John Aspray: “This pandemic was not the first sign of vulnerability in our food system. It just widened the cracks that have been there all along.” -promoted by Laura Belin

Every Iowan is familiar with the catchphrase “Iowa feeds the world.” But new data from the U.S. Department of Agriculture and Food & Water Watch shows the consolidation of corporate agriculture in the Hawkeye state is causing far more harm than good.

Every five years, the U.S. Department of Agriculture conducts a Census of Agriculture, asking every farm to provide detailed information on its operations. The 2017 Ag Census data was released last year, and tells a troubling story of consolidation in our agriculture system—a story that Iowa’s rural communities already know well.

The overall number of farms has decreased, as small and middle-sized farms are squeezed out by factory farms. Between 1997 and 2017, Iowa lost 85.5 percent (11,818) of its small- and medium-sized hog operations. As U.S. Secretary of Agriculture Sonny Perdue said, “In America, the big get bigger and the small go out.”

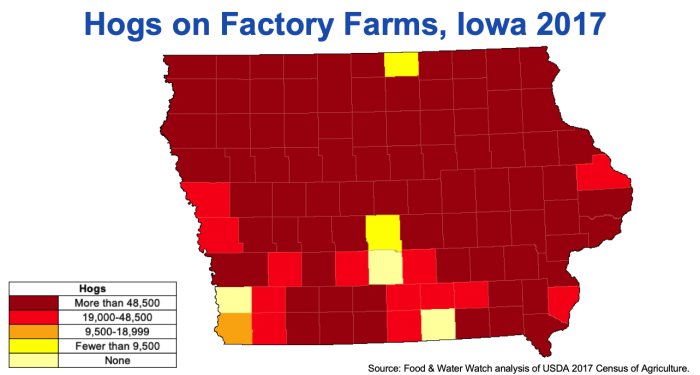

The “big” in Iowa have now grown so large that Iowa houses one-third of the nation’s factory farmed hogs. As of this 2017 data, that’s more than 22 million hogs or more than seven hogs per Iowan, on factory farms alone, and the total number of hogs has only grown since then. Iowa has been a hog farming state since the 1800s, but some very powerful companies have turned our food system into a bloated, unsafe, and profiteering business.

There are many reasons why this is a problem, but the first is simple: these hogs poop. A lot.

Each year, Iowa’s factory farmed hogs produce 72 billion pounds of manure—two and a half times the weight in human sewage produced by the entire New York City metropolitan area. But unlike big cities, which process and treat human waste, hog manure is rarely treated before it is released into the environment.

Instead, much of this hog manure is sprayed directly onto fields, often at rates that far exceed the soil’s ability to absorb it. The rest runs off into our waterways, resulting in nitrate and phosphate pollution, bacterial growth, and fish kills.

Iowa’s countryside might seem vast and sparsely populated, but big-city levels of waste are being produced on factory farms in many of Iowa’s most rural counties, with significant impacts on the people who live there. And the big meat companies refuse to pick up the bill for cleaning up their mess.

But it goes beyond factory farms themselves, and the hog manure produced. Along with corporate-owned factory farms come corporate-owned slaughterhouses. Over the past few decades slaughterhouses and processing facilities owned by corporations like Smithfield, Tyson, and JBS have taken over Iowa’s countryside.

These plants are notorious for their fast-paced, back-breaking and dangerous work of slaughtering and processing animal carcasses as quickly as possible. Before the current COVID-19 pandemic, the Trump administration moved to privatize inspection, placing the job of inspecting plants for food quality and worker safety in the hands of the same corporations that need to be inspected. With the fox guarding the henhouse, worker safety at these plants has taken a back seat to company profits.

Now, in the face of a pandemic, these corporations continued to prioritize their bottom line over adequately protecting workers, and because of that, meat processing facilities have become major coronavirus hotspots.

Instead of responding with hazard pay, appropriate PPE, and paid time off, the meat industry instead pushed the Trump administration to issue an executive order forcing the plants to stay open, even as elected officials in meatpacking towns expressed serious concerns. This behind-the-scenes lobbying was accompanied by a public campaign to stir up bogus fears of meat shortages. After all, to major corporations, what are thousands of workers’ lives worth, compared to their stock value?

It goes without saying that there have been serious economic consequences for the small and mid-sized farmers that have been forced to “go out.” But it’s more obvious than ever that the “get bigger” side of this equation has been just as, if not more, harmful.

This pandemic was not the first sign of vulnerability in our food system. It just widened the cracks that have been there all along. Iowans have been living for years with the environmental and community impacts of the factory farm takeover of our great state. It shouldn’t have taken a global pandemic for our society to take notice of the dangers of a consolidated food system. This new research makes it overwhelmingly clear: our “too big to fail” food system has failed all of us.

But now we have a choice. When the COVID-19 crisis is over, do we want a food system that values profits over people? Or do we have the political will and commitment to build a food system that works for all of us: farmers, plant workers, consumers, and the environment?

John Aspray is an Iowa organizer for Food & Water Watch and Food & Water Action, based in Des Moines.

1 Comment

Good piece that makes valid points

And not only do we need a better food system, we need a better agricultural system. The nutrient pollution from the conventional corn used to make ethanol is just as bad as the nutrient pollution from the conventional corn used to feed hogs.

PrairieFan Fri 15 May 3:21 PM