David Grussing: The Confederacy was not some romantic “Lost Cause” or a testament to the desire to pursue a differing form of government. -promoted by Laura Belin

In the past two or three months there have been stories from all viewpoints about removing Confederate monuments from public locations as well as removing the names of Confederate soldiers from various Department of Defense installations, streets, and vehicles.

As someone who served for 28 years as an Army and Army Reserve officer, I would like to offer my viewpoint on honoring members of the Confederate government or military.

As recently as this week, President Donald Trump has slammed NASCAR for their decision to ban Confederate flags at their events. I have been appalled at the number of Confederate apologists who seem to have come out of the woodwork, including people with absolutely no Southern heritage or background.

I’d like to think their defense was based on ignorance but, unfortunately, even after historical context has been provided to some of them they continue to voice the same tired arguments. Their default position seems to center around arguments like, “It’s about my heritage.” Or “Those monuments represent history.” Neither statement is true.

Monuments are not history. They serve to commemorate or memorialize an individual or event. They are not designed to teach history or provide any sort of analysis. They are there, not only as recognition of a particular person or event, but to serve as a testimony to the times in which they were erected.

It’s telling that none of the Confederate statues that are now a subject of debate were erected immediately after the Civil War nor were any of the Army installations named for Confederate figures named immediately after the war. The earliest Confederate statues began to be erected in the 1880s, but the majority were constructed in the early years of the 20th century. It is no coincidence that the years spanning the construction of these Confederate monuments coincides with the height of the Jim Crow era in the United States.

As far as heritage goes, it is a historical fact that all of the seven original Confederate states published Articles of Secession, which were accompanied by defenses attempting to explain why secession was both legal and necessary. Each of the original Confederate states listed their desire to protect, or even expand, the institution of slavery. So, in some respects, Confederate apologists are correct that the Civil War was about states’ rights. It’s just that the right that the Confederate states wanted to protect was the right to enslave African Americans.

Why are the Confederate generals and politicians memorialized in these statues not worthy of emulation? The answer is twofold. First, treason is one of three crimes, along with piracy and counterfeiting, specifically mentioned in the U.S. Constitution, and its elements are clearly spelled out. One of those elements is to take up arms against the government of the United States. By any reasonable definition of the word treason, these people were traitors whose actions resulted in the death of hundreds of thousands of United States soldiers, sailors, and Marines. It should be noted that more than 13,000 Iowans lost their lives fighting against the forces led by the officers and politicians commemorated by these Confederate statues.

The second reason the vast majority of Confederate officers are not worthy of respect is a bit personal for me but no less compelling. When I was commissioned as a new 2nd Lieutenant in the Army, I was required to swear the commissioning oath. The oath is as follows:

I solemnly swear to protect and defend the Constitution of the United States, against all enemies, foreign and domestic; that I will bear true faith and allegiance to the same; that I take this obligation freely, without any mental reservation or purpose of evasion; and that I will well and faithfully discharge the duties of the office on which I am about to enter, so help me God.

This oath is similar in content and nearly identical in purpose to the oath sworn by every one of the Confederate officers who had previously served in the U.S. Army or Navy. Since 1789, every officer who has entered the service of the United States has been required to take an oath, affirming their allegiance to the United States of America.

When the Confederate officers and politicians made the decision to take up arms against the country they had sworn to protect and defend, it was a conscious decision on their part to break their oath. Was it a given that because their state had left the Union that these officers had to take up arms against the Union? No, they had the option to resign their commission or to honor the oath they had taken.

A prominent example of a southern officer who refused to violate his oath was Major Robert Anderson. Major Anderson was a Kentuckian who, in 1861, was the commanding officer of the garrison at Fort Sumter, South Carolina. Not only did he remain true during his time at the commanding officer of Fort Sumter, he remained in the Union Army for the duration of the war and was given the honor of raising the U.S. flag at Fort Sumter when it was returned to Union control.

Although several Southern states used various arguments to justify secession, probably nothing more accurately captures the true motivation of the Confederate states than what became known as The Cornerstone Speech. This speech was given in March 1861 by Alexander Stephens, the Vice President of the Confederacy. The speech begins with Stephens expounding on the differences between the new Confederate Constitution and the United States Constitution.

