Matt Hardin suggests five reforms to make voting easier in the U.S., modeled on how presidential elections are conducted in France.

I recently took a vacation to Paris and got to see French democracy up close.

While my wife and I were there, France held the second and final round of its presidential election, which is a simple runoff between the top two candidates from the first round.

On April 24 the incumbent president, Emmanuel Macron, soundly defeated the far right candidate, Marine Le Pen, 59 percent to 41 percent. One of the most reported-on figures in the French media was the abstention rate—the percent of registered voters who didn’t vote.

According to the French, the 28 percent abstention rate (so, 72 percent turnout) is an alarming sign for their democracy. Usually, only about 15 to 20 percent of French voters stay home.

Despite the hand wringing in France, the comparatively low abstention and high turnout stunned me. I wanted to understand how they do it.

In our recent presidential elections, the national turnout of registered voters is usually in the 50s. The 66 percent national turnout in 2020 was the highest in more than 100 years. Our turnout rate in Iowa is generally very good: usually in the 70s in presidential years. But it’s one thing to do that in a small state, and another to replicate that—or go even higher, into the 80s—across a diverse country of about 67 million people.

In some ways, French presidential elections are similar to ours. They vote for a singular national leader (rather than in a multiparty legislative election for parliament, which comes later). The election comes down to two candidates (two in effect for us, and two by law for them). Finally, many voters view their role as picking the lesser of two evils.

So, how can that country consistently have such high turnout?

The answers don’t map evenly onto our ideas about voter participation. Bleeding Heartland readers are likely left-of-center, as I am, and may find some of their rules surprising.

FRANCE MAKES VOTING, CAMPAIGNING HARDER IN SOME WAYS

France achieves turnout rates between 72 percent and 87 percent for its presidential elections. They do it without many voting rules that American liberals may assume are table stakes for a vibrant and accessible democracy.

First, France has many rules on voting times and voter requirements that would be considered barriers HERE.

- There is almost no absentee voting. My understanding is you can theoretically vote by mail if you’re in the hospital or a long-term care facility, but generally it’s unavailable. That’s a less forgiving standard than any state in the U.S. Most countries in Europe take the same approach, in fact. This also makes counting votes much faster.

- Likewise, there is no early voting. Election day is all they get. This is also the standard arrangement in Europe.

- Everyone must show a photo ID to vote. Even with growing communities of immigrants, people of color, and non-French speakers, the ID requirement is not especially controversial.

- The voter registration deadline was March 4 this year, or a little over a month before the first round of the election. That’s fairly similar to many states in the U.S., but a far cry from our same-day registration in Iowa. The traditional date up until this year has been December 31, so it used to be even more restrictive. Most democratic countries (and some American states, now) have automatic voter registration. France and most states in the U.S. are outliers here.

Second, there are rules that cut out the final few days of a campaign focused on persuading people to vote.

- There is nothing akin to a campaign’s get-out-the-vote operation—in fact, GOTV as we know it is illegal. In the final days before the election, there are strict rules on campaigning and election communication. No rallies, no door-knocking, no flyers, no calls, no texts. The idea is citizens should have a few days of sober reflection without unfair influence before casting their votes.

- The election basically vanishes from television news, also by law. Broadcasting poll results in the final days is illegal. When I was there, the news channels talked a lot about Ukraine, but almost nothing about the major election happening the next day or two. And during the six months before the election, political ads on television are illegal. They miss out on the joy of hearing “Je suis Emmanuel Macron, et j’approuve ce message” over and over and over again.

So, how is it possible to get such high turnout with all these restrictions?

IN OTHER WAYS, FRANCE MAKES VOTING EASIER, SIMPLER

France has a group of election rules that make voting fast, convenient, simple, and less intimidating.

The election is on a Sunday. As anyone who has visited Europe knows, most businesses and stores really do shut down on Sundays, so people have all day to go vote. Sunday voting also means that voters go at different times of the day, rather than a big crush of people after 5:00. So, you don’t get long lines of people waiting hours on a Tuesday night like in America. That makes voting less of an ordeal, especially for people with kids.

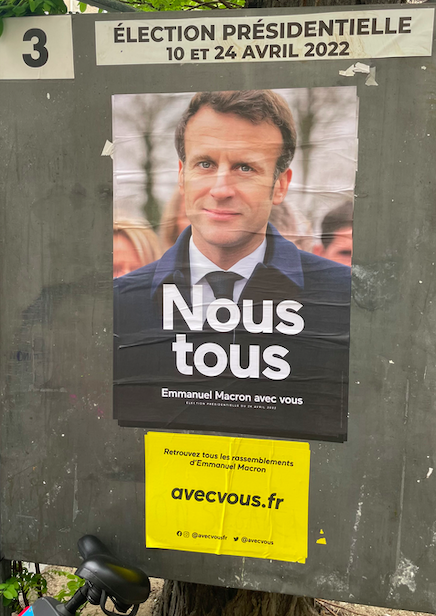

Presidential elections in France are for that office only. Casting a ballot takes very little time. Simplicity and speed make voting less daunting. The line that I watched for a bit at a school in central Paris moved quickly (photo below).

