Dan Piller was a business reporter for more than four decades, working for the Des Moines Register and the Fort Worth Star-Telegram. He covered the oil and gas industry while in Texas and was the Register’s agriculture reporter before his retirement in 2013. He lives in Ankeny.

Senator John F. Kennedy rose to a lectern at the Rice Hotel in Houston on September 12, 1960 to face the toughest audience of his presidential campaign; a roomful of Southern Baptist ministers who reflected the longstanding antipathy of the evangelicals toward Kennedy’s Roman Catholic religion.

JFK was just the second Roman Catholic nominee of a major political party, and older Americans remembered the fate of the first. New York Governor Al Smith lost to the lackluster Herbert Hoover in 1928, amidst charges that Smith’s Catholicism would put him—and the nation—under the control of the Pope in Rome.

If Kennedy didn’t win over the skeptical Texans, his sixteen-minute address at least neutralized their hostility by avowing his support for the longstanding doctrine of separation of church and state.

I believe in an America where the separation of church and state is absolute–where no Catholic prelate would tell the President (should he be Catholic) how to act, and no Protestant minister would tell his parishoners for whom to vote–where no church or church school is granted any public funds or political preference–and where no man is denied public office merely because his religion differs from the President who might appoint him or the people who might elect him.

Political historians consider JFK’s Houston address crucial. Two months later the senator from Massachusetts won the closest presidential election in U.S. history, by less than 100,000 votes out of 68 million cast.

JFK kept his promise to stay away from church-state issues; the only Catholic mass held in the White House occurred on November 24, 1963, before the president’s casket was carried out of the East Room for its trip to lying in state at the Capitol.

ORIGINS OF A DOCTRINE

U.S. Representative Mike Johnson of Louisiana climbed the dais in the House chamber on October 25 to take the oath as the body’s new Speaker. In his brief address after accepting the gavel Johnson declared “I believe that God has allowed and ordained each and every one of us to be here at this specific moment. This is my belief.”

That remark might surprise those who fought in America’s Revolutionary War and participated in debates that produced the Declaration of Independence and the U.S. Constitution. They created a democratic republic in 1787, based on the then-radical notion of representative government supported by consent of the governed. The founders had thrown off a British monarch who was head of his country’s official church and justified high-handed rule with the doctrine of “divine right.”

To make sure nobody missed the message, Thomas Jefferson and James Madison wrote in the First Amendment, “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof.” The amendment came on top of Article Six of their new constitution, which read “no religious test shall ever be required as a qualification to any office or public trust under the United States.”

The radical nature of what Winston Churchill later called the “Great Republic” can’t be fully appreciated today, with 247 years of experience living under the constitution written in Philadelphia. But in 1789, the notion of a nation without a God-ordained, church-sanctioned monarch as head of state was every bit as radical as Bolshevism would be considered two centuries later.

The doctrine of separation of church and state enabled the U.S. to escape the bloody sectarian wars that had rent both Europe and Asia. Because Protestantism has long been its dominant Christian practice, the U.S. avoided Roman Catholic authoritarianism (the chief fear of the Baptist preacher JFK addressed in 1960) in its government that often led to “strongman” dictatorships in Spain and South America.

CONSERVATIVES PUSH BACK

Polls have regularly shown that an average of two-thirds of Americans support separation of church and state. But an aggressive Christian conservative movement, touting freedoms of speech and religion, has pushed back.

Where the new Speaker Johnson once might have been an outlier for his blatant disregard for the separation doctrine, he has plenty of support in the current Congress. Representative Greg Steube of Florida posted a picture of Johnson and fellow Republicans kneeling in prayer in the well of the House chamber, commenting, “Mike Johnson is a strong conservative, but above all else, he is a strong Christian. He’s not afraid to look to his faith for guidance. America needs that more than ever in the U.S. House.”

Representatives James Burchett of Tennessee observed of Johnson’s ascension, “if you can’t see the hand of God in this, you’re just not lookin’—Mike Johnson is a sincere man of God, not one of these bumper sticker Christians.”

The U.S. has made a long spiritual/political journey since JFK’s speech that September day in Houston 63 years ago, and much of that passage was through holes in Thomas Jefferson’s self-described “wall” separating church and state.

The end of that journey is not yet in sight. Believers in a so-called “Christian America” want a return to what they call “traditional family values,” based on the “Judeo-Christian ethic.” Detractors fear that an officially Christian America is a one-way ticket to fascism.

THE SUPREME COURT ON CHURCH AND STATE

The doctrine of separation of church and state is just that and no more—a doctrine that isn’t specifically enunciated in the constitution and is periodically subject to judicial review. This was never clearer than in 2022 when the U.S. Supreme Court majority ruled in Carson v. Makin, requiring states to fund private schools, even if those religious schools would use public funds for religious instruction and worship. In Kennedy v. Bremerton School District, the same court also blessed a high school football coach in Washington State who knelt in prayer with his team on the field for a post-game prayer, ignoring the fact that the coach and the field were supported by taxpayer dollars.

