Silvia Secchi is a professor in the Department of Geographical and Sustainability Sciences at the University of Iowa. She has a PhD in economics from Iowa State University.

What’s a farm? Who is a farmer? These are political questions.

They are important questions for Iowa, as so much of the state’s identity is wrapped around its historical role in U.S. agriculture. The questions also matter for the U.S. Department of Agriculture, which implements policies that strongly favor Iowa’s farm and agribusiness sectors. The higher the number of farms, the more legitimate it is to keep claiming that “Iowa feeds the world.” Funding depends on that number too.

Joe Glauber, who used to be USDA’s chief economist, remarked in a Twitter exchange that inspired this post, “Hatch Act funding for experiment stations is determined, in part, by farm population of each state. So how one defines a farm has implications for that allocation.” He also recalled, “a frosty reception from Sen Byrd many many years ago when the Clinton Admin proposed to change the def from $1k to $10k. (WV would have lost a lot of farms).”

As that anecdote illustrates, politicians are of course the third category of people for whom the definition of a farmer matters.

IOWA FARMING IS VERY CONCENTRATED

So, how many farms and farmers are there in Iowa? Data from the last census of agriculture and a recent timely report from USDA’s Economic Research Service will paint a picture that will, I hope, help answer the question.

First of all, USDA defines a farm as “any place from which $1,000 or more of agricultural products were produced and sold, or normally would have been sold, during the year.” This means that zero-sales farmers are possible.

Indeed, Professor Nathan Rosenberg found (using micro data from the census that are not publicly available) that there “was a large increase in the number of zero-sales farmers from 104,000 in 1982 to 466,000 in 2012, as well as a remarkable rise in their share of the farming population, from 5 percent in 1982 to 22 percent in 2012. Women and minority farmers were disproportionately likely to be zero-sales operators: at least 30 percent of women, Native American, and black farmers reported no sales in 2012.”

We cannot separate the zero sales farms from very small farms in the publicly available data, but it is good to keep in mind that they exist. In 2017, there were 86,104 farms in Iowa. But according to the census, 11,530 (13.4 percent) of them were responsible for 75 percent of the sales. Conversely, a quarter of Iowa’s farms had sales of less than $1,000, and 43 percent of Iowa’s farms had sales of less than $20,000.

The picture is even more stark for livestock. For example, in the case of hogs, 2,567 facilities (about 42 percent of hog producing facilities) are responsible for 90 percent of Iowa’s hog sales. It is important to remember that Iowa generates one third of the total U.S. production, in part because regulation of Confined Animal Feeding Operations in the state is minimal, thanks to right to farm laws, “ag gag” laws, and lack of local control.

Iowa is also the biggest producer of eggs in the nation, with about 16 percent of U.S. egg sales. We have an inventory of 56 million layers in 4,425 facilities. But more than 99 percent of the Iowa “farms” in the egg business produce less than 4 percent of the eggs. I used to have a few chickens. Did that make me a farmer?

In fact, 96 percent of Iowa layers were in the 29 “farms” with more than 100,000 laying hens. Their average size is more than 1.8 million chickens. That is, 0.7 percent of the “farms” produce 96 percent of the eggs!

As an aside, besides issues with defining a farm, this concentration poses a huge risk to our egg supply, given the problems we have been having with avian influenza. At that size it is also impossible to do all-in-all-out management, which keeps flocks separated and is better for biosecurity and disease prevention. At the other end of the spectrum, 84.7 percent of the farms in the egg business had one to 49 layers, and were responsible for 0.11 percent of the egg sales in the state.

CHANGING DEFINITION INFLATED NUMBER OF FARMERS

To complicate the matter, in 2017 the USDA modified the definition of “principal producer,” allowing for up to four people to count, while before there was only one principal operator per farm, so we went from 88,637 principal operators in 2012 to 115,000 principal producers in 2017—even though the number of farms shrank to 86,104. Changing that definition also vastly boosted the number and percent of women in the principal producer category.

USDA’s report of farm typologies does not give an Iowa-specific number, but it divides farms by gross cash farm income (GCFI). Farms with less than $350,000 GCFI are further distributed into:

- retirement farms: small farms whose principal operators retired from farming, but continue to farm on a small scale;

- off-farm-occupation farms: small farms whose principal operators have a primary occupation that is not farming;

- farming-occupation farms: small farms whose principal operators’ primary occupation is farming. These farms are further subdivided into low-sales farms (GCFI of less than $150,000) and moderate-sales farms (GCFI between $150,000 and $349,999).

