendations.

Yet various services tracking cell phone data have found that residents of counties with stay-at-home orders have reduced their travel more than those living in other jurisdictions.

Iowa Department of Public Safety Commissioner Stephan Bayens said at the governor’s April 6 news conference that Reynolds would issue guidance this week to local law enforcement and police departments on their role in enforcing her various proclamations. “Law enforcement has no desire to cite or arrest anyone,” Bayens said. Officers would “seek first to educate the public on the law,” then “encourage Iowans to comply and disperse on their own,” and finally, “enforce the governor’s orders” as needed.

The same approach would apply to any additional restrictions Reynolds might impose on socializing in groups smaller than ten. I doubt police would issue many tickets. The order itself would persuade a larger number of Iowans to “own their behaviors and be part of the solution rather than the problem,” in Bayens’ words.

FINAL THOUGHTS

Reynolds often sounds defensive when reporters bring up this topic at news conferences. Instead of complaining that she’s not getting enough credit for what she’s already done, the governor should step back and consider why so many people don’t find those policies sufficient to meet the current challenge.

The Iowa Board of Medicine’s April 3 letter to Reynolds observed,

While issuing a shelter-in-place order and ensuring enforcement may seem drastic right now, it is imperative to do all we can to mitigate this disaster. In time, we may never know whether or not these drastic actions were the product of being overly cautious, but it will be abundantly clear if we failed to do enough. With that in mind, we urge you to take every reasonable action in your power to stop the spread of this disease immediately.

Everyone serving on that board was appointed by either Reynolds or her predecessor, Republican Governor Terry Branstad. They’re not out to make the governor look bad or score political points. Board member Dr. Warren Gall told the Des Moines Register on April 5, “We’re not trying to bully her or strongarm her” or “go over her head.” When the board voted to recommend a shelter-in-place order, they were trying “to tell the public that the medical profession is really quite concerned about the severity of this pandemic.”

For now, Reynolds appears determined to avoid a shelter-in-place order. On a conference call with Nebraska’s governor and Dr. Fauci shortly after the April 6 news conference, the governor defended Iowa’s current approach to social distancing. I hope her policies have the intended effect, but I’d feel more confident if she were following the advice of medical experts.

UPDATE: Fauci vouched for Reynolds at the White House press briefing on April 6.

Appreciate @POTUS for being a partner in our efforts to fight #COVID19. Very good conversation with Dr. Fauci today! @WhiteHouse pic.twitter.com/ibRIZccm6n

— Gov. Kim Reynolds (@IAGovernor) April 6, 2020

My transcript:

I had good conversations with the governor of Nebraska and the governor of Iowa here. And it’s interesting that functionally, even though they have not given a strict stay-at-home — what they are doing is really functionally equivalent to that. And we had a really good conversation with both of the governors.

You know, when I had mentioned that, I think there was a public response that they weren’t really doing anything at all and they really are doing a very good job. Both of them. Those are the only two that I spoke to. But it was a really good conversation. And I want to make sure people understand that just because they don’t have a very strict stay-at-home order, they have in place a lot of things that are totally compatible with what everyone else is doing.

My friends in several other states are under orders to minimize contact with anyone outside their household. Iowans are still getting a mixed message: on the one hand, stay home, but on the other hand, avoid gatherings larger than ten people. That will lead to much more casual socializing in small groups, which unfortunately facilitates community spread.

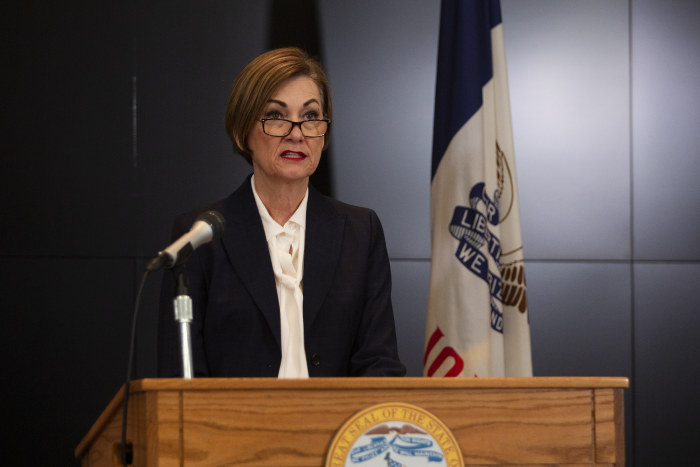

Top image: Governor Kim Reynolds speaks at her April 6 news conference. Photo by Olivia Sun/Des Moines Register (pool).

1 Comment

Thank you for this calm, measured, and very reasonable analysis

It makes much more sense than some of what has been said by the Reynolds administration.

And I hope the REGISTER will be successful in trying to obtain more information about the history and justification behind Reynolds’ twelve-point system via their public records request. Since Reynolds is choosing not to do what is being very justifiably asked by some members of the medical profession, the profession whose members have been risking their lives and their families’ lives in this pandemic, her office owes the Iowa public full information on why.

PrairieFan Mon 6 Apr 7:44 PM