Herb Strentz recalls the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, comprised of second-generation Nisei (Japanese-Americans) who fought for the U.S. during World War II. -promoted by Laura Belin

Not often is something timely when it is 70 to 75 years overdue.

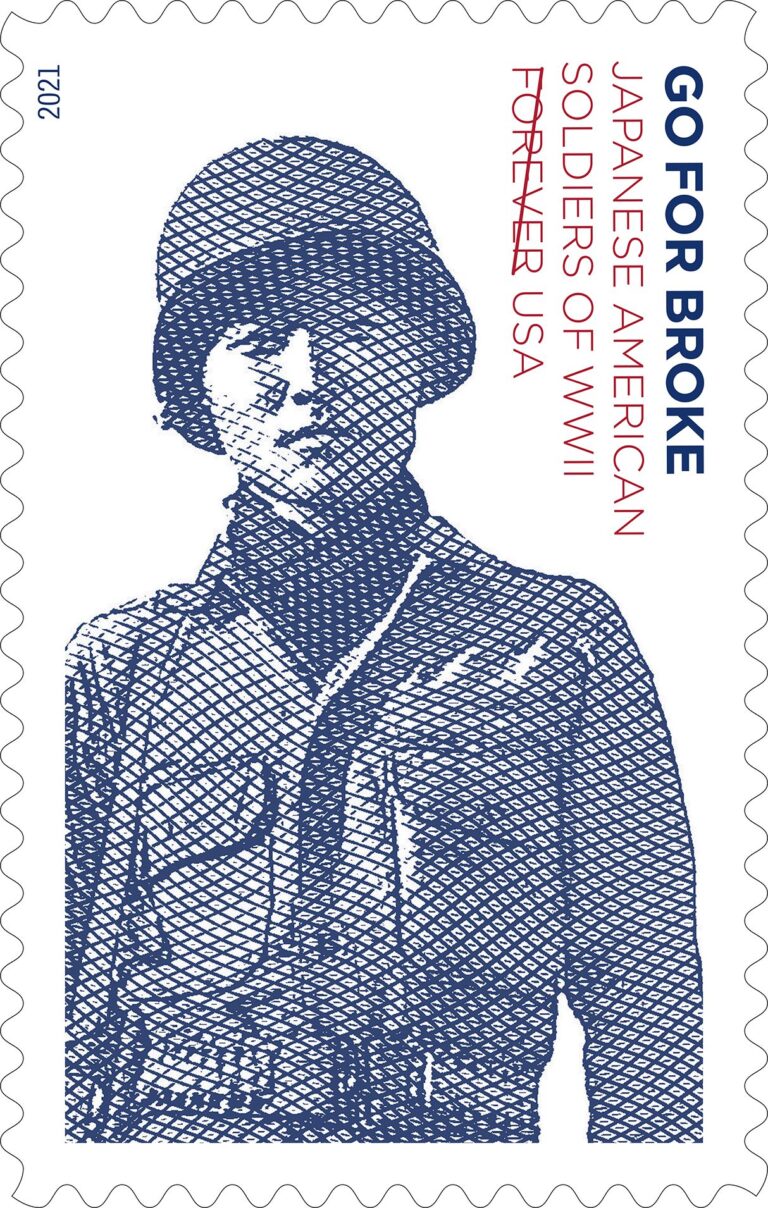

But that is the case with an upcoming 2021 commemorative stamp, a tribute to World War II patriotism.

The nation finally is giving such recognition to some 33,000 Japanese-Americans who served in U.S. armed forces in World War II. At the heart of this recognition are the combined 100th Infantry Battalion and 442nd Regimental Combat Team, comprised of second-generation Nisei, American citizens by birth. The 442nd became the most decorated American military unit ever for its size and length of service.

The 442nd’s 18,000 decorations include 9,500 Purple Hearts, 5,200 Bronze Stars, 588 Silver Stars, and 21 awards of the Congressional Medal of Honor. The unit had its roots in the Hawaii Army National Guard, where its motto was “Go for Broke,” akin to phrases in gambling like “shoot the work” or “all in,” recognizing the risks being taken.

