This column by Daniel G. Clark about Alexander Clark (1826-1891) first appeared in the Muscatine Journal.

I may have misled regular readers to suppose Muscatine’s early editors and lawmakers were a pretty progressive bunch.

Those anti-slavery and equal-rights figures are indeed appealing historical characters, and I confess I tell less about their opponents, mainly because I’ve learned less.

Alexander Clark’s publicist—my description for editor John Mahin—allied this paper with the Republican party when it emerged in the 1850s. There was almost always a Democratic paper in town, so he faced a procession of partisan competitors over his half-century career.

When one opposing editor attacked John A. Parvin, the 1857 Republican candidate for Iowa Senate, the Journal fought back.

September 26:

The editor of the Enquirer is shocked that Mr. Parvin should have declared in the Constitutional Convention that “the strength and power of the Democratic party is founded upon the ignorance of the masses of the people.” We knew this was an unpalatable truth, but we had supposed our neighbor was too discreet to stir up an investigation of its correctness.

Not all Dems, of course. “While the leaders, though usually well-informed, are unprincipled and deceptive, there are many who still cling to the party merely from prejudice.”

The Democrat editor was lawyer Edward H. Thayer. Along with being a newspaperman, he won election in 1857 as the county judge, which made him the top county administrator, too. Elected by “a majority of nine votes,” Mahin twitted.

The Democratic Enquirer, October 3:

The Democratic party are desirous of having the children of the blacks educated; but they solemnly protest against their crowding out the children of the whites. It is no use denying the fact that the whites will not submit to the idea of sending their children to the same school with the blacks. And if Parvin’s pet idea should become a law of the State, the result will be that the whites, though paying the school tax, will be denied the privilege of reaping any benefits therefrom.

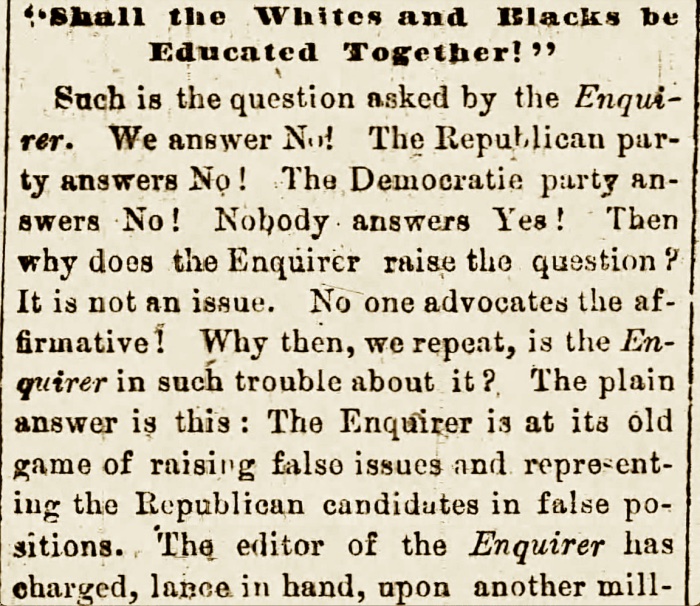

Muscatine Daily Journal, October 5:

The Enquirer is at its old game of raising false issues and representing the Republican candidates in false positions. The editor of the Enquirer…asks shall the whites and blacks be educated together? Now who says that they shall? We presume that the Enquirer refers to Iowa, and…we boldly assert that not a Republican candidate nor a Republican newspaper, nor any individual authorized to speak for that party, has advocated the education of white and black children together in Iowa.

Parvin lost his Senate race. Thayer continued editing the Enquirer (not as owner) before running his own successor paper from 1862 to 1872. And he rose in the ranks of his party, attending two national conventions.

Parvin, still a favorite target, hit back (Aug. 11, 1862): “Five years ago, when I was a candidate for Senator, E.H. Thayer, then writing for the Democratic Enquirer, published a number of falsehoods about me…. I do not intend to answer any more of Mr. Thayer’s lies or slander.”

A year later he was nominated for the Senate again, to fill a vacancy.

The Journal (September 7, 1863):

Let us roll up a heavy majority as well as elect our man. We care not who may be Mr. Parvin’s competitor, he must and will be defeated. … We don’t want any better man to beat the Muscatine copperheads with, because we know he will prove a prudent, careful Christian legislator.

“[S]uch a ‘Christian Legislator’ as a white man would like to see elected?” asked Thayer’s Courier (September 10). “To have one’s feelings completely wrapped up in favor of negroes, and have no heart for white brethren, is not exactly what is required of a ‘Christian Legislator.’”

The judge-editor sneered at “our friend…so highly esteemed by the abolition organ of our city.”

“The evidence to prove that Mr. Parvin is a negro-equality abolitionist, is abundant all around us. … Of course if Mr. Parvin should be the Republican candidate elected Senator, he would have an excellent opportunity to incorporate his peculiar views into the law of the State.”

Thayer drew a picture of “the negroes of Iowa jostling white men at the polls, crowding white children out of the schools, and occupying the jury box along side of white men….”

Parvin won this time and served in the Senate six years. And at last he would vote to delete the word “white” from the Iowa Constitution he helped craft in 1857.

Those editors sparred for fifteen years. Both claimed high ground, ridiculed the other’s typos and moral failings, accused the other of the worst abuses of civic decency and patriotism. They punctuated insults with faux apologies, mostly dead earnest yet sometimes almost friendly.

It’s tempting to guess how much of their rancor was for show, for circulation and ad sales, for scoring points with partisan bases. Can we judge from our distance?

Next time: Serranus Hastings revisited

Top image: From a Muscatine Journal editorial, October 5, 1857.