Anne Schechinger is Senior Analyst of Economics for the Environmental Working Group. This report first appeared on the EWG’s website.

A new EWG analysis has found that the overwhelming majority of Midwestern counties with increased precipitation between 2001 and 2020 also had growing crop insurance costs during that period due to wetter weather linked to the climate crisis.

In all, 661 counties got a crop insurance indemnity payment for excess moisture at some point during that period, adding up to $12.9 billion – one-third of the $38.9 billion in total crop insurance payments for all causes of loss in these counties.

This is the first analysis of the link between recent wetter Midwestern weather caused by climate change and rapidly ballooning crop insurance payments in the region for crops that have failed or been harmed by rain, snow, sleet and other wet weather – issues lumped together by the federal Crop Insurance Program under the term “excess moisture.”

The rapidly intensifying climate catastrophe has already increased the cost of the Crop Insurance Program in parts of the Midwest, and costs are likely to continue to go up without interventions that encourage farmers to adapt to climate change.

As currently set up, the Crop Insurance Program undermines the adoption of conservation practices like cover crops that can help farmers adapt to the effects of the worsening climate disaster, such as extreme precipitation events that are expected to continue occurring more frequently. It discourages such modifications by shielding farmers from the true cost of policies and minimizing the risk to the farmer of planting on marginal lands, among many other climate-unfriendly features.

The program has been heavily subsidized by taxpayers for many years, so as costs continue to rise, the American public will be on the hook, making reforms especially urgent.

Increasing precipitation in the Midwest

The Midwest has had significantly more precipitation in recent years. Annual precipitation amounts grew by between 5 and 15 percent between 1986 and 2015 compared to between 1901 and 1960, according to the Fourth National Climate Assessment. Depending on the year and location, this is due to more rain throughout the year, more frequent heavy precipitation events, or both. (These trends have continued since 2015, but that is the last year studied by the Fourth National Climate Assessment.)

EWG analyzed National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration data to evaluate which counties in the Midwest have seen increased annual precipitation. We found that, of the 738 counties in the Midwestern states of Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Ohio and Wisconsin, 683 had rising annual county-level precipitation between 2001 and 2020. (See Methodology for more information.)

The region is also expected to see more precipitation under the different projected greenhouse gas emission scenarios. Hotter warm season temperatures and periods of extreme rain followed by drought are likely across the region, which is predicted to have serious effects on agriculture.

Wetter weather leads to more excess moisture payments

Between 2001 and 2020, farmers in the eight Midwest states received almost $14.5 billion in crop insurance indemnity payments for reduced crop yields or revenue due to excess moisture and precipitation.

Indemnity payments are often made because of weather-related reductions in crop yield, so the Crop Insurance Program is inherently tied to the climate crisis. Nationally, excess moisture, precipitation or rain has been the second largest cause of crop insurance payments since 1995, smaller only than payments triggered by drought.

Some indemnities come from the money farmers pay, but additional payments – when losses exceed premiums – are largely funded by taxpayers. Premium subsidies are paid for solely by taxpayers.

Out of the 738 counties in the Midwestern states in our analysis, precipitation increased in 92.5 percent – 683 counties – between 2001 and 2020. And of those, almost 97 percent – 661 counties – got a crop insurance indemnity payment for excess moisture at some point during that period, with a total of $12.9 billion. This is 33 percent of the $38.9 billion in total crop insurance payments for all causes of loss in these counties.