After highlighting several differences in the two Constitutions, Stephens segues to the major thesis in his speech, that slavery is the rightful condition of blacks and that they are not equal to the white man. Stephens writes,

But not to be tedious in enumerating the numerous changes for the better, allow me to allude to one other though last, not least. The new constitution has put at rest, forever, all the agitating questions relating to our peculiar institution African slavery as it exists amongst us the proper status of the negro in our form of civilization. This was the immediate cause of the late rupture and present revolution. Jefferson in his forecast, had anticipated this, as the “rock upon which the old Union would split.” He was right. What was conjecture with him, is now a realized fact. But whether he fully comprehended the great truth upon which that rock stood and stands, may be doubted. The prevailing ideas entertained by him and most of the leading statesmen at the time of the formation of the old constitution, were that the enslavement of the African was in violation of the laws of nature; that it was wrong in principle, socially, morally, and politically. It was an evil they knew not well how to deal with, but the general opinion of the men of that day was that, somehow or other in the order of Providence, the institution would be evanescent and pass away. This idea, though not incorporated in the constitution, was the prevailing idea at that time. The constitution, it is true, secured every essential guarantee to the institution while it should last, and hence no argument can be justly urged against the constitutional guarantees thus secured, because of the common sentiment of the day. Those ideas, however, were fundamentally wrong. They rested upon the assumption of the equality of races. This was an error. It was a sandy foundation, and the government built upon it fell when the “storm came and the wind blew.”

Our new government is founded upon exactly the opposite idea; its foundations are laid, its corner-stone rests, upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery subordination to the superior race is his natural and normal condition. This, our new government, is the first, in the history of the world, based upon this great physical, philosophical, and moral truth. This truth has been slow in the process of its development, like all other truths in the various departments of science. It has been so even amongst us. Many who hear me, perhaps, can recollect well, that this truth was not generally admitted, even within their day. The errors of the past generation still clung to many as late as twenty years ago. Those at the North, who still cling to these errors, with a zeal above knowledge, we justly denominate fanatics.

Every time I read the words of Alexander Stephens, two things stand out to me. First, his reasons for the establishment of the Confederacy are so clear and concise that there is no possibility of misunderstanding his message. “Our new government exists […] its cornerstone rests upon the great truth that the negro is not equal to the white man; that slavery subordination to the superior race is his natural and normal condition.” Those words should dispel, for any thinking person, the notion that the Civil War was about anything other than the desire to perpetuate the institution of slavery.

The second thing that stands out to me is the willful ignorance of many modern supporters of the Confederacy. Nearly everyone in this country has access to a computer and with that access, the Cornerstone Speech, as well as all the state defenses of secession, is readily available. If a supporter of the Confederacy looks up any of this information and still expresses their support for the principles on which the Confederacy was founded, they are racists, pure and simple.

It isn’t just the preservation of Confederate symbols and monuments that Donald Trump supports. He has also expressed his vehement opposition to renaming Army installations that were named after Confederate generals. Indeed, he has even threatened to veto the National Defense Authorization Act–which provides, among other things, for pay raises for our troops–if it includes any provision for renaming any military bases.

There are ten Army installations named for Confederate generals. All were named either during the early years of the 20th century or at the beginning of World War II. All are located in former Confederate states: Fort Bragg, NC, Fort A.P Hill, VA, Fort Benning, GA, Fort Hood, TX, Fort Lee, VA, Fort Rucker, AL, Fort Polk, LA, Fort Pickett, VA, Camp Beauregard, LA, and Fort Gordon, GA.

Rather than addressing the namesakes of each of these ten installations, I will highlight two major Army installations: Fort Bragg and Fort Hood.

Fort Bragg is home to the XVIII Airborne Corps and the Army Special Operations Command. It was named after Braxton Bragg in 1918. Bragg was a West Point graduate who served in both the second Seminole War and the Mexican-American War. He resigned from the Army in 1856 to become a sugar plantation owner in Louisiana where he utilized 105 slaves on his plantation. When the Civil War began, he accepted a commission in the Confederate Army.

