The latest Iowa employment statistics “are disappointing,” Iowa State University economist Dave Swenson tweeted on September 17 after the U.S. Department of Labor released new figures for August. Swenson noted, “Total employed and total labor force are down, unemployment levels rose slightly, and unemployment rate is unchanged” at 4.1 percent. Meanwhile, payroll nonfarm jobs declined.

Governor Kim Reynolds’ decision to cut off pandemic-related federal unemployment benefits in June (three months early) “to goose the economy turned out to be a dud,” in Swenson’s view.

A growing body of research supports that conclusion.

Ever since a group of Republican-controlled states stopped participating in pandemic-related unemployment programs, researchers have been trying to gauge the impact. They’ve tracked online job searches and found clicks on job posting briefly increased, then dropped below the April baseline. They’ve examined census survey data and found that in twelve states that cut the benefits in mid-June, there was “no uptick in employment,” but a measurable increase in respondents having trouble paying for usual household expenses.

A Wall Street Journal analysis indicated that payrolls increased by 1.33 percent from April through July in states that cut unemployment benefits early, but increased by 1.37 percent in states that continued to participate.

Ben Casselman reported for the New York Times on the latest signs that the policy “had little effect on employment but sharply cut spending, potentially hurting state economies.” U.S. Department of Labor figures released on September 17 “showed that the states that cut benefits have experienced job growth similar to — and perhaps slightly slower than — growth in states that retained the benefits. That was true even in the leisure and hospitality sector, where businesses have been particularly vocal in their complaints about the benefits.”

Data compiled by Swenson indicates that Iowa’s leisure and hospitality sector employed about 10 percent fewer people in August 2021 than in February 2020. Only the information sector is still so far below pre-pandemic employment levels. Restaurant owners were among the loudest voices in the business community cheering Reynolds’ decision to reduce income for jobless Iowans. But taking more than $30 million per week in federal funds out of the state’s economy didn’t solve workforce shortages for retail businesses or restaurants.

Casselman’s New York Times article also highlighted a recent study incorporating data from nineteen states, including Iowa. The economists reviewed “anonymized banking records from more than 18,000 low-income workers who were receiving unemployment benefits in late April.”

They found that ending the benefits did have an effect on employment: In states that cut off benefits, about 26 percent of people in the study were working in early August, compared with about 22 percent of people in states that continued the benefits.

But far more people did not find jobs. The researchers had data for 19 states that ended the programs; in those places, they found that about 1.1 million people lost benefits because of the cutoff, and that only about 145,000 of them found jobs. (The researchers argue that the true number is probably even lower, because the workers they were studying were the people most likely to be severely affected by the loss of income, and therefore may not have been representative of everyone receiving benefits.) […]

Cutting off the benefits left unemployed workers worse off on average. The researchers estimate that workers lost an average of $278 a week in benefits because of the change, and gained just $14 a week in earnings. They compensated by cutting spending by $145 a week — a roughly 20 percent reduction — and thus put less money into their local economies

When announcing her decision in May, Reynolds claimed the extra benefits were “discouraging people from returning to work.” But University of Toronto economist Michael Stepner, an author of the new study, told Casselman, “The labor market didn’t pop after you kicked these people off […] Most of these people are not finding jobs, and it’s going to take them a long time to get their earnings back.”

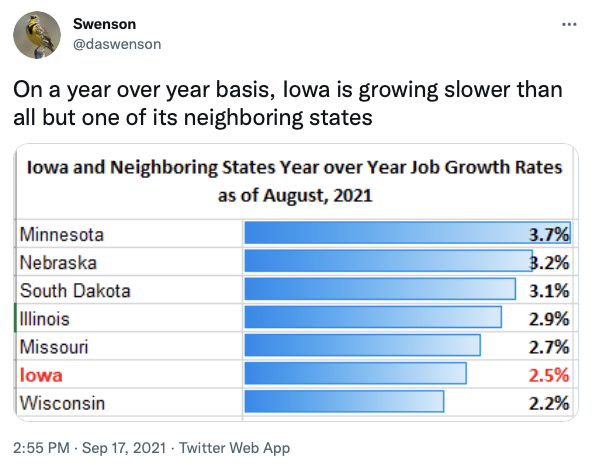

While Reynolds frequently touts Iowa’s supposedly strong comeback from the pandemic, the reality is that our recovery lags that of most neighboring states.

On a year over year basis, Iowa is growing slower than all but one of its neighboring states pic.twitter.com/B8tSC6Q9C1

— Swenson (@daswenson) September 17, 2021

Swenson tweeted on September 17 that states continuing to participate in the pandemic-related unemployment programs had job growth of 0.17 percent in August, above the national average of 0.09 percent. Meanwhile, the group of states that ended federal unemployment insurance early had on average no job growth last month. Swenson told the Des Moines Register’s Tyler Jett that the benefit cuts “backfired,” causing a “decline in consumption” that “in and of itself was probably a drag in recovery.”

That’s consistent with research from July pointing to more people reporting “hardship in paying for regular expenses” in states that followed the path Reynolds chose for Iowa.

Despite Iowa’s mediocre economic performance, Reynolds may have sold a majority of her constituents on her narrative. The latest Iowa Poll by Selzer & Co for the Des Moines Register and Mediacom found that 57 percent of respondents approve of how the governor is handling the economy, 31 percent disapprove, and 12 percent are unsure. In June, a Selzer poll found Reynolds’ approval was 55 percent on the economy, with 36 percent disapproving and 9 percent unsure.