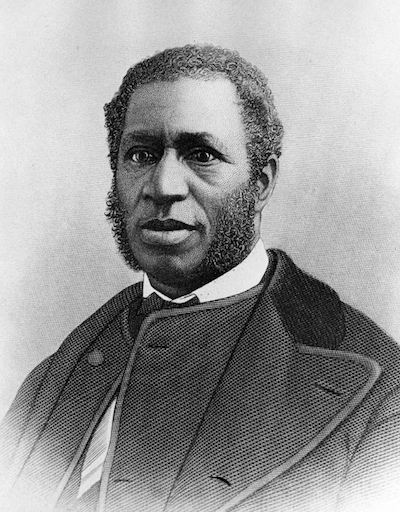

This column by Daniel G. Clark about Richard Harvey Cain (1825-1887) first appeared in the Muscatine Journal.

Researchers rely on the archived pages of the Muscatine Journal to reveal much of what can be known about our local history.

Whenever we honor Alexander Clark, we can thank the editor and publisher who led this paper for half a century. Clark starts appearing in John Mahin’s paper in 1857.

February 6: “We are indebted to A. Clark of this city for the proceedings … of a convention of the colored people of Iowa held here…. It was resolved to petition the Constitutional Convention to extend the right of elective franchise to native born negroes and to bestow upon them all the rights and privileges of citizenship.”

But then there’s this, on February 10: “A frame building on Seventh Street, near Iowa Avenue, was destroyed by fire last night. … Excepting the owners of the building, the one who will feel his loss most severely is Richard Cain, the pastor of the African M.E. Church, who occupied one of the apartments. Besides most all his household furniture, he lost a library worth not less than $150.”

That’s almost $5,000 in 2022. “The fire is supposed to have originated from some defect in the chimney.” There’s no suggestion of arson, but how curious that the pastor had just hosted a gathering extolled by historians as Iowa’s first of many “colored conventions.”

April 17: “Intolerance—The Tipton Democrat devotes over a column to the abuse of R. Cain, a colored preacher of Muscatine, who dared to address the citizens of Tipton on the subject of ‘Human Rights,’ one night last week.”

August 4: “The colored citizens of Muscatine, with a number from other parts of the State, met at the A.M.E. Church, at 10 o’clock A.M., August 3d, and with the Sabbath School connected with the Church, formed in a line and with the African Brass Band at their head, marched through the city to Hoops’ Grove, and listened with great attention to an oration delivered by the Rev. R.H. Cain, which was a masterly effort.”

The occasion was the congregation’s annual event celebrating the abolition of slavery in Jamaica in 1834. The report also mentions an address by “A. Clark”—long before he would gain renown as the Colored Orator of the West.

From the U.S. House of Representatives website: “In 1844, Cain entered the Methodist ministry; his first assignment was in Hannibal, Missouri. In 1848, frustrated by the Methodists’ segregated practices, he transferred to the African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church. Cain then served as a pastor in Muscatine, Iowa, where he was elected a deacon in 1859.”

Remember when President Barack Obama sang “Amazing Grace” at the memorial service for the victims of the prayer-meeting slayings at Charleston’s “Mother” Emanuel A.M.E. church? That’s the church Cain rebuilt in 1865. He was elected to the South Carolina legislature and then to Congress for two terms, and he was a newspaper publisher and college president.

Richard Harvey Cain—of Muscatine. Recall his name when observing Black history, when learning United States history—maybe relearning.

November 1877: “Hon. Hiram Price, our member of Congress, occupies a seat next to Richard H. Cain, a full-blooded negro member from South Carolina. Cain will be remembered by some of our old settlers as pastor of the African Methodist Church in Muscatine twenty years ago. He is a creditable representative of his race.”

June 1880: “Our fellow townsman, Alex. Clark, was highly honored by the late General Conference of the African M.E. church in St. Louis, which appointed him one of the twelve delgates from America to the Ecuminical [sic] Convention to meet in London in August, 1881. … Bishop R.H. Cain, formerly pastor of the A.M.E. church of Muscatine but now of South Carolina, is one of the alternates.”

Iowa’s equal-rights pioneer might have made his mark in the world anyway, but John Mahin’s increasing publicity throughout Clark’s career surely helped.

We learn from a 1911 county history that young John Mahin’s predecessor and mentor at the paper, Nelson L. Stout, “was an abolitionist and despite threats, despite the unpopularity of such a course in those early times in Mississippi river towns, openly and boldly denounced slavery.”

“From Stout he learned to fight for the principles he considered right, no matter what the cost,” wrote historian Irving B. Richman.

Is it coincidence that the Clark family plot at Greenwood Cemetary adjoins the Mahins? The Mahins share space with the family of John’s wife Anna, whose father was the Journal’s business manager, John B. Lee. And the Lees resided in Clark’s duplex at West 3rd and Chestnut.

Daniel G. Clark is not related to Alexander Clark but is proud to claim him as “brother by another mother.”