Attorney General Tom Miller can remain on the Democratic primary ballot, the State Objection Panel affirmed on March 29, after determining his campaign had collected at least 77 valid signatures in eighteen counties, as required by Iowa law.

If he had been knocked off the ballot, Miller could have been nominated at the Iowa Democratic Party’s statewide convention in June. However, failing to qualify would have been an embarrassing misstep for a longtime office-holder.

Almost all of the legal arguments Miller’s representative advanced failed to convince a majority of the three panel members: Secretary of State Paul Pate, Lieutenant Governor Adam Gregg, and State Auditor Rob Sand. But one neat trick forced the two Republicans to accept enough Story County signatures for the campaign to cross the threshold.

SIGNATURES CHALLENGED IN FOUR COUNTIES

The attorney general is a member of the State Objection Panel, which hears challenges to Iowa candidacies every two years. But Miller rightly recused himself from considering this matter, which is why Gregg (who was the GOP nominee for attorney general in 2014) replaced him, just for this agenda item.

Alan Ostergren, an attorney who has worked for various Republican campaigns and committees, wrote the objection filed on behalf of Story County resident Teresa Garman and appeared before the panel to summarize the case and answer questions.

Here’s the full 59-page document, for those who want to dive in.

Miller’s campaign far surpassed the requirement that candidates for statewide offices collect 2,500 signatures on nominating petitions. His campaign appeared to meet the 77-signature threshold in 21 counties. The objection challenged signatures in four of them, which would have brought the campaign down to only seventeen counties—not enough to qualify for the ballot. According to the objection:

- The campaign fell short in Black Hawk County because of two duplicate signatures.

- It fell short in Mills County because one page omitted Miller’s county of residence near the top, rendering all 20 signatures on that petition invalid.

- Nine Story County signatures should not be counted for various reasons (the objection claims ten signatures are invalid, but goes on to challenge nine).

- The campaign missed the mark in Warren County mostly because of signatures from Simpson College students.

The panel spent nearly an hour and a half listening to Ostergren and Miller’s representative, Nick Klinefeldt, asking them questions, and deliberating over the challenged signatures. Iowa Starting Line live-streamed the hearing (video here), and I live-tweeted the discussion (starting here).

The big picture: Ostergren wanted the panel to interpret Iowa law more strictly, disqualifying individual signatures or petition pages for any mistake. Klinefeldt spoke about the panel’s “wonderful history,” using a standard of “substantial compliance” with state law and not rejecting signatures by “elevating form over substance.”

Ostergren noted that the legislature recently amended one part of Iowa Code to reduce the State Objection Panel’s discretion. Klinefeldt argued that didn’t change the “substantial compliance” standard. He suggested that a hyper-technical interpretation of the law might not even be constitutional, since the right to vote, and by extension the right to nominate one’s preferred candidate, was fundamental.

Things didn’t look promising for Miller as the panel discussed each county where signatures were questioned.

TWO COUNTIES EASILY KNOCKED OUT

The Miller campaign conceded Black Hawk County, where two of its 77 signatures were duplicates. (Note to candidates: never submit exactly the number of signatures you need in any context!)

Regarding Mills County, where one page failed to list Miller as a Polk County resident, all three on the panel agreed that the legislature limited their discretion when it added this sentence to Iowa Code in 2021: “Objections relating to incorrect or incomplete information for information that is required under section 43.14 or 43.18 shall be sustained.”

Section 43.14 relates to nomination papers. The mandatory information on petitions includes “a statement of the name of the county where the candidate resides.”

I would argue that for the 20 Mills County voters who signed a petition to place Tom Miller on the Democratic primary ballot as a candidate for attorney general, his county of residence is immaterial. He’s seeking a statewide office. I would consider such a petition to be substantially compliant with the legal requirements.

But Gregg said he was persuaded that with the recent change to Iowa Code, the panel had no discretion. The objection must be sustained. Pate and Sand agreed, putting the Miller campaign below the threshold in Mills County.

REPUBLICANS INCLINED TOWARD STRICT INTERPRETATIONS

Story County came next. Miller’s campaign started with 85 signatures. The panel agreed to reject a signature from someone who listed a Polk County address. There were two duplicate signatures. That’s three down.

Disagreements emerged as the panel discussed challenges based on Iowa State University dormitory addresses or incorrect dates.

Missing dorm room numbers

Iowa Code 43.15 requires voters signing nominating petitions to provide “the signer’s residence, with street and number, if any, and the date of signing.” It does not say the voter must provide a dorm room or apartment number. However, Ostergren sought to invalidate two signatures provided by students who listed an “Iowa State University residence hall” without any room number.

Sand argued that the dorm room number is immaterial and not required under the law. He noted the legislature could have amended the code to require such information but did not. The Secretary of State’s office also did not mention dorm room or apartment unit numbers in its guide for primary candidates.

Sand added that the State Objection Panel has always resolved ambiguity in favor of ballot access. The statute says you have to have street name and building number, and that you can’t use a post office box. But a university dorm is not a PO box under a fair reading of the statute.

In an ominous sign for Miller, Sand said he agreed with the objection related to Warren County, where six Simpson College students wrote down the student center address where they receive mail, rather than their residence halls. Those students don’t