Bragg was fairly successful as a trainer of troops, but when put into field commands he is generally considered as one of the worst general officers on either side of the conflict. He had a reputation for unimaginative tactics and a personality that offended peers, superiors, and subordinates alike.

One such story, told by Ulysses Grant, describes Bragg as a company commander at a frontier fort where he was also assigned the additional duty of post quartermaster. As a company commander, Bragg submitted a requisition for supplies but then, in his capacity as quartermaster, turned down the request. Company commander Bragg resubmitted the request with more justification only to have it rejected again by quartermaster Bragg. Company commander Bragg then complained to the post commander who reportedly responded, “By God, Bragg, you have argued with every officer in the Army but now you are arguing with yourself!”

Fort Hood is the largest Army installation in terms of population in the United States and is the Headquarters of III Corps, First Army Division West, the 1st Cavalry Division, and the 3rd Cavalry Regiment. It was named after John Bell Hood when the post opened in 1942. Hood had graduated from West Point and had served as a US Army officer with assignments in Texas and California until he resigned his commission and offered his services to the state of Texas, even though he was not a Texan. He was a fairly successful brigade and division commander, but when he was assigned as an Army commander, he was not effective.

His views on race alone should be ample reason to rename Fort Hood. In a letter he wrote to William Sherman on September 12, 1864,

You came into our country with your Army, avowedly for the purpose of subjugating free white men, women, and children, and not only intend to rule over them but you make negroes your allies, and desire to place over us an inferior race, which we have raised from barbarism to its present position, which is the highest ever attained by that race, in any country in all time.

The actions and comments of Braxton Bragg and John Bell Hood are typical of the other Confederate officers who were honored by having Army installations named after them. The Army and the Department of Defense have accepted the need to at least discuss the possibility of renaming these installations. Members of Congress, from both political parties, are now on board and recognize the necessity of renaming these installations for American heroes who actually deserve recognition. The main opponent to this much needed change is Trump, a man with no Southern heritage as well as someone who never served a day in the military.

The words of Confederate leaders themselves clearly spell out the basis for the Confederate state. It was not some romantic “Lost Cause” or a testament to the desire to pursue a differing form of government. The states of the Confederacy left the Union for one reason and one reason only. That reason was to perpetuate, and hopefully expand, the ability to enslave African-Americans.

Supporters of Confederate figures and monuments need to be recognized as what they are: either individuals who are ignorant of the well-documented history concerning the formation of the Confederate States, or racists. There is no middle ground.

David Grussing is a veteran of the U.S. Army and Army Reserve and a retired police officer living in Emmet County.

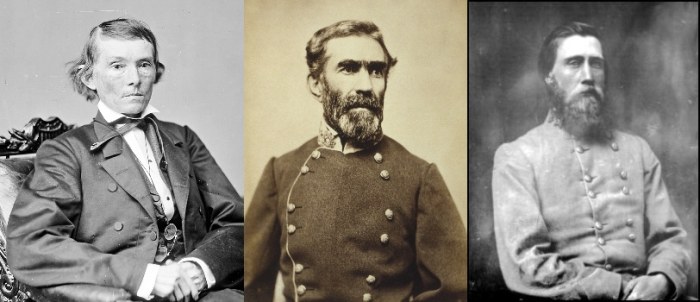

Top image: From left, Alexander Hamilton Stephens, Braxton Bragg, and John Bell Hood.

2 Comments

Big Thanks...

…To Mr. Gussing and to Ms. Belin for this ‘history revisited.” As an African American, I and my family know these things well, but denial runs deep here in my home state. Just because Steve King, the poster child for Iowa’s racists, is being put down doesn’t mean Iowa’s problem is going away. Again thanks for your honesty and courage. Moral warriors are hard to find these days.

dbmarin Fri 10 Jul 8:32 AM

I never saw the Cornerstone Speech until I was an adult...

…and I should have learned about it in high school. Thank you to all Iowa teachers who provide their students with a better history education than I received, in spite of all the difficulties of doing so.

PrairieFan Fri 10 Jul 11:18 AM