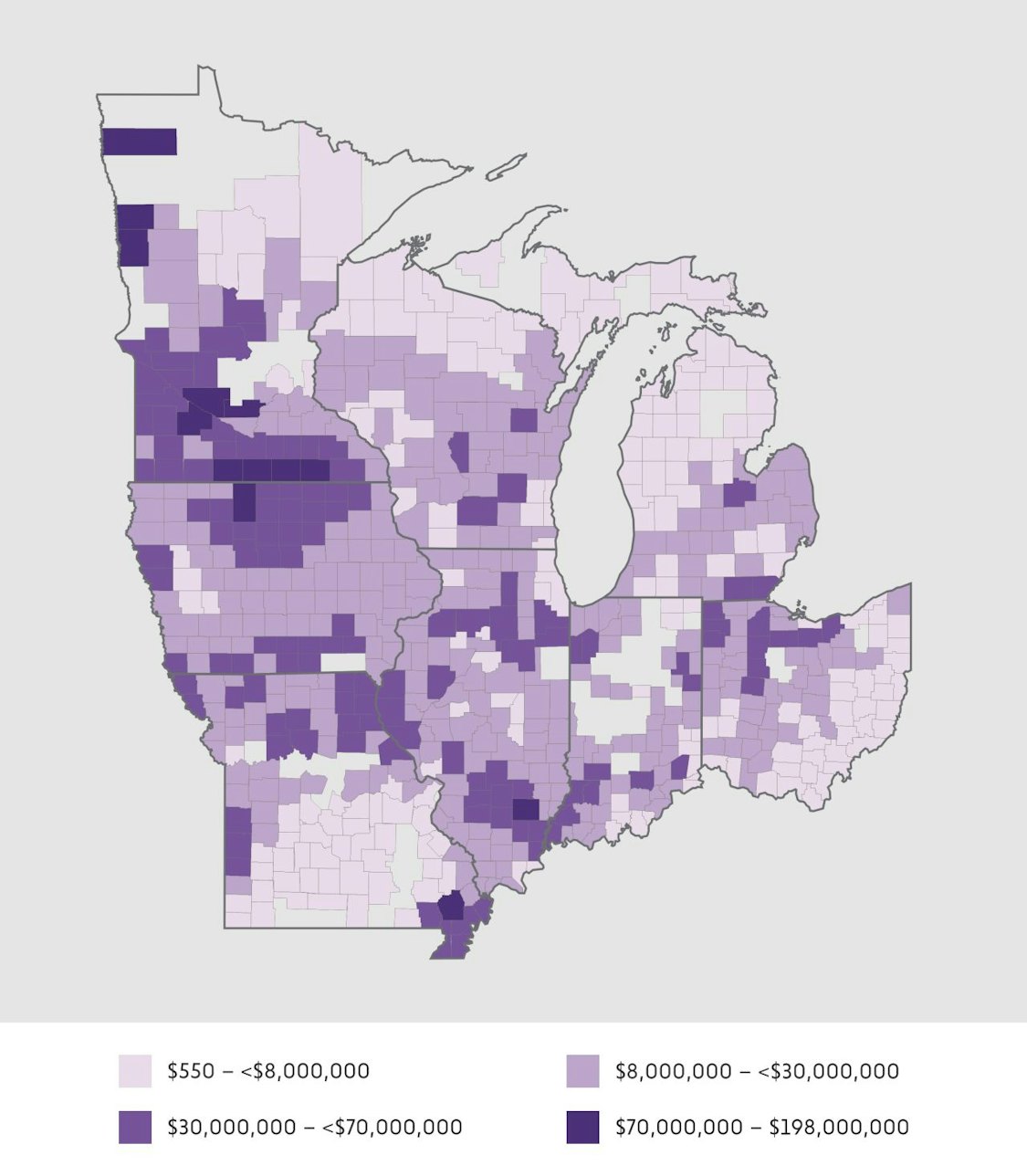

The map below shows the 661 Midwestern counties and their excess moisture crop insurance payments.

Source: EWG, from NOAA, Climate at a Glance and USDA Risk Management Agency, Cause of Loss Historical Data Files

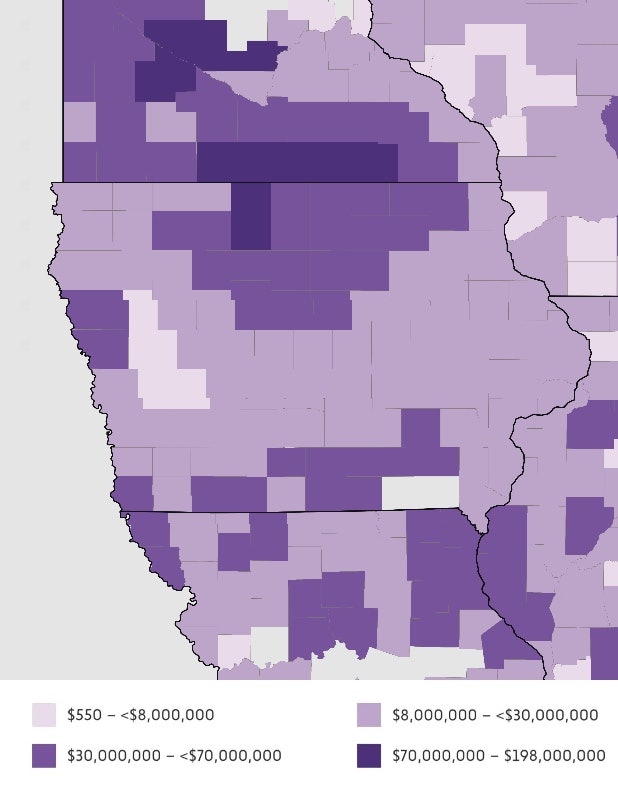

A closer look at the Iowa counties:

Excess moisture costs rose over time

Over the period we studied, excess moisture crop insurance costs – not just indemnities, but also premium subsidies, policies and acres – went up in nearly all the 661 counties that both had increasing annual precipitation and received an excess moisture payment.

The numbers are stark:

- 98 percent of counties had increasing excess moisture indemnities.

- 99 percent had increasing excess moisture premium subsidies.

- 95 percent had increasing excess moisture indemnified acres.