Depending on whether you use the unit’s assigned number — accounts say 3,000 to 4,000 — or all the soldiers who served in the 442nd, perhaps 14,000, the percentage of those serving in the 442nd who were killed or wounded is reported at more than 90 percent.

So some 75 years after World War II and after at least 15 years of lobbying, the heroism and patriotism of the Japanese-Americans is recognized at the same time we experience revival of the notion of “white supremacy” in the U.S.

When he authorized creation of the 442nd in 1943, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt declared that “Americanism is a matter of the mind and heart; Americanism is not, and never was a matter of race or ancestry.”

That damning of racism, however, came about a year after FDR had issued Executive Order 9066, which mandated the incarceration of some 112,000 Japanese Americans into ten camps, mostly in the western U.S.

Those incarcerations may have contributed to opposition to creating a Nisei combat unit, and the incarcerations continued through war’s end even as soldiers from those families were serving in the 442nd.

As President Harry S Truman told members of the 442nd at the White House in July 1946, the year the 442nd was deactivated, “You fought the enemy abroad and prejudice at home and you won.”

Truman later issued Executive Order 9981 in 1948, mandating desegregation of the Armed Forces.

The commemorative 55-cent “Forever” stamp, to be issued later this year, is in tribute to those victories against Hitler in Europe and prejudice both in Europe and at home.

And yet the thousands of commemorative stamps already issued might raise questions about why it took so long for the “Go for Broke” commemorative. After all, cartoon characters like Daffy Duck, Dick Tracy, and Garfield the cat have had their commemoratives, as have leaders of the Confederacy and other curious choices, like the Alcatraz penitentiary.

The most painful and the most frequently told account of the prejudice and patriotism in the 442nd story is their rescue of a “lost battalion” in warfare in France. Soldiers from a former Texas National Guard unit, now part of the 36th Infantry Division, were trapped by German soldiers, and efforts to save them had failed. General John Dahlquist in late October 1944 ordered an already battle-weary 442nd to save them. Which they did on October 30. 211 Texans were saved by the 442nd at a cost of 800 Nisei casualties, including 200 killed.

The remnants of the 442nd were then ordered into yet another battle.

To cap that, at a November 12, 1944 parade review he had ordered, Dahlquist was upset by what he considered to be low turnout among the troops, taking it as a personal affront. He reprimanded a lieutenant colonel for the failure of the Nisei to show up. He was informed, “General, this is the regiment. The rest are either dead or in the hospital.”

Nonetheless, the war records of the 442nd gave spirit, pride and hope to their families and other Japanese-Americans still in the 10 incarceration camps back home. The 442nd put an exclamation point on FDR’s statement, “Americanism is not, and never was a matter of race or ancestry” — although it also accentuated the difference between the 1943 statement and the racism inherent in Executive Order 9066.

In the camp in Minidoka, Idaho, were the maternal grandparents of Neil Nakadate of Ames, Iowa, now an emeritus professor of English at Iowa State. He tells the stories of his mother’s family — who were taken from their home in Portland, Oregon — and his extended family in Looking after Minidoka: An American Memoir, published by the Indiana University Press. His father, Katsumi (James) Nakadate, was a physician and lieutenant in the medical corps and attached to the 442nd until being reassigned to the 17th Airborne.

Some closing thoughts:

Top image: National Archives photo of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, somewhere in France in 1944.

Herb Strentz was dean of the Drake School of Journalism from 1975 to 1988 and professor there until retirement in 2004. He was executive secretary of the Iowa Freedom of Information Council from its founding in 1976 to 2000.

1 Comment

Great story, thank you!

I first read about part of this story in the Michener novel HAWAII. And then I met a Japanese-American college student in my dorm who told me a little about her family members who were interned. I wish I had asked many more questions and listened harder. We grow too soon old and too late smart.

PrairieFan Fri 8 Jan 9:37 PM