Dan Piller: The “Farmers Holiday” movement was the Black Lives Matter of the Corn Belt during the early 1930s. Mass protests, including blocking traffic, changed government policy.-promoted by Laura Belin

The churches, coffee shops, and co-operatives of northwest Iowa that gave us Steve King and a huge majority for Donald Trump in 2016 are no doubt generating massive disapproval of the Black Lives Matter protests, adding their voices to the call for “law and order” in the distant cities.

It might come as a surprise to many of these folks, who probably nodded through their Iowa history courses, that they enjoy their status as entitled owners of some of the richest farm land in the world primarily due to the government rescue of agriculture in 1933. That policy was a response to civil disorders that on several occasions prompted the governors of Iowa and Nebraska to call out their National Guards.

The Black Lives Matter equivalent in those days was something called the Farmers Holiday. Nine decades ago, angry at a decade of low commodity prices, scant profits and steady stream of foreclosures that forced their neighbors off their land, the farmers weren’t shy about blocking roads to prevent price-destroying surplus grain and milk from reaching markets. They even threatened a judge with a hangman’s noose.

And it was in western Iowa where the Farmers Holiday reached its denouement.

During the dark Great Depression winter of 1932-1933, president-elect Franklin D. Roosevelt was heard to muse that if a Soviet-style takeover occurred in the U.S., it would happen not in the big cities that since the Wall Street crash of 1929 had been surprisingly peaceful, but in the Midwest where farmers were becoming increasingly belligerent and violent. FDR’s concerns about American agrarian Bolshevism were well-founded; communists openly used Sioux City and Omaha as their bases for forays into Iowa and Nebraska corn fields.

For the fall of 1933, the Farmers Holiday promised an action that struck panicked fear in the hearts of members of Congress, governors and the incoming Roosevelt administration. Black Lives Matter can, at best, generate protests and a smattering of violence in one sector of a big city. The dream of the Farmers Holiday was far more aggressive: to induce slow starvation in the cities as grocery shelves emptied, not to be restocked.

The newly-inaugurated powers in Washington, D.C., were not of a mind to wait to see if the Farmers Holiday could knit together hundreds of thousands of individualistic farmers in a coherent economic action. In May 1933, as part of FDR’s famous “Hundred Days” that launched the New Deal, Roosevelt and Secretary of Agriculture Henry A. Wallace (an Iowan) persuaded a reluctant Congress to pass the Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1933.

For the first time in history, that act paid farmers to not plant fields and to store their grain rather than take it to market. The goal was to work off the surpluses that had driven corn prices to as low as 20 cents per bushel and hog prices to 5 cents per pound.

Desperate farmers had already shelved their congenital Republicanism to give their majority to Roosevelt over Iowa-born Herbert Hoover in the 1932 presidential election. Now they swallowed their longtime scruple against government assistance and signed up for Wallace’s “Ever Normal Granary,” which involved inspections of their corn cribs after harvest to make sure they weren’t cheating by taking grain to market on the sly.

Those farm subsidies continue to this day. Among the recipients are many honored “Century Farms” that most likely would have been lost in the economic cataclysm of the Great Depression without federal government aid. Their owners now form the core of the majorities given to right-wing politicians like King and Trump.

Black Lives Matter awaits a similar redemption of its mission.

EARLY U.S. GOVERNMENT INVOLVEMENT IN AGRICULTURE

At the beginning of the Republic in 1789, the new United States was a primarily agricultural nation, with 90 percent of its citizens living on farms. George Washington and Thomas Jefferson considered themselves less founding fathers than active, working farmers. Agriculture, like most American enterprises, existed without government aid or interference. Farmers’ only concerns were periodic efforts by New England industrialists to impose tariffs, which inevitably rebounded to the export disadvantage of farmers whose increasing productivity on newly-opened lands west of the Appalachian Mountains caused surpluses of corn, wheat and cotton to pile up.

Despite repeated defeats on the early Civil War battlefields, Congress and President Abraham Lincoln had enough faith in the Union cause in 1862 to begin involving the federal government in agriculture. First, Congress established the Department of Agriculture primarily to prepare for the inclusion of new lands west of the Missouri River that were to be given over primarily to cultivation. Congress also passed the Pacific Railroad Act, which set construction of the Union Pacific Railroad from Omaha to the California coast, and also set aside lands for Land Grant universities. The latter act would revolutionize higher education in the U.S. (and provide a key growth area for college sports a century later).

But the crown jewel of this new government activism in agriculture was the Homestead Act, which promised 160 acres of free land in new territories west of the Missouri River to any prospective farmer who worked the land for five years. The Homestead Act was intended primarily to be the traditional land reward for Union Army veterans, and not, sadly, for the soon-to-be emancipated African Americans–who would still be confined in servitude to what was left of southern cotton plantations.

