A federal judge will soon decide whether to block enforcement of all or part of an Iowa law that imposed many new regulations on public school libraries and educators.

Two groups of plaintiffs filed suit last month challenging Senate File 496 as unconstitutional under the First and Fourteenth Amendments to the U.S. Constitution. Among other things, the law prohibits school libraries and classrooms from offering “any material with descriptions or visual depictions of a sex act.” It also forbids schools from providing “any program, curriculum, test, survey, questionnaire, promotion, or instruction relating to gender identity or sexual orientation to students in kindergarten through grade six.”

U.S. District Court Judge Stephen Locher of the Southern District of Iowa did not consolidate the cases, which contain some overlapping arguments. But he did consolidate the hearings on the plaintiffs’ requests for a temporary injunction, which would prevent the state from enforcing certain provisions of SF 496 while litigation proceeds.

Near the end of that December 22 hearing in Des Moines, the judge said he will rule on whether to issue an injunction by January 1, when provisions allowing the state to investigate or discipline educators or school districts for certain violations will take effect.

Attorneys for the state advanced several misleading or contradictory legal arguments at the hearing and in briefs filed last week.

BACKGROUND ON THE CASES

Eight LGBTQ students and the advocacy group Iowa Safe Schools are challenging SF 496 in its entirety, with a focus on several areas: the new mandate on “age-appropriate” materials at all grade levels; the ban on content related to sexual orientation or gender identity from grades K-6; and provisions that require school staff to notify a parent or guardian if a student asks for an accommodation related to their gender identity. Bleeding Heartland covered the plaintiffs’ arguments in detail here. Click the links to read the plaintiffs’ initial filing, the state’s response and supporting affidavits (filed on December 19), and the plaintiffs’ reply to the state’s arguments (filed on December 21).

The publishing giant Penguin Random House, four best-selling authors, an Urbandale High School student and her father, three educators, and the Iowa State Education Association are challenging only the provisions of SF 496 that have led to books being removed from school libraries and classrooms. Bleeding Heartland covered that case here. Click the links to read the plaintiffs’ initial filing and brief supporting their motion for a preliminary injunction, the state’s response (filed on December 19), and the plaintiffs’ reply to the state’s arguments (filed on December 21).

A quick word on terminology: court filings from the various parties use different phrases to describe the same parts of SF 496. The LGBTQ plaintiffs, who are represented by the ACLU of Iowa and Lambda Legal, refer to the restrictions related to “age-appropriate” materials as the “all-ages ban” or the “book ban provisions.” Plaintiffs in the Penguin Random House lawsuit call that the “Age-Appropriate Standard,” and the state calls it the “Library Program.”

The first group of plaintiffs call the ban on instruction related to sexual orientation or gender identity from grades K-6 “don’t say gay or trans,” the second group of plaintiffs call it the “Identity And Orientation Prohibition,” and the state calls it the “Instruction Section.”