- 90 percent had increasing excess moisture indemnified policies.

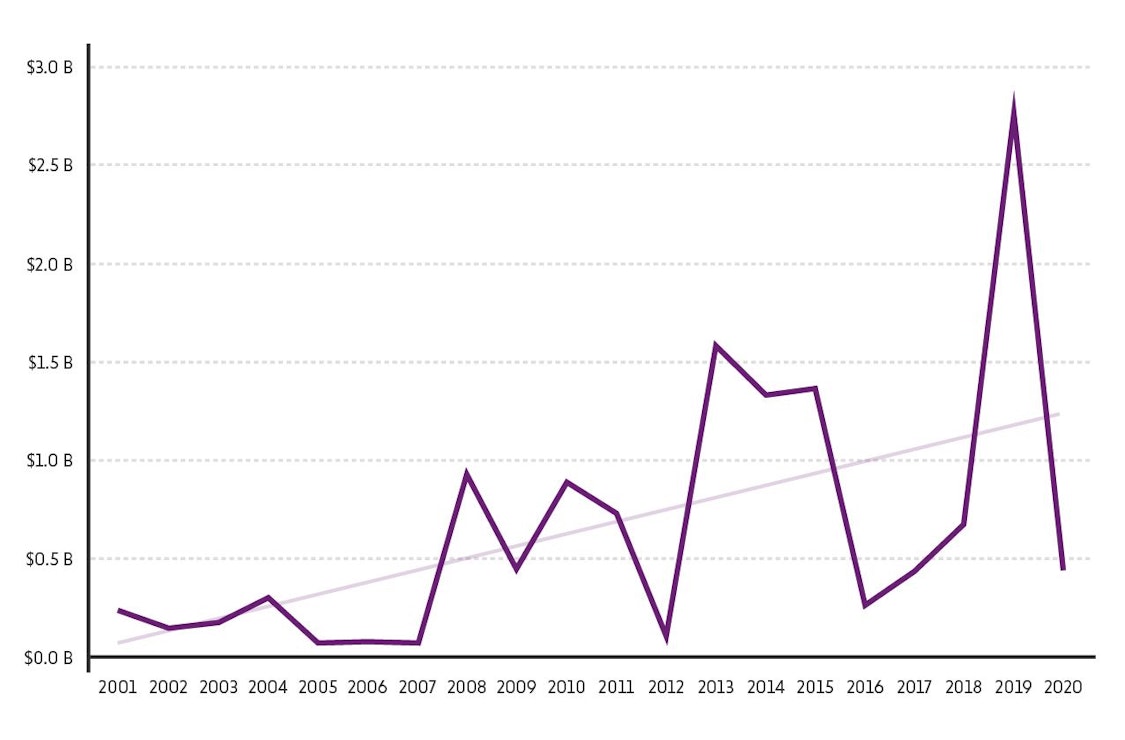

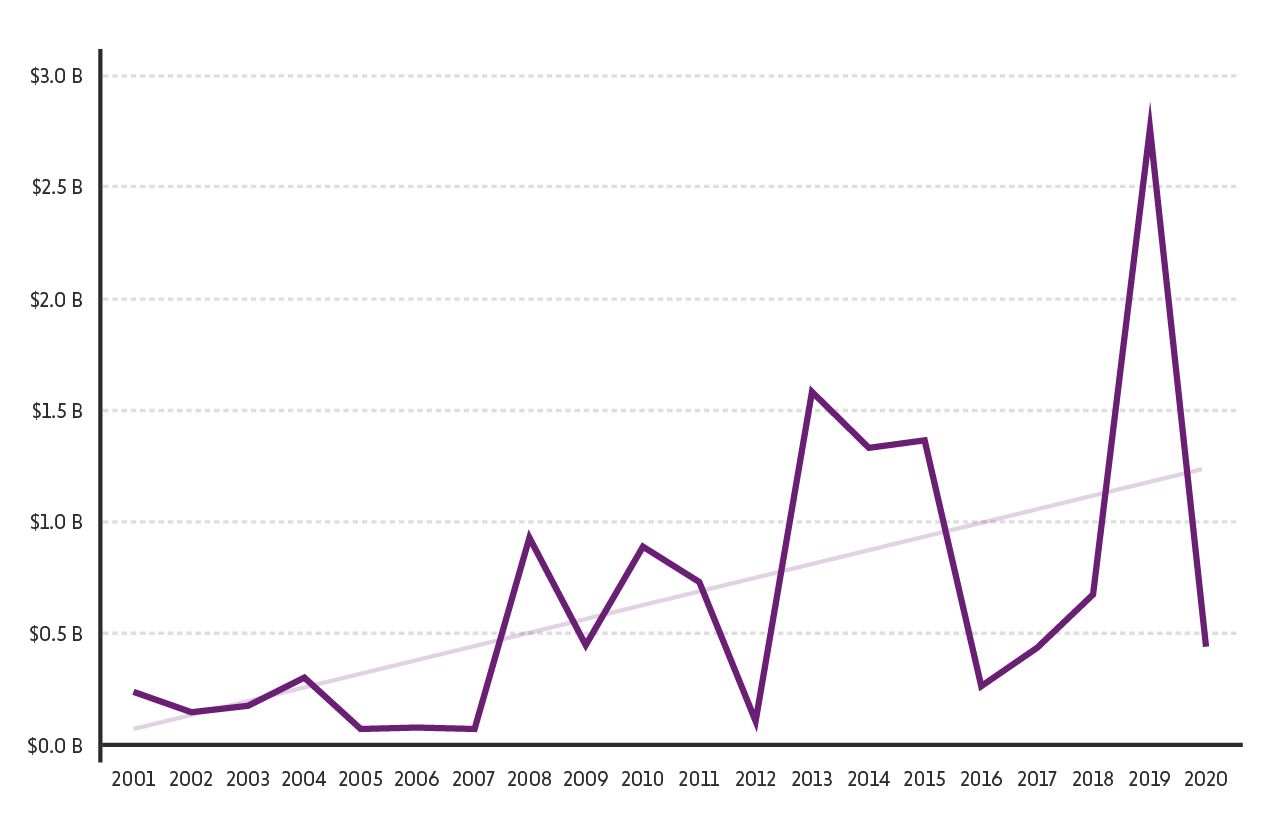

Figure 1. Excess moisture indemnities for the 661 counties that received payments went up between 2001 and 2020.

Source: EWG, from NOAA, Climate at a Glance and USDA Risk Management Agency, Cause of Loss Historical Data Files

During the period we studied, total crop insurance costs and program participation increased. But these two trends – alone or in combination – don’t explain why excess moisture costs have also gone up, because excess moisture as a share of the program’s total cost also grew.

In these 661 counties, excess moisture is becoming a bigger expense, compared to all causes of crop insurance losses:

- In 93 percent of counties, excess moisture indemnities went up as a proportion of total indemnities.

- In 88 percent, excess moisture subsidies grew as a share of all subsidies.

- In 94 percent, acres with excess moisture indemnities rose as a proportion of all indemnified acres.

- In 88 percent, policies with excess moisture indemnities increased as a share of all indemnified policies.

Crop insurance reforms to reduce costs and facilitate climate adaptation

Smart reforms to the federal Crop Insurance Program would both encourage farmers to adapt to the climate emergency and cut program costs, including premium subsidies funded in part by taxpayers. Possible reforms include:

- Reduce premium subsidies for the highest-risk farmers to encourage less production in these environmentally sensitive areas. Put some of the savings into easement programs these farmers can use to retire their cropland permanently.

- Factor recent weather events like drought, as well as projected weather, climate and crop yield data, into the premium rating process, instead of simply using 20 years of a farmer’s historical yields, and extend policies so they cover more than just one year. These changes could help encourage farmers to plan for the long-term, instead of basing decisions on the past.