After Appomattox the U.S. busied itself with finishing the Pacific railroad, clearing uncooperative Native Americans from lands once promised to them so that Homesteaders could come in to farm, and nursing along the network of Land Grant agricultural and engineering colleges. When not enough native-born Americans wanted to hazard life on the forbidding prairies west of the Missouri River, railroad land agents combed Russia, Eastern Europe and Scandinavia for hardy, optimistic folks willing to endure one hundred degree weather extremes, grasshoppers, and uncertain rainfall to make crops on land that had never been broken.

By the 1890s the results were mixed. The U.S was now a world agricultural power and western states had emerged as agrarian bastions. But the small Homestead farmers were too numerous and fragmented to have any kind of pricing power for their grain and livestock. They were at the mercy of the railroads, banks and grain buyers.

Years of financial uncertainty exploded into the Populist movement, which reached its apogee in 1896 with the nomination of Nebraskan William Jennings Bryan as Democratic candidate for the presidency. Bryan lost the first of his three tries for the White House, but he lived to see many of his ideas such as the income tax, the Federal Reserve central bank and the partial breakup of big railroad and banking trusts come to fruition.

MASS PROTESTS CHANGE GOVERNMENT APPROACH

But for all the Populist wind coming from the prairies, Washington declined to give farmers any kind of direct financial aid. That policy was reinforced during the Republican administrations of Warren Harding, Calvin Coolidge, and Herbert Hoover in the 1920s, a decade where World War I-induced high commodity prices were quickly short-circuited by trade-killing tariffs that returned farmers to their old dilemma of grain and livestock prices that fell below the costs of production. Farm bankruptcies and foreclosures mounted.

The problem worsened after the Wall Street crash of 1929. The economic depression farmers had experienced for almost a decade was now visited on the cities, with resultant price-killing drop in demand for higher-value beef, pork and chicken.

In the early 1930s, two Iowans played crucial roles as agriculture thrashed desperately for a way out of its economic bind. One was Henry A. Wallace, an odd combination of the plant scientist who would be one of the inventors of hybrid corn and also editor of his influential family publication, Wallace’s Farmer.

While he struggled to get his Pioneer Hi-Bred company off the ground selling hybrid corn to skeptical farmers (aided by a garrulous farmer-turned-real estate salesman named Roswell Garst), Wallace used his editor’s position to advocate more direct government aid to farmers.

By late 1932, Wallace’s stature was sufficient to earn a place in the new cabinet of the incoming Roosevelt administration, despite the fact that Wallace had never participated in partisan politics. That omission, no doubt, sat well with Democrat FDR, since Wallace was a registered Republican.

While Wallace offered the cool intellectualism of a scientist to farm debate, Wapello County native Milo Reno brought rhetorical heat. A onetime insurance company executive, Reno drifted into farm organization politics in the 1920s and by 1930 hatched the idea of a nationwide farm strike, or Farmers Holiday.

The challenge of organizing the one-quarter of the 123 million Americans who lived on farms in those days (Iowa had 275,000 farm operations in 1930, almost quadruple the state’s total today) seemed insurmountable, but the fiery Reno attracted attention and political tension by organizing marches and filling arenas in farm belt cities with angry farmers, singing their chant to city people “it’s a holiday we’ll hold. We’ll eat our ham and eggs and you can eat your gold.”

The Farmers Holiday movement attracted some colorful hangers-on, none more distinctive than Ella Reeve “Mother” Bloor, a grandmotherly-appearing figure who was in her 60s by the 1930s but held a resume that included service with Eugene Debs in the American Socialist Party and later, the U.S. Communist Party.

Mother Bloor operated openly from Sioux City and proved adroit at evading various attempts at prosecution while becoming a familiar figure at Farmers Holiday meetings. Her Midwestern career would reach its peak in 1934 when she helped touch off a riot at a meatpacking plant at the central Nebraska town of Loup City.