Those decisions were historic enough on their own, but were quickly overshadowed by the Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization ruling, which overturned the Roe v. Wade decision that had established abortion rights in the U.S. for a half-century.

Both Dobbs and Carson came from a high court that by mid-2022 now counted six Roman Catholics among its nine members while Catholics constitute only about 20 percent of the U.S. population. The Roman Catholic opposition to abortion is central to its doctrines, and Catholic parochial schools had long coveted taxpayer dollars to cover ever-rising costs. In early 2023 the Iowa legislature obliged. Amazingly, the private schools scheduled to receive Iowa taxpayer largess would operate under virtually no state government oversight, financial or educational.

That seemingly breathtaking legal breakthrough occurred not by a prayer-driven miracle, but by an earthly merger of two strong religious forces. In 1960 Kennedy had faced Southern Baptist preachers deeply hostile to his Roman Catholic faith. The two denominations, while sharing a belief in the divinity of Jesus Christ, disagreed on just about every other theological point including the Papacy, the celibate priesthood, infant versus adult baptism, communion-based transubstantiation and the nature of forgiveness of sins.

There were cultural differences too. Catholics were centered mostly in big cities; evangelicals in the country. Catholics used real wine at communion, evangelicals grape juice (a sticking point that kept the two denominations at loggerheads during the Prohibition debate). Catholics listened to ethnic and urban swing music; evangelicals country and western. Catholics went bowling; evangelicals hunted and fished. Catholics had mostly worn blue in the Civil War; evangelicals Confederate grey.

It took the sexual revolution of the 1960s to put seemingly alienated Catholics and Southern Baptists, who became the theological pilot light for the larger evangelical Christian movement, together in a bed that was probably chaste but politically potent.

The sexual revolution was more than just movies and rock ‘n roll music. It was backed by science, law, and politics, starting with the advent of the birth control pill in 1960 and the Supreme Court’s endorsement of its use five years later in Griswold v. Connecticut. Other milestones: the Supreme Court’s 1967 decision in Loving v. Virginia banning state anti-miscegenation laws; the adoption of No-Fault Divorce by state legislatures beginning in 1969 (when the first such bill was signed by California governor Ronald Reagan, himself a divorcee); and the denouement, Roe v. Wade in 1973.

THE RELIGIOUS RIGHT EMERGES

After Roe, it was possible to think that America’s longstanding sexual prudishness, which was transplanted to the New World by the Pilgrims on the Mayflower, was finally dead. But not everybody accepted a new libertine America.

The seemingly polar opposite Roman Catholics and Southern Baptists, who together made up the largest block of American Christianity, discovered that for all their theological differences they shared similar views on sexual, reproductive and family issues starting with abortion and then same-sex marriage and eventually, the status of the transgendered. In all cases, they argued, scripture and church doctrine must take precedence over more modern sociological and psychological approaches.

The political realignment happened within a single presidential term. Jimmy Carter, a Southern Baptist from Georgia, could win the White House in 1976 despite carrying the anti-abortion doctrines of his faith. By 1980, Carter’s “pro-life” stance caused him a politically fatal erosion among Democratic women’s groups and liberals.

Meanwhile, Reagan opportunistically picked up the new “right-to-life” banner, declaring his opposition to abortion and telling an evangelical convention in Dallas “you can’t endorse me, but I endorse you” (a reference to the longstanding tax-exempt status of churches and religious organizations provided they remain aloof from partisan politics).

Reagan won the 1980 election in a walk and henceforth the new “Religious Right,” a coalition of politically-energized Southern Baptists and Roman Catholics, now had what they thought was a champion in the Oval Office. So, their frustration grew as Reagan, with an eye on public opinion polls, declined to push to overturn Roe, birth control, no-fault divorce, or most other cultural degenerations they abhorred. The best they got was U.S. diplomatic recognition of the Vatican, which had been opposed two decades earlier by the Catholic Kennedy.

Still, the Religious Right was here to stay. In 1988 and again in 1992, insurgent Presidential campaigns by Southern Baptist televangelist Pat Robertson and right-wing Catholic Patrick Buchanan pushed President George H.W. Bush and other “moderate” Republicans out of the GOP mainstream.

By 2000, when Bush’s son George W. campaigned in the Iowa caucuses, he showed a new side of the Bush dynasty when he told a Des Moines audience that his favorite philosopher was “Jesus Christ.” Church/state purists gasped, but Bush won the caucuses, the nomination, and the presidency. One of his Supreme Court appointees, Samuel Alito, would much later author the Dobbs decision overturning Roe v. Wade.