- Require local agricultural experts, like extension agents who define “good farming practices,” to include many conservation practices in their guidance on what meets that standard. Or the USDA could create its own list of good farming practices and include conservation practices with proven ways to adapt to climate impacts and lower emissions.

- Change the subsidy structure to encourage more farmers to use the Whole Farm Revenue Protection policy, which can help promote crop diversification – a potentially useful adaptation technique – and is less costly for taxpayers.

- Eliminate the Yield Exclusion provision, which allows farmers in particularly dry or wet areas to ignore bad years when insurance guarantees are calculated.

- Reduce crop insurance coverage levels for the Prevented Planting provision in the Prairie Pothole region, since it encourages farming in wetland areas that experience excess moisture in most years.

- Limit total amount of premium subsidies each recipient can get and allow farmers to qualify only if their income falls below a certain threshold.

- Decrease premium subsidies for policies with the harvest price option, where insurance guarantees are based on the higher of the crop price either before planting or at harvest.

Editor’s note: please continue to the Environmental Working Group’s website to read the rest of the report, which explains how climate-friendly farming can help reduce crop insurance costs, and the methodology Anne Schechinger used to compile the data.

1 Comment

These are all great smart needed reform ideas...

…and some, if not most, have been discussed since I first started following Farm Bill politics in the Eighties.

Why do even the best and most obviously-needed Farm Bill reforms so often take forever to achieve? Why is Big Ag so politically resistant to needed change?

Here’s another idea that would help our ag-connected water problems at least a little. In Iowa, we could reform our outdated drainage laws so they don’t start out with the premise that drainage is always a public good. That premise was already dubious when Iowa drainage laws were written, decades ago. Today, that premise is bizarre.

PrairieFan Wed 26 Oct 1:28 AM