STATE BLAMES SCHOOLS FOR BANNING TOO MANY BOOKS

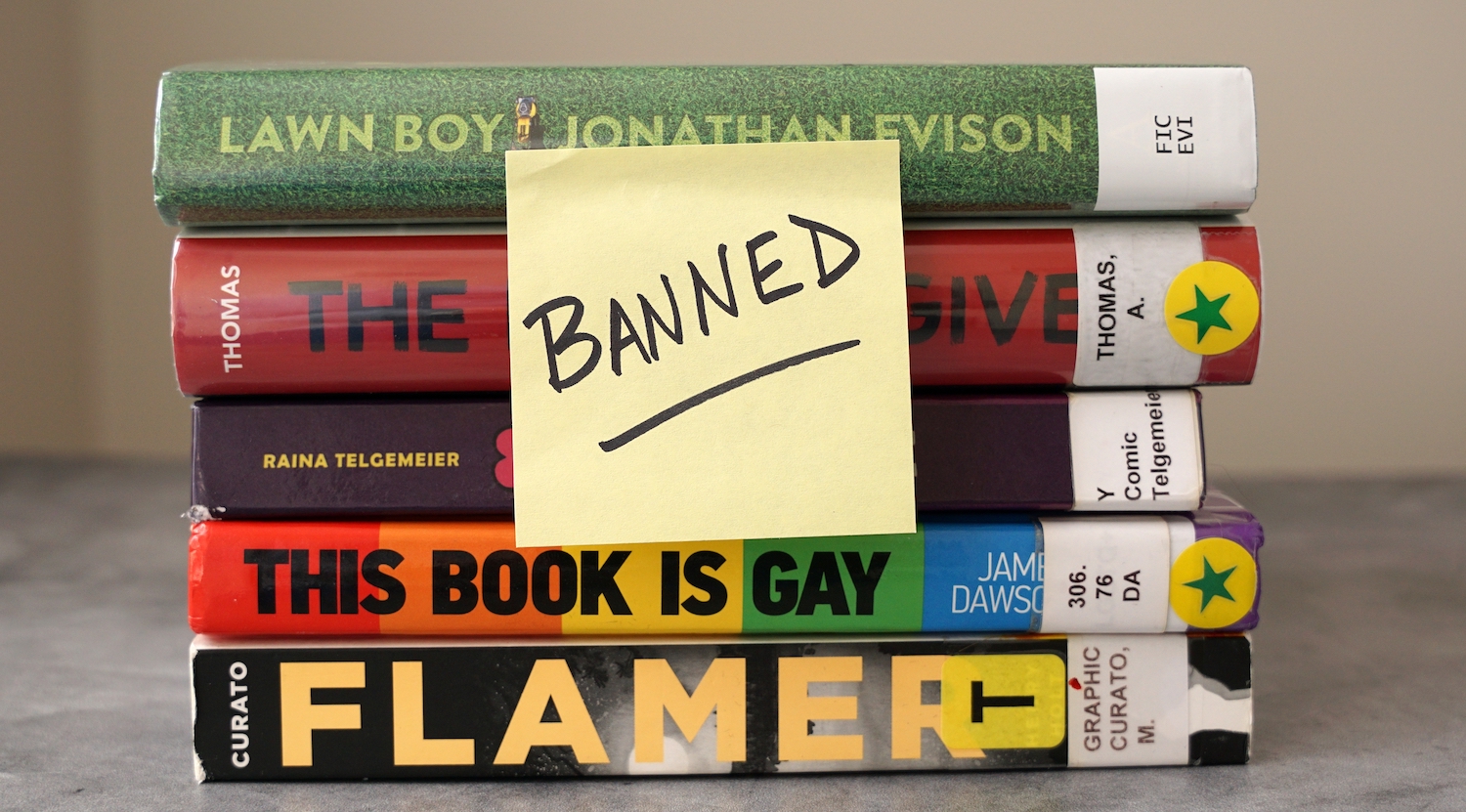

The Des Moines Register’s database indicates that dozens of Iowa school districts have removed hundreds of titles from libraries since Governor Kim Reynolds signed SF 496. Plaintiffs in both cases contend the law has deprived students of access to books with great educational or literary value. They have also highlighted the inconsistent decisions by various school districts as evidence the law’s book banning provisions are too vague and overbroad to be constitutional.

Assistant Attorney General Daniel Johnston argued in court that some school districts are reading the law with “tunnel vision” and pulling books that refer to people having sex without the “descriptions or visual depictions of a sex act” that the law prohibits.

The state fleshed out that argument in its written response to the Penguin Random House lawsuit:

When read in context and in conjunction with the definition of “sex act,” SF496 is clear on the detail a description must have to violate the Library Program.

The standard is clearer under the proposed [administrative] rules— “A reference or mention of a sex act in a way that does not describe or visually depict a sex act” does not offend the age-appropriate standard. […] Feigned confusion is not unconstitutional vagueness. School administrators and board members do not struggle to understand SF496.

In the same brief, the state argued, “Iowa Educators are not injured by a law that forbids them from providing books to school kids that depict sex acts. Their challenge concerns not the facial validity of SF496 or its proper enforcement but a misinterpretation of the law.”

Yet when Judge Locher asked Johnston about specific books that at least one school district has removed, or hypothetical books alluding to sexual misconduct by politicians, the state’s lawyer often declined to answer the question. He said he had not reviewed some of those works. He could not say whether depictions of sex acts in nonfiction books such as Elie Wiesel’s Holocaust memoir Night and The Rape of Nanking by Iris Chang would trigger the law’s provisions on “age-appropriate” material.

Speaking to reporters shortly after the December 22 hearing, Penguin Random House vice president and associate general counsel Dan Novack noted that the hundreds of books swept up by Iowa’s law include Pulitzer Prize winners. But when the judge asked whether schools properly removed those titles, “The state deferred and said they hadn’t read the books. That’s the problem.”