USDA states that at a national level, more than 11 percent of U.S. farms are retirement farms, and more than 37 percent are off-farm-occupation ones. Some of those operations are managed by people who would like to make a living on a small farm if they could, but others are likely taking advantage of the tax benefits of being considered a farm. It is likely than many are also happy farming and keeping their off-farm jobs.

Remarkably, Iowa State University only reports information on farm costs and returns for farms with at least $100,000 in gross sales. That’s only 39 percent of Iowa farms in the census, or 33,629 operations. Also interestingly, the net cash farm income for these operations is substantially higher than that of the average Iowan (the mean annual wage in 2021, same year as the ISU document, was $51,140), at over $153,000. The largest farms have a net cash farm income of over $311,000. Of course, as we just noted, one could have more than principal operator per farm, so we must be mindful of these differences in the comparison.

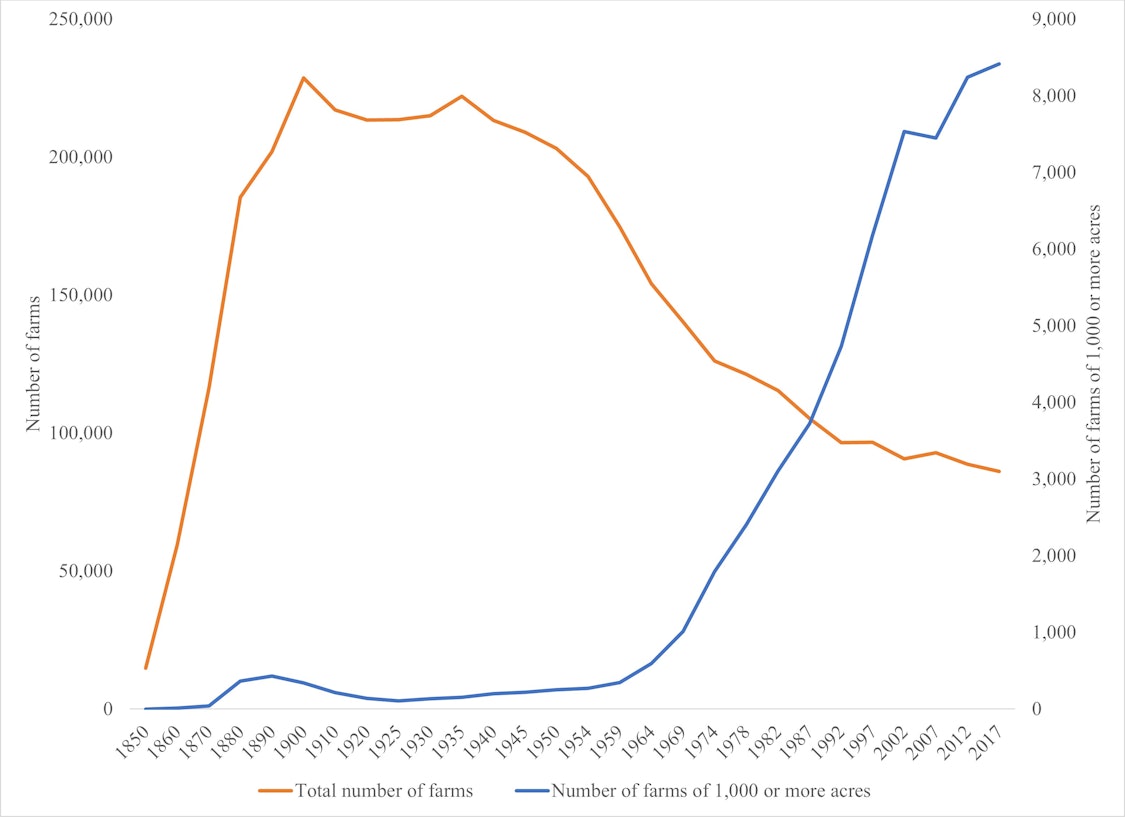

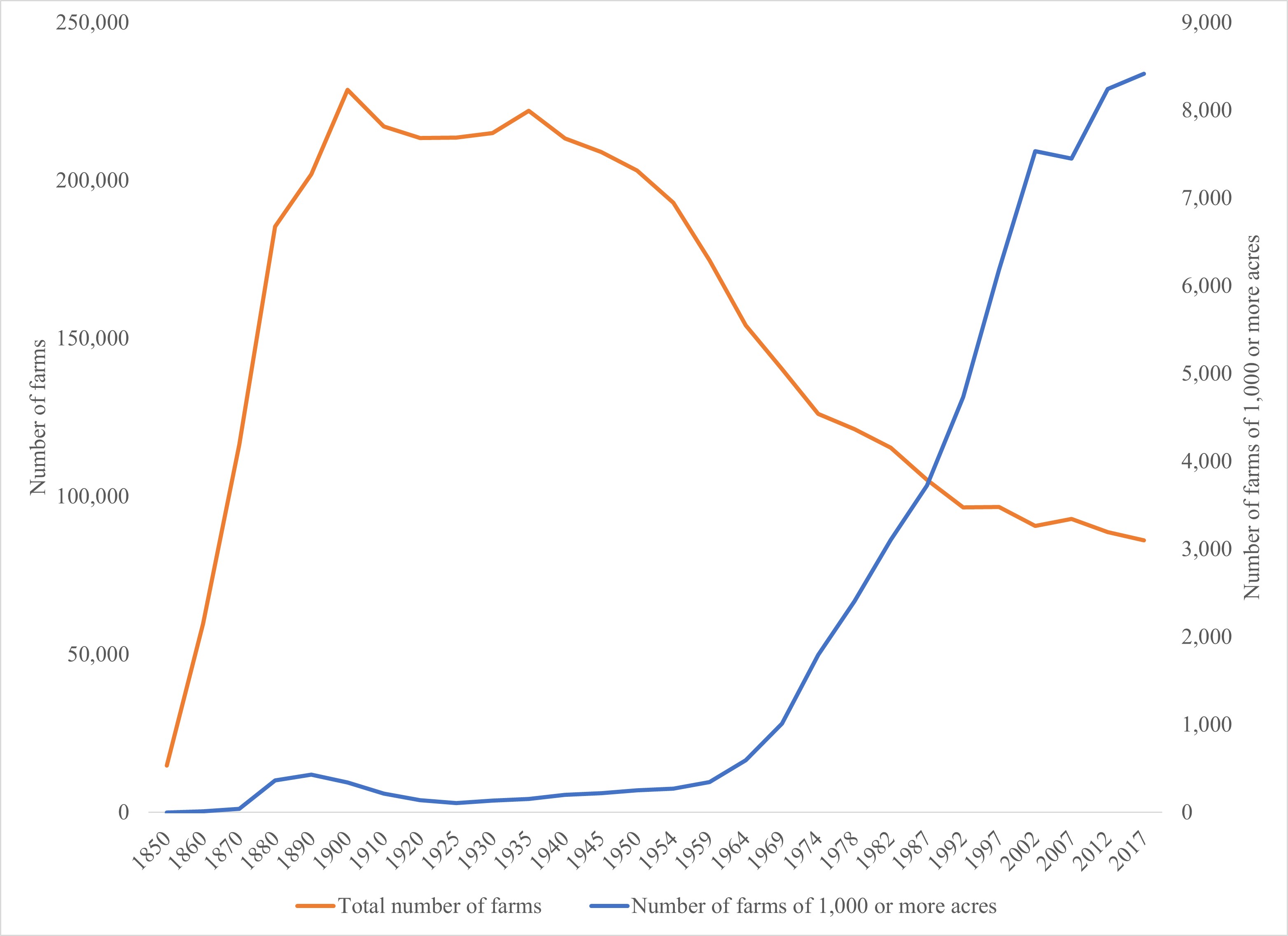

So, what kind of conclusions can we derive from this data? First, many benefit from boosting the number of operations and producers. It gives USDA a larger constituency, and it helps mask the speed of historical decline in the number of Iowa farms (see the figure below). Having lived in Iowa for almost 20 years now, I think this also plays into the sense of nostalgia that many in the state have for the old days of “family farms.” Politicians of both parties are more than happy to capitalize on that image and support “family farms.”

Source: USDA Census of Agriculture, dated from 1850 to 2017

“FAMILY FARM” NOSTALGIA SUPPORTS INEQUITIES

Alas, I must remind you that family farm is not a meaningful term in the U.S. Again according to the same USDA Economic Research Service report, “family farms accounted for about 98 percent of total farms and 83 percent of total production in 2021.” At least 91 percent of Iowa’s farms are “family farms,” that is family-owned operations or family-held corporations.