THE RISE OF SOUTHERN-INFLUENCED EVANGELICALS IN IOWA

The collapse of the economy caused by the subprime mortgage crisis of 2008 and the resulting election of Barack Obama had seemingly put evangelicals and their right-to-life movement out to pasture. But the seed of Iowa’s Republican religious revival was sown in 2007, when a Polk County District Court ruled Iowa’s ban on same-sex marriages unconstitutional. When the Iowa Supreme Court unanimously affirmed that decision two years later, Bob Vander Plaats went to work.

A gangly, once-time college basketball player at Northwestern College in the evangelical stronghold of Orange City, Vander Plaats began a school administration career but nursed an ambition to be governor of Iowa. He would be thwarted in the elections of 2002, 2006, and 2010, but found his groove as a political organizer, using the Iowa caucuses as his springboard.

Before the 2008 Iowa caucuses, Vander Plaats chaired the unlikely victory of Arkansas’ cornpone evangelical Mike Huckabee over John McCain. In 2010, he created The FAMiLY Leader, an umbrella group of fueled by evangelical Christian activists, and led a voter drive that ousted three Iowa Supreme Court justices over their decision on same-sex marriage.

Vander Plaats then endorsed the mundane Rick Santorum for president, who defied all odds to win a jumbled 2012 caucus race. Four years later, he brought home another unlikely Iowa caucus winner, Ted Cruz. The senator from Texas beat Donald Trump among Iowa Republicans, despite favoring Big Oil over ethanol producers.

By 2020, The FAMiLY Leader stood as the equal of the Iowa Farm Bureau as the central power in the state Republican Party. And while the Farm Bureau and gun groups focused narrowly on specific issues, Vander Plaats’ group broadened its reach into education and childcare matters.

To find his political shock troops, Vander Plaats mined the numerous startup evangelical churches that gradually supplanted the traditional mainline Methodist, Presbyterian, Lutheran, and Episcopal churches that long dominated Iowa’s Protestant Christianity. Many of those new churches bore nontraditional names such as Hope Church, Keystone church or Family church, but drew their funding from the traditional evangelical Southern Baptist and Pentecostal church conventions.

The new Iowa evangelical churches bore all the trademarks of traditional Southern Baptist practice; total immersion adult “believers” baptism, all-male clergy, a guarantee of forgiveness of sins and a “personal” relationship with a living Jesus.

Like their southern brethren, the Iowa evangelicals shared a taste for right-wing politics. Like Vander Plaats, they weren’t shy about taking on the church/state separation issue. Vander Plaats declared that the separation doctrine, far from being a protection for citizens who might be victimized by the combined powers of church and state, was written to protect churches. (Most constitutional authorities note that the separation doctrine was inspired by Jefferson and Madison who had seen Baptists, ironically, persecuted in Colonial Virginia when they preached against the doctrine of infant baptism mandated by the Church of England.)

Theological critics scoffed at evangelicals’ “cheap grace” and pagan-like worship of the human figure of Jesus as “King,” but evangelicals have proved to be an engine for Christian growth, partially (but not totally) offsetting the decline of the mainline denominations. Once an obscure, near-invisible corner of Christianity, evangelicals by 2022 amounted to near-equal status with the older mainline Protestant churches, each about 30 percent of the 77 percent of Iowans who identified as Christians. Roman Catholics made up the balance of Iowa Christianity, and Vander Plaats saw to it that the Family Leader maintained congenial relations with Christianity’s oldest denomination.

The rise of the Iowa’s southern-influenced evangelicals gradually turned Iowa into a colder weather version of the Old Confederacy, both politically and culturally. Like the Old South, Iowa became a one-party state politically based on the foundation of conservative “old time” religion plus low wages and ever-reduced taxes. Like the south, the new evangelical Iowa was more likely to ignore the tradition of separation of church and state.

None was more aggressive about breaching Jefferson’s Wall of Separation than Vander Plaats, who openly conducted faith-based “counseling” sessions with legislators in the state capitol and didn’t hesitate to crack the whip over recalcitrant lawmakers, as he did in 2022 when he endorsed primary challengers against five Iowa House Republicans who had failed to toe the line in favor of taxpayer subsidies for church schools.

THE NEW EVANGELICAL REPUBLICANS

Iowa thus has become what many think (or fear) is a model for the U.S. should Republicans win control of the White House and Congress to go along with the stranglehold they now hold over the Supreme Court. Calls for a “Christian America,” once considered ludicrous, now are mainstream among Republicans. The term “conservative,” which once applied primarily to economic philosophies, now is used more to describe a Republican political figure’s religious leanings.