STATE CLAIMS SCHOOL LIBRARIES REFLECT “GOVERNMENT SPEECH”

Laws that restrict speech or expression based on content are typically subject to “strict scrutiny,” a difficult bar for the government to clear in litigation. Plaintiffs contend that SF 496 regulates content and viewpoints in many ways, causing irreparable harm to students, educators, book authors, and publishers.

The state appears to understand the law cannot survive strict scrutiny, because Iowa’s new restrictions on library books and curriculum materials are neither “necessary to serve a compelling state interest” nor “narrowly tailored” (using the least restrictive means) to accomplish that goal.

Instead, they want the court to apply the more lenient “rational basis” standard and declare the law constitutional because it serves the state’s legitimate interest in making sure children are not exposed to inappropriate content at school. The state’s brief describes that goal as “protecting children and delegating to parents the role of deciding when their children should be exposed to explicit materials.”

The state’s attorneys found one neat trick to show school library regulations don’t implicate the First Amendment. The state’s brief covers the “government speech doctrine” on pages 8 through 17. Key excerpts:

The State communicating its own message impairs no one’s First Amendment Rights. […]

No library can hold all books published, so a State must have authority to curate its public library collections. […]

As library composition is government speech, the State may set standards for how schools stock their libraries. State funded schools must be able to decide whether and how to stock sexually explicit material. […]

The First Amendment does not prohibit a State selecting materials based on content and viewpoint. […] And those decisions do not trigger the heightened scrutiny courts use to assess content- or viewpoint-restrictive decisions affecting private speech.

You don’t have to be well-versed in First Amendment jurisprudence to spot the flawed logic. The state of Iowa has never dictated library inventories to school districts. Local administrators and school boards control that process, relying on the expertise of librarians.

Even after passage of SF 496, the Iowa Department of Education and State Board of Education refused school districts’ requests for a master list of books that don’t meet the “age-appropriate” standard. Consequently, many districts have pulled books from the shelves—not because they didn’t want to provide them to students, but to avoid possible sanctions for educators and administrators.

Johnston tacitly admitted the state is not “communicating its own message” through the school districts when he blamed some districts for removing more library books than the law requires.

No one has asserted school libraries must stock every published book—only that the state can’t use content- and viewpoint-based criteria to mandate the removal of books schools previously chose to make available.

The reply brief on behalf of Iowa Safe Schools and the LGBTQ students notes that the state’s line of reasoning ignores “a half century of precedent establishing that students enjoy free speech rights in school settings.”

The reply brief for plaintiffs in the Penguin Random House case dismantles the “government speech” argument on pages 4 through 7. Excerpts:

The State Defendants’ attempted defense of the Age-Appropriate Standard boils down to one argument: that the First Amendment has no application whatsoever in school libraries. Every court that has ruled on this argument has rejected it, including in decisions in the past year3 and by federal district courts4 and circuit courts5 throughout the country.

The government speech doctrine applies only where (1) the state has historically “communicated messages” through the medium; (2) the medium is “closely identified in the public mind” with the state such that the government “has endorsed that message,” and (3) the state directly controls “the messages conveyed” through that medium. […]

Collections of books in school libraries do not satisfy any of the three factors.

Of the cases the state cites to support their government speech argument, only one “has anything to do with libraries”: U.S. v. American Library Association (relating to public libraries using software to block obscene material on internet terminals). “Contrary to the State Defendants’ suggestion, that case did not rule that library collections are government speech; it did not even mention the government speech doctrine.”

Novack told reporters the state is making “an incredibly extreme argument. It’s never been advanced before.” Every time the U.S. Supreme Court or lower courts have encountered this question, Novack said, “they have said the First Amendment does apply in libraries.” Taken to its logical extreme, the state’s “dangerous position” would mean the government could ban libraries from stocking books about Republicans or Democrats.

ACLU of Iowa attorney Thomas Story, who argued on behalf of plaintiffs in the first lawsuit, told reporters after the hearing, “If this were government speech, then the government could remove every book, everything from your kids’ libraries, and that’s not at all consistent with the constitution.”

STATE PRETENDS LAW BANS ONLY “OBSCENE” OR “GRAPHIC” MATERIALS

Reynolds and Republican lawmakers who helped draft SF 496 have asserted the law only bans “pornography” or “sexually explicit” material. When Judge Locher asked Johnston whether the “government speech” doctrine means the state could order every book to be removed from a school’s library, the state’s attorney countered that SF 496 doesn’t do that—it only forbids books with “graphic” descriptions of sex.

No matter how many times state officials repeat this talking point, SF 496 doesn’t contain the terms “pornography,” “sexually explicit,” or “graphic.” (Iowa House GOP legislators tried to add “graphic” to the definition of age-appropriate materials, but the Senate removed that word from the final version of the bill.)

Nevertheless, the state’s attorneys rely on this sleight of hand, arguing in a brief,

The Library Program shields school-age children from exposure to sex acts in the school environment. And it reflects other Iowa law that has long forbade “dissemination and exhibition of obscene materials to minors.” Iowa Code § 728.2. “Obscene materials” includes the same definition of “sex acts” used in SF496. […]

Keeping sex acts out of school libraries is reasonable. Fraser, 478 U.S. at 684 (recognizing “limitations on the otherwise absolute interest of the speaker in reaching an unlimited audience where the speech is sexually explicit, and the audience may include children”). That is especially true in school libraries hoping to educate youth.

The reply brief from Penguin Random House and co-plaintiffs slammed the state’s “misleading” attempt to conflate SF 496 with obscenity guidelines. “To the contrary, Iowa’s longstanding obscenity law illustrates the difference between a constitutional content-based restriction and a blatantly unconstitutional content-based restriction.”

Iowa’s obscenity statute uses language similar to the U.S. Supreme Court’s three-part test in Miller v. California (1973). An obscene work must (1) “appeal to the prurient interest in sex” as a whole, (2) “portray sexual conduct in a patently offensive way,” and (3) taken as a whole, have no “serious literary, artistic, political, or scientific value.” In contrast, SF 496 excludes any book that depicts a sex act, regardless of the work’s value as a whole or the student’s age and maturity.

Judge Locher zeroed in on the distinction at the hearing. While questioning Johnston, the judge noted that SF 496 is “way more restrictive” than an obscenity standard, and wanted to know whether certain books removed from some school libraries have literary value.

STATE IMPLIES “DON’T SAY GAY/TRANS” NEVER APPLIED TO LIBRARY BOOKS

Even before Reynolds signed SF 496 in late May, leaders of the Iowa Association of School Librarians and Iowa Library Association sought to clarify some aspects of the law with the director of the State Department of Education. For instance, librarians wanted to know whether “classic literature that is part of the Advanced Placement curriculum for AP Literature and Composition” would now be illegal in Iowa schools. And they wondered: would the ban on “programs,” “curriculum,” “promotion,” and “instruction” regarding sexual orientation and gender identity in grades K-6 “include the contents of library books, book displays, or book recommendations that relate to gender identity or sexuality?”

State officials opted not to answer those and many other questions before the new school year began in August. The State Board of Education’s proposed administrative rules to implement SF 496 also did not clarify whether school libraries could continue to stock books with LGBTQ themes.

Some school districts, such as Norwalk (among the defendants in the Penguin Random House case), have removed library books deemed to violate the don’t say gay or trans provision in schools serving students up to sixth grade.

The state now suggests it was all a misunderstanding.

From a brief filed with the U.S. District Court on December 19: “The Instruction Section does not apply to the Library Program because it does not apply to noncurricular books on library shelves. The Instruction Section concerns ‘prohibited instruction’ in the compulsory school environment. […] But a noncurricular book may remain in the school library under the Library Program, so long as it does not describe a ‘sex act,’ and it is age appropriate.”

Johnston confirmed during the December 22 hearing that the ban on instruction related to sexual orientation or gender identity does not apply to library books. When Judge Locher asked whether an elementary school student could choose to write a report about a book with a gay character, Johnston said yes. But he indicated that SF 496 would forbid a teacher from using a book discussing sexual orientation as part of curriculum by reading it to an entire elementary school classroom.

After the hearing, attorneys for both sets of plaintiffs emphasized that the state had refused for six months to explain the interaction of those provisions of SF 496. And Story told reporters that as of December 22, the Iowa Department of Education had not provided any written guidance to school districts, stating that elementary school libraries could continue to carry books with LGBTQ themes.

STATE CLAIMS TEACHING RESTRICTIONS ARE “NEUTRAL”—BUT NOT REALLY

Plaintiffs represented by the ACLU and Lambda Legal assert that SF 496 “violates the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment” by “discriminating against Plaintiff Students and other LGBTQ+ students based on sex, sexual orientation, gender identity, and transgender status, both facially and as applied.”

The state disputes that the law creates any “gender-based classification.” Johnston argued in court that the plaintiffs’ equal protection argument is “an overreaction based on a mischaracterization of the law.”

Here’s how the state lays it out in its December 19 filing:

SF496 neutrally allows classes regarding human sexuality to begin around the common point of puberty. See SF496 § 16. It also neutrally proscribes instruction on “sexual orientation,” whether gay, straight, or otherwise. See id. (defining “sexual orientation” as “actual or perceived heterosexuality, homosexuality, or bisexuality”). So age appropriate sexuality teaching remains the same regardless of the sex, sexual orientation, or gender identity of the students.

The LGBTQ plaintiffs’ reply brief points out the obvious: “If the law were intended to be applied neutrally, all books and curricular content containing any pronouns or mention of different-sex relationships would be excised from K-6 classrooms under the don’t say gay or trans provision.”

In fact, one of the questions the library associations posed to the state director of education in May was: “Does gender identity or sexual orientation standards include the full spectrum of expression including heteronormative content?” They didn’t get an answer.

Affidavits the state offered portray positive messages about LGBTQ people as a problem the law was designed to solve. Jackie Abram complained in her declaration that when her son was in eighth grade, a teacher admonished him for referring to a transgender classmate with female pronouns, instead of the classmate’s preferred male pronouns. Abram was also upset that her youngest son’s fifth-grade teacher read a book about a transgender child to the class.

An affidavit from Courtney Collier cited a survey that “asked students to rate their comfortability with their sexual or gender identity on a scale of one to five.” Similarly, Collier objected to the school librarian telling a class of fifth-graders “that they could read a book about a little boy close in age to the students who was struggling with his gender identity and sexual orientation.”

In dialogue with Judge Locher, Johnston appeared to confirm it would violate the law for a teacher in grades K-6 to read a book with gay characters to the whole class. There was no suggestion it would violate SF 496 for a teacher to read the class a book with straight characters and traditional expressions of gender identity, such as Ramona Quimby deciding she will marry Henry Huggins one day, or Henry Huggins and his friends building a “no girls allowed” clubhouse.

While questioning ACLU attorney Story, the judge sounded sympathetic to the idea that the law contains neutral language: it may be “one of the most bizarre laws I’ve ever read in my life,” he said, “but it is content neutral.” He floated the idea of reading the law to mean elementary schools cannot provide separate bathrooms for boys and girls.

Story characterized that interpretation as absurd. (A well-known concept in statutory interpretation is the law isn’t supposed to produce absurd results.) He assured the court that this legislature wasn’t trying to abolish boys’ and girls’ bathrooms. Clearly they were not, because in March, the same Republican lawmakers and governor enacted a “bathroom bill” forcing students, staff, and visitors to use only school restrooms and other facilities consistent with their “biological sex” as listed “on a person’s official birth certificate.”

Later in the hearing, the judge asked Johnston whether the state would want SF 496 enjoined if the court reads it to mean elementary schools cannot provide sex-segregated bathrooms, or separate boys’ and girls’ basketball teams. (Both could be construed as programs or instruction “relating to gender identity.”) The state’s attorney replied that the law doesn’t intend “absurdities.”

The judge followed up by asking whether he should look at state legislators’ comments—some of them quite “viewpoint specific”—when trying to discern the law’s meaning. Johnston did not concede that point, urging the judge to look only at the law’s text.

The upshot is that SF 496 is anything but neutral. In the plaintiffs’ words, “On its face, the law targets the subjects of sexual orientation and gender identity, and its purpose and effect is to chill and restrict LGBTQ+ content and expression.”

Which brings us to the most egregious gaslighting the state has brought to the table.

STATE CLAIMS LAW DOES “NO HARM AT ALL” TO LGBTQ STUDENTS

To persuade a court to block enforcement of a law, plaintiffs need to show (among other things) that they will be irreparably harmed if the law remains effect.

According to an affidavit from Iowa Safe Schools executive director Becky Tayler, SF 496 “has had a devastating impact on LGBTQ+ students across the state.” Some students are experiencing more bullying and harassment, or feelings of rejection and hopelessness. The organization is documenting a “notable, perceivable increase in completed suicides,” and its staff have been forced to spend more time and resources “dealing with the fallout and confusion over SF 496.” (Iowa’s Republican trifecta targeted LGBTQ youth in other ways as well this year. Before passing SF 496, they approved a school bathroom bill and a ban on gender-affirming care for transgender or nonbinary minors.)

New restrictions on “age-appropriate” content have made many books reflecting the experiences of LGBTQ youth inaccessible in school libraries. Some school-based Gender-Sexuality Alliances (GSAs) have stopped meeting or have dwindled as schools restricted staff involvement, or students stayed away for fear of being outed to their parents. Some LGBTQ students, including plaintiffs in this case, have been censoring themselves at school, to avoid getting peers or supportive teachers in trouble.

It’s hard to imagine how it would feel to have powerful politicians suggest the government needs to protect the “innocence” of your peers by discriminating against you in school, or denying people like you exist.

The state asserts the LGBTQ students have suffered “no injury in fact” due to SF 496. Plaintiffs’ belief that the law stigmatizes the LGBTQ community and seeks to erase it from schools amount to “catchy sound bites, not concrete, particularized injuries cognizable under the First Amendment.” They can’t claim the law promotes self-censorship, because

SF496 does not regulate their conduct. Nothing in that law prohibits students from “taking pride” in who they are, “being honest and open about” their identities, “wearing clothing that could identify” them as homosexual, or sharing their gender identity or sexual orientation with others, including teachers or staff.

Similarly, the state claims the plaintiffs can’t be harmed by the new restrictions on what teachers can say in class, because those provisions don’t apply to students. They also can’t be harmed by the “forced outing” provision, because their own parents are supportive. Plus, the law doesn’t mention GSAs or expressly limit their operation.

The state sums up by saying, “Plaintiffs do not face irreparable harm. Indeed, as described above, they face no harm at all—they are not covered by the law and it cannot be enforced against them.”

Other passages in the state’s brief imply the book bans amount to a minor inconvenience: “should Plaintiffs wish to access books that are removed from their school libraries, they have ample ability to do so from other libraries or booksellers—and the costs of doing so are quantifiable and compensable.”

The state response to the Penguin Random House lawsuit also denies any irreparable harm: “The authors are not chilled from publishing their books, which are readily available in libraries and bookstores. And the educators’ subjective fear of punishment is not a cognizable harm. It is incommensurate with the enforcement mechanism in the Library Program, which requires repeated knowing violations.”

Bleeding Heartland will return to these legal arguments after Judge Locher issues his decision.

Attorneys for the state did not speak to the media following the December 22 hearing, but attorneys for the plaintiffs were upbeat. Novack reminded reporters that plaintiffs in the Penguin Random House case already prevailed on one of their two “core claims,” since the state now acknowledges books depicting sexual orientation and gender identity are allowed in school libraries.

Novack continued, “On the remaining question, which is whether or not a book that happens to depict sex has value and therefore has to be recognized in its totality, we feel very confident the court will see it our way. That there must be a contextual analysis of the work, done by a qualified educator such as a librarian or teacher, before it is tossed out.”

Nathan Maxwell, senior attorney for Lambda Legal, told reporters at a virtual news conference, “We were extremely heartened to see just how prepared the judge was. He had clearly done his reading, and then some. And we’re very optimistic about our chances here.”

3 Comments

thanks for breaking this down

Hard to tell if the State hasn’t fully grasped the issues/contradictions around pronouns/gender and or of they are now aware but are indirectly rejecting attempts at reform by claiming neutrality of their position, however on the issue of the State taking a position by allowing (or not) certain books I agree with your source that this is “an incredibly extreme argument” but if the librarians (or whoever the “expert” is) is an employee/agent of the State then I don’t think that’s a contradictory position to take, as for what’s “absurd” or not see the Supreme Court on issues like guns rights and tell me if like “pornomgraphy” this is in the eye of the beholder on the bench or not…

dirkiniowacity Tue 26 Dec 10:22 AM

I really appreciate your work

I really appreciate your work on this, Laura. I’ve been sending your analyses of these lawsuits to our teachers’ union membership.

Steve Peterson Tue 26 Dec 1:41 PM

many thanks, Steve

These cases are so important. I’m committed to providing in-depth coverage as this litigation proceeds.

Laura Belin Tue 26 Dec 9:29 PM