This nostalgia gives an oversized influence to an industry which is responsible for a lot of pollution and is very poorly regulated by both state and federal laws. The census masks how small and concentrated our farm sector has become, and how much richer farmers are, as a group, than the rest of the population. Ironically, farmers’ wealth is partly due to U.S. taxpayers: Iowa is first in the nation in corn production, number of hogs, egg sales, and subsidies.

It also does not help that Iowa State University, Extension, and USDA field offices (paid for by all taxpayers, I may add) benefit from circulating the larger numbers. There is clearly a conflict of interest between informing the public about the reality of the number of operations and inflating the size of the constituency they serve. Another contributing factor: farmers are overrepresented in the Iowa legislature.

This is not to say that there aren’t small farmers who are struggling and people who would like to farm and do not have the means do to so. In fact, their existence is being used to perpetuate a system that rewards large, polluting operations that crowd out alternative agricultural production systems. Smaller, more diversified, and beginning farmers who do not come from a farming background cannot compete with conventional large-scale operations that do not have to account for their pollution, and receive the largest share of subsidies by far.

The Environmental Working Group estimated that “In 2019, the richest 1 percent [of farms] received almost one-fourth of the total, and the top 10th received almost two-thirds.” Small-scale diversified farming operations are struggling, and every day is worse for them because of the policies we have in place. Industrial agriculture’s advocates defend those policies by invoking the past and strategically inflating the number of farmers.

WHY IT MATTERS

Being better informed about the characteristics of Iowa’s farming sector is important for the general public for several reasons. First, the numbers help convey that a small and shrinking numbers of very large facilities dominate Iowa livestock production, and those facilities could and should be regulated much more effectively than they are now (admittedly, that is a low bar). For example, the “Master Matrix process” for regulating CAFOs is a failure full of loopholes.

Second, the facts make clearer who our policies (including the subsidies) are supporting, and who they are hurting.

Third—and forgive me for the typical “further research is needed” academic trope!—the numbers points to a gray area we should investigate. How many of the farms in the small farms category (particularly those in the off-farm income category) could become full-time employment operations with the right form of support? How many of these farms exist mostly for tax purposes? What are the succession plans for retirement farms, and how can we promote access to land for those who want to farm, but do not come from a farming background?

In order to meaningfully answer those questions, we need to be frank about the problems large-scale operations cause.

Last but not least, I believe that painting an honest picture of Iowa’s farm sector shows how the agricultural lobby and politicians of both parties have pandered to Iowans regarding the supposedly central role the sector plays in our economy. Please let’s start by not saying ever again that agriculture is Iowa’s biggest industry (this report by Dave Swenson makes it abundantly clear, for example)!

The WPA mural at the top of this post conveniently ignores that the farmland so industriously managed was stolen from Native Americans, and that the Iowa Black Codes made it all but impossible for African Americans to buy land in the state as it was founded, with discrimination continuing to this day. Notwithstanding, that painting might have accurately depicted Iowa’s farm sector in the 1930s. It certainly does not represent Iowa’s agriculture today.

2 Comments

Important essay

This essay rebuffs myths about ag and farms that a city dude like me has always accepted as gospel. One thing I knew is that the number of tillable acres in the state is finite, and it’s per acre value (auction price) is going up while these acres end up in fewer hands. I believe the ”hands” are absentee landlords who own but do not operate the land (no doubt operated by immigrant labor). The lack of regulation of large scale CAFOs should be a wake-up for metro-area folks who get water from the south-bound rivers.

iowagerry Mon 19 Dec 5:46 PM

Thank you, Sylvia Secchi!

It is maddening to see Iowa’s current giant industrial-ag system, which is operating in ways that are so bad for soil, water, and biota, hiding behind an image of “family farming” that amounts to the equivalent of a giant cardboard cutout of AMERICAN GOTHIC.

Meanwhile, the Iowa Farm Bureau and like-minded allies coordinate a large PR machine that constantly spews out social-media messages explaining how “modern Iowa agriculture” is the epitome of wonderfulness. And then there’s the huge industrial-ag political clout that has blocked the development of even the most basic clean-water-policy needs in Iowa, like pollution standards and progress schedules and deadlines.

I’m grateful to know a few Iowa farmers and landowners who go out of their way to do really good conservation because it really matters to them. And determined Iowa experts like Sylvia Secchi also give me hope.

PrairieFan Tue 20 Dec 9:22 PM