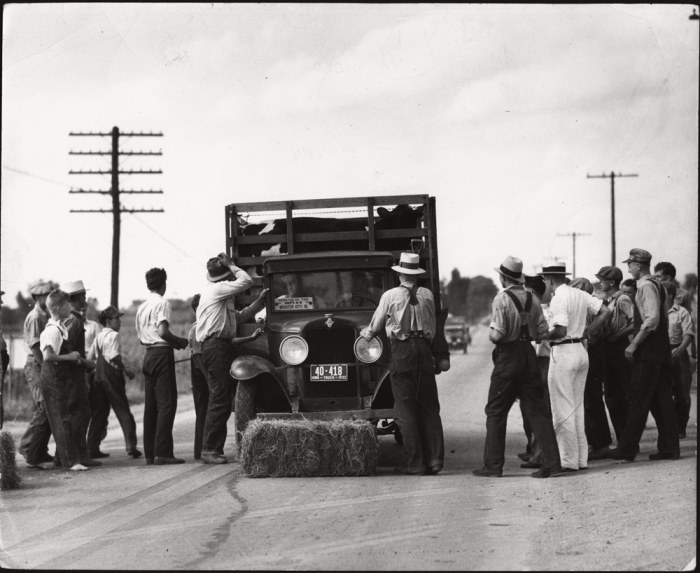

As the 1932 harvest season approached, the Farmers Holiday appeared to reach a critical mass, particularly in western Iowa. Roads in and out of elevators and livestock markets in Council Bluffs, Sioux City and scores of other smaller western Iowa towns were blocked by telephone poles felled by farmers. Trucks carrying milk were seized and their contents dumped on the ground. The Farmers Holiday, which now had chapters in 88 of Iowa’s 99 counties, claimed credit for those actions. Dozens of farmers spent brief time in county jails.

On several occasions, foreclosure auctions turned violent. The Iowa National Guard had to be called to Denison to break up a mob that had gathered at a foreclosed farm. Farmers also used another tactic, the so-called Penny Auctions,” where farmers offered only pennies to the foreclosure auctioneer, their menacing stares precluding legitimate bids.

In early 1933 Reno’s Farmers Holiday filled the Iowa and Nebraska state capitols, a show of force strong enough to produce two-year moratoriums on foreclosures. But insurance companies who had been major lenders to agriculture in the heyday of high prices during and immediately after World War I, challenged the moratorium by continuing to file for foreclosure proceedings. At one such session at the Plymouth County Courthouse in LeMars, a hapless judge was dragged from his bench, taken out of town to face a hangman’s noose from a tree. The farmers let the jurist go after splattering him with mud, but the account of the incident made Page One of the New York Times.

As farmers began to plant in the spring of 1933, just weeks after the new Roosevelt administration and Democratic-majority Congress had taken power, Reno called a nationwide Farmers Holiday for the coming fall harvest season. If Reno had his way, America’s town and city dwellers would face food shortages by the coming winter.

That was enough for Roosevelt and Wallace. After FDR dealt with the bank crisis emergency that overshadowed his own inauguration in March, the newly-installed “brain trust” at the White House and USDA crafted the nation’s first-ever government program to pay farmers to withhold a portion of their grain harvest and to eliminate (usually by shooting) surplus hogs. The Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1933 was passed in the nick of time, and the subsequent federal dollars that flowed to farmers knocked the legs out from Milo Reno and the Farmers Holiday.

All was not happy; the USDA, having nowhere near the personnel to ensure that farmers were keeping their grain bins locked after the 1933 corn harvest, had to rely on farmer committees to do the inspections. The notion of farmers snooping on one another spoiled numerous family relationships and friendships, but by 1934 farm foreclosures were down and farmers finally had money in their pockets to pay their property taxes and make themselves whole on their mortgages.

That year, and again in 1936, killing heat waves and droughts (most Iowa temperature heat records were set in those years), virtually wiped out Midwestern corn crops but the tightened supplies perversely raised the price of corn back to $1 per bushel and more. Farmers could afford the more expensive, but higher-yielding hybrid corn and they also could invest in the new mechanized tractor technology that by the onset of World War II had ended the old practice of planting and harvesting by hand.

After V-J Day, farmers enthusiastically planted fence row-to fence row to feed war-devastated Europe, and Washington was only too willing to continue the New Deal subsidies to farmers regardless of which party was in power.

But nine decades after the federal government began making direct payments to farmers, few remember that those subsidies–which ensured peace on the prairies through the Farm Crisis of the 1980s and the turmoil caused by Donald Trump’s trade wars–began with the fear and violence of the Farmers Holiday.

Dan Piller was a business reporter for more than four decades, working for the Des Moines Register and the Fort Worth Star-Telegram. He covered the oil and gas industry while in Texas and was the Register’s agriculture reporter before his retirement in 2013. He lives in Urbandale.

Top image: Farmers Strike in Sioux City, 1932, courtesy of the State Historical Society of Iowa.

Editor’s note: This 1935 report by the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Bureau of Agricultural Economics chronicles farmers’ and farm laborers’ strikes and riots from 1932 to 1935.

1 Comment

This is a really interesting history, thank you!

And speaking of farm subsidies, I’ve seen little media coverage of the fact that much of the derecho crop damage will be covered by crop insurance which is heavily subsidized by taxpayers. And our governor recently decided that a hundred million dollars of federal covid funding will also go to Iowa agriculture. (David Osterberg wrote a good op-ed piece in the CEDAR RAPIDS GAZETTE, pointing out that many urban homeowners and renters suffered damage that isn’t getting as much political attention as the farm damage.)

Anyone interested in how Native Americans lost land so that Iowa farmers could gain land can also read the history of the Missouri River and where and why the reservoirs were built.

PrairieFan Sat 29 Aug 8:06 PM