In the U.S., most places have at least a full page, front and back, of offices to vote for, from president to state judges to soil and water commissioners. Voters in California get a thick packet because of all the initiatives.

The ID cards needed to vote are free and, from what I understand, easy to get. There’s a clear list of accepted forms of ID, including a national voter card, so there is no controversy about certain IDs being accepted and others rejected. And because the information is already accurate and the cards are uniform, there’s no need for affidavits, provisional ballots, or scanning IDs, all of which suck up time and make lines longer.

Votes must be in person, but voters can send someone else to vote for them. It’s called procuration, or proxy voting. To do it, voters have to fill out a form before the election at their local police station and provide the name and voter number of the person they want as their proxy. About 7 percent of voters used that option in the last French presidential election in 2017.

WHAT COULD PRO-VOTING REFORMS LOOK LIKE IN AMERICA?

We don’t have to throw out absentee voting or early voting. But we can recognize that elections can be convenient and accessible without them—if we put other reforms in place. Proxy voting might be a little too off-the-wall for most Americans to accept. And we definitely couldn’t limit ads, rallies, poll publication, or GOTV operations, because that would run straight into the First Amendment buzz saw. But here are some things we could do:

Set Election Day on a Sunday. Sunday voting is the norm across Latin America and Europe. Congress can change the day of our elections with a simple bill—no constitutional amendment required. Failing that, we could instead . . .

Make Election Day a holiday. You’ve undoubtedly heard this one before. The key here would be to make sure most businesses actually close, rather than just use the day as a chance for sales (I’m looking at you, mattress stores) that require working class people who work in retail, food service, or hospitality to work all day anyway.

Enact automatic voter registration at the state or even federal level. We would join many other countries (not France) in doing it that way. Many people don’t pay attention to an election and decide to vote until after their state’s deadline has passed, so our registration laws create an unnecessary trap for the unwary. Iowa’s same-day registration model has worked well since 2008.

Cut down the list of items on the ballot. That would make voting faster and less intimidating, so more people would do it. Most of the ballot is for state and local offices, plus referendums and initiatives. In general, Americans vote for far more offices than our counterparts in other countries, and few people have any idea what most of them do or what the issues are.

Do we really need to elect five state offices, two state legislators, a county supervisor, five county offices, soil and water conservation commissioners, and hospital board trustees? That’s before we get to judicial retention elections, issue referendums, and city and school offices in odd numbered years. (I recognize not all these are on the ballot in presidential years, but the point stands—waiting to vote and filling out a ballot takes a long time, and is hard for a lot of people to follow.)

All those positions do important work, no question, but surely there is limited democratic value in electing every conceivable position when many races get almost no attention. Removing some may even require state constitutional amendments, like getting rid of judicial retention elections, which would be difficult but still worth doing if politically possible.

If we have to submit to voter ID laws, make it a free national system. We would need a uniform card with uniform rules for acceptance, to be sent to all Americans at no charge. I doubt that is politically feasible for a whole bunch of reasons, and it may well be a bad idea given the potential for disparate impact. But a national voter ID requirement was in theory on the table last year. Of course, actual voter fraud is nearly non-existent, and we have gotten along just fine without a voter ID requirement.

French democracy has its flaws. I’d rather live here than there. But, on the narrow question of maximizing participation, France and other countries with similar election laws show that it’s possible to get sky-high turnout in a large, multiracial democracy with laws that are simultaneously more restrictive and more accessible than those in the United States.

Matt Hardin is an attorney who lives in Des Moines. He has volunteered for and worked on Democratic campaigns since 2004, and he worked in the Iowa Senate in 2013 and 2015. He is interested in reforming political institutions so they are more representative of the public.

Top photo of a Macron poster provided by Matt Hardin and published with permission.

3 Comments

Interesting

One thing that makes elections in Europe far simpler is that they have FAR fewer races on the ballot. Like the French Presidential election, the UK Parliamentary elections are one race only.

A good example of how the number of races can slow voting down is the 2010 Florida election (IIRC). There were a large number of referendums (the ballot paper was 5 pages) and it took a long time for people to vote. This made for long lines.

BUT. Many people only will vote if the Presidency is on the ballot – turnout would collapse in many races if we had successive elections.

The First Amendment prevents some of the press limitations that exist in other countries with respect to elections.

Dan Guild Thu 5 May 10:59 AM

Should note

turnout in French local elections really struggles.

Dan Guild Thu 5 May 11:01 AM

Miller, Van Lancker, Pate?

It would be nice to get our candidates for SoS to comment here.

iowavoter Fri 6 May 6:38 AM