This column by Daniel G. Clark about Alexander Clark (1826-1891) first appeared in the Muscatine Journal.

Lines by Lin-Manuel Miranda run through my head while I’m researching Iowans from the past.

“And when you’re gone, who remembers your name? | Who keeps your flame? | Who tells your story?”

More than a fine song in Hamilton: The American Musical, it’s a reminder of where history comes from.

What facts are important to remember—from whose point of view? Who is important to remember—and why? Who keeps their flames alive?

Last time I introduced mostly forgotten J.A.L. Crookham, who got his portrait on-screen for a moment in the film “Lost in History: Alexander Clark”—along with just enough narration: “State legislator John Lake Crookham moves to strike the word white from the Iowa constitution, and Clark’s campaign to get African-American men the right to vote finally succeeds.”

Ten seconds’ narration to sum up 1866-67 as “pivotal years in Clark’s life” and set the stage for his part in desegregating Iowa schools.

Crookham’s few seconds didn’t just happen, of course. No history gatekeeper chose him as avatar for Iowa’s post-bellum cohort of pro-Reconstruction lawmakers. That was left for his descendant who funded the film and a producer who agreed.

Intriguingly, Crookham receives zero mention in the histories I’ve been relying on for these columns. Not even Robert Dykstra, who weaves Clark into his narrative at critical points, calling him the state’s “most persistent civil rights activist.”

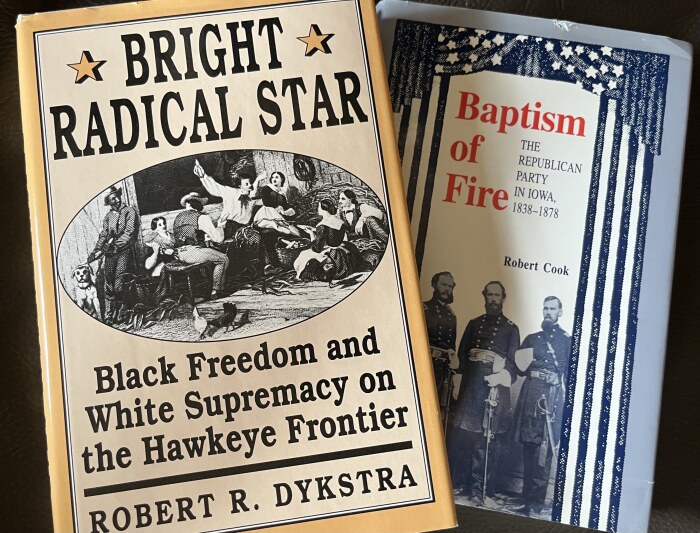

Last March I wrote: “If you care about how our settler forebears shaped the demography of present-day Iowa, find Dykstra.” I am still recommending his book I’ve quoted many times—Bright Radical Star: Black Freedom and White Supremacy on the Hawkeye Frontier.

In his chapter “The Egalitarian Moment,” Dykstra explains in detail the politics and demographics of “Iowa’s transformation from perhaps the most racially conservative free state in the Union into one of its most progressive.” But no Crookham.

Another excellent historian, Robert Cook, in a chapter on “Black Suffrage and the Intraparty Crisis of 1865-1866,” says: “Although the Civil War had not worked a complete transformation in the racial attitudes of local whites, it had taught many of them to respect the patriotism of American blacks and, equally significantly, to despise the activities of disloyal Southerners and Copperheads.” (Baptism of Fire: The Republican Party in Iowa, 1838-1878)

Plenty of examples of changed hearts and minds and votes, but no Crookham.

In August 1857 pragmatic centrists within the [Republican] organization had successfully neutralized the issue of black suffrage through their use of the referendum. Eight years later centrist Republicans combined with radicals at the state convention in Des Moines to initiate the process of expunging racial qualifications from the Iowa constitution. Although concerns over national Reconstruction policy may have played a part in this development, the key reason for the convention’s action was black loyalty to the Union during the war.

Cook, Baptism of Fire

It’s important to learn what happened in that June 1865 convention of white Republicans and thus to recognize the straight line to the October convention of Black veterans organized by Alexander Clark. Muscatine’s Henry O’Connor was a key player, and I read between the lines to believe Crookham was, too.

Reporting the various bills and amendments of the 1866 session, Cook concludes: “The legislature’s decision to initiate root-and-branch reform of the state constitution at a time when a cautious approach to the subject of civil rights might have been more expedient reveals the strength of the antislavery dynamic underlying early Republican policy.”

He quotes John N. Dewey, a Des Moines engineer and auditor of the Iowa War Fund, who observed that “we are making history fast and what would have been deemed radical two years since is cold conservatism now.”

No simple summary explains how profoundly Iowans changed in those pivotal years.

“The great struggle taught the public to read newspapers as it had never done before.” (History of Muscatine County Iowa, 1911)

At war’s end, the Muscatine Journal owner-editor John Mahin brought in popular war correspondent L.D. Ingersoll as co-publisher and editor. Maybe some Clark coverage and bold editorials I’ve ascribed to Mahin are attributable to Ingersoll who was also the author of a best-selling history of Iowa soldiers. For about two years he was a Muscatine resident and Republican county chairman.

Muscatine Journal, December 6, 1867: “The case of Alex. Clark vs. Independent School District of Muscatine was submitted on argument in the Supreme Court at Des Moines on the 5th. This is the case involving the right of colored children to attend the public schools.—It was decided in the affirmative by the District Court, last October, and appealed by the School Board. There is scarcely a doubt that the Supreme Court will sustain the decision of the lower Court.”

Along with rediscovering Alexander Clark, it’s high time we met our J.A.L. Crookhams and L.D. Ingersolls and other long forgotten egalitarians of Iowa.

Next time: Susan Clark in storybooks