Speaker Johnson may be the best personification of the new evangelical Republican. During his first campaign for Congress in 2016, he declared to an interviewer that Americans “don’t live in a democracy,” but a “constitutional republic,” adding, “And the founders set that up because they followed the biblical admonition on what a civil society is supposed to look like.”

When asked about his political philosophy in one of his first interviews after being elected speaker, Johnson replied, “Well, go pick up a Bible off your shelf and read it, that’s my worldview. That’s what I believe.”

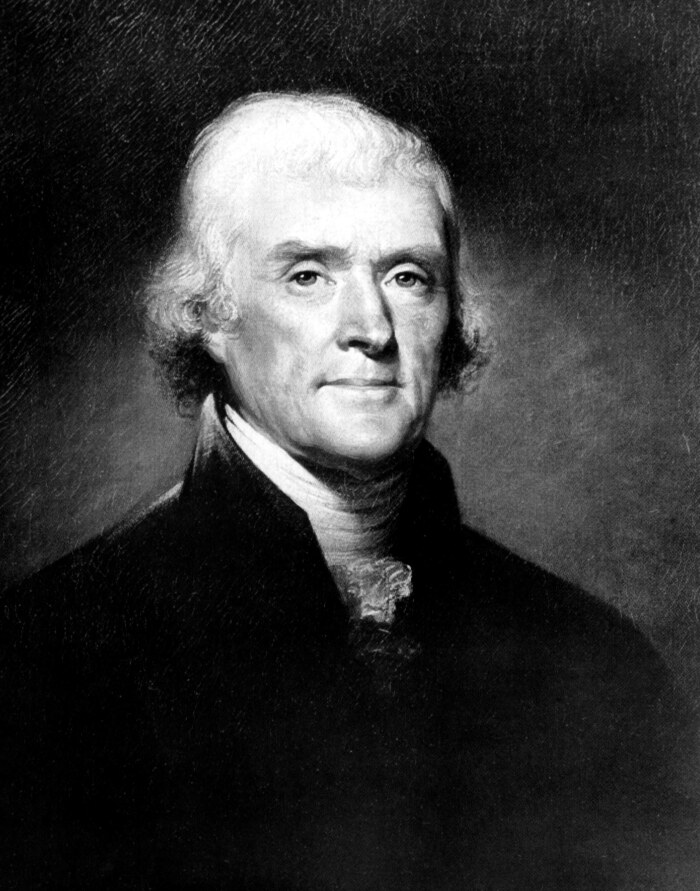

Top image: Portrait of Thomas Jefferson, by Rembrandt Peale, ca. 1810s. From the Everett Collection, available via Shutterstock.

3 Comments

Time to own Iowa as a center of White Christian Nationalism

Appreciate someone raising the issue but It’s been a two way exchange between the midwest and the south when it comes to the push for more overt Christian Nationalism and christian white supremacy was the rule since the ethnic cleansing that cleared the way for the settlers here, followed by lots of KKK from Indiana to lynchings in Omaha. As for the Catholic’s father Coughlin ran his christian fascist movement (and his CBS national radio show) out of MIchigan not Alabama, Rachel Maddow has an interesting podcast on how close he and his like came to making their move on our federal govt. so this isn’t new and the economics were always tied into the religious nationalism.

When helping to close an old Confederate Methodist Church in Memphis we found the notes one of the Methodist Women’s group took from a radio show they were listening to for moral support

from Nebraska calling out the commies behind the civil rights movement just as King was headed to support the striking garbage workers. And lets not forget that to this day it’s here that the presidential candidates come to kiss the rings of ministers and their financiers. Next time our Gov holds a state day of prayer with Steve King’s former chief and our acting AG by her side, let’s gather together to collectively say no…

https://www.weekendreading.net/p/hiding-in-plain-sight-the-sources

dirkiniowacity Sun 29 Oct 4:51 PM

I have close relatives in Michigan...

…who were students in the Sixties in a high school that was located only one mile from the National Shrine of the Little Flower. That is where Father Coughlin served as pastor during the years when he was reaching tens of millions with his broadcasts. But my relatives only learned about that piece of Southeast Michigan history when they were well out of high school. I wonder how that history is handled there now.

PrairieFan Sun 29 Oct 8:51 PM

indeed American education, especially history and civics, was never very good.

yes the good old days of education that everyone seems so nostalgic for were staggeringly whitewashed (really they rewrote our history to fit the post WW2 rise to power and wealth that we enjoyed while Europe was in ruins) and I don’t imagine things are much better now, of course if Christian Democracy devotee Betsy DeVos and her ilk get her way there (and of course here) they will probably resurrect him as a hero for the righteous cause.

dirkiniowacity Mon 30 Oct 10:55 AM