This column first appeared in the Carroll Times Herald, where Douglas Burns is the vice president for news.

In the 1960 movie “Inherit the Wind,” a signature piece of filmmaking that dramatizes the Scopes Monkey Trial, Spencer Tracy’s character, the attorney defending the teaching of evolution in schools, in very animated fashion delivers one of the best lines in cinematic history.

“Why did God plague us with the capacity to think?” says Tracy’s Henry Drummond. “Why do you deny the one thing that sets man above the other animals? What other merit have we? The elephant is larger, the horse stronger and swifter, the butterfly more beautiful, the mosquito more prolific, even the sponge is more durable.”

Drummond is the fictional character based on legendary defense attorney Clarence Darrow who squared off with populist/evangelist William Jennings Bryan in arguably the most significant debate in American history: the Scopes trial in 1925.

“Inherit The Wind” is one of Carroll educator James Knott’s favorite movies.

For more than a half century, Knott, a man who wanted to be a lawyer, but made the financially costly mistake of falling in love with teaching along the way, was the Clarence Darrow of the classroom in Carroll, Iowa. With changing turns of phrase to fit the generations he taught, Knott delivered a wonderful line of reasoning that cuts to the essence of teaching, and indeed life itself: Are you going to think for yourself, man, or are you just going to swallow what the more powerful or sanctimonious tell you to think?

Knott served as a Carroll High School teacher from 1961 to 1987 and then as dean-provost at the Des Moines Area Community College Carroll campus for nearly 20 years.

The Commons area in the new DMACC wing on the Carroll campus is named after Mr. Knott and his late wife, Marjorie, a long-time nurse in Carroll.

Thirty-five years ago at the my alma mater Carroll High, when I was backstage as an “actor” for the final play I would do with Mr. Knott as director, and the last play he would direct at CHS, he approached me and said he didn’t want any sentimental bull, any tributes to take away from the performance, which happened to be Huxley’s “Brave New World,” the tale of the divide between rich and poor run amok and one full of contemporary lessons.

I gave Knott my word then that we’d get our lines right and walk off the stage and move on to the next parts of our lives. That’s what he wanted.

If Knott knew I were writing this column, I can tell you what he’d say: “Burns, get on with it.” He might even call me a “dingbat” or some antiquated and endearing insult for good measure.

In other words, Knott would say, I have some more students to teach, and you, Burns, surely have more stories on other people that need to be told.

True enough. But we’ll have time for that tomorrow.

Knott gave students an outline of how to live their lives, how to challenge with respect, how to swim against the stream without being self-destructive (perhaps his greatest lesson). He wasn’t a captain-oh-my-captain schmaltz-king in the classroom like so many popular teachers today, but more of a pirate in the teaching fleet, always game for a fight with the establishment monkeys and purveyors of conventional wisdom.

Hollywood’s Mr. Holland taught kids to play trumpets and bang on drums. Knott taught us how to think. There’s no comparison.

He wouldn’t suffer grade-grubbing sycophants, and seemed to have more affection for the kids smoking cigarettes across Adams Street from the old CHS than the showcase students with their lists of activities and yearbook-ready smiles and Facebook-posting moms.

In CHS speech class one day, this kid who wasn’t a very good student and certainly was no stranger to detention (where I spent a lot of time, too), gave a demonstration of how to handle martial-arts devices that were admittedly often used to escalate the stakes in schoolyard fights.

A lot of teachers would have thrown this kid out of class, and in the post 9/11-Columbine world of zero tolerance, perhaps that would be the proper course. But the kid gave a great speech. He was passionate about the subject, knew his facts, and Mr. Knott gave him kudos for the presentation, told him it was far and way the best speech of the day. (It was.) I doubt the student, always one for the back rows of classes, ever had that kind of encouragement, ever felt that he was at the top of the class in anything. It was an enormously moving thing to see.

This community learned much from Mr. Knott about respect.

Years ago, in a conversation with former Carroll Middle School principal John Kinley, who went on to be the superintendent in Gilbert, I mentioned something I called “the one great teacher theory.” If a student has just one great teacher, I observed, it impacts the young person’s learning in other classes with lesser teachers because the kid is always measuring himself by the expectations of a Mr. Knott.

Kinley, one of the better administrators to come through here, didn’t disagree.

Many of us still measure ourselves by the standards Mr. Knott set. His former students refer to him with the proper salutation, “mister.” One wouldn’t call Franklin D. Roosevelt “Frank,” and those of us who sat in that classroom on the third floor of Carroll High School will forever refer to our teacher as Mr. Knott, as a show of respect for him and the respect he taught us to have for ourselves.

It is hard for me to think of a person in the community who has had such depth of influence on thousands of people: whether through teaching in the trenches of a worn-out high school building or by building a community college that makes higher education accessible to many western Iowans who would be left behind without Knott’s foresighted leadership.

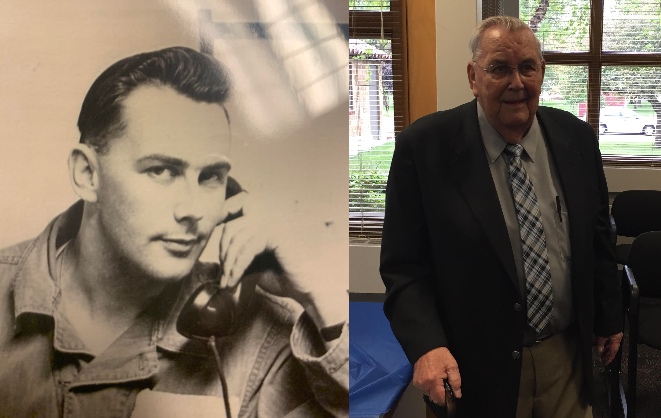

Top photos of Mr. James Knott provided by Douglas Burns and published with permission.

1 Comment

What a wonderful tribute

I hope that many Iowa teachers who deserve tributes will recognize themselves in this eloquent essay. Thank you so much, Douglas Burns, for writing and sharing it.

PrairieFan Thu 10 Mar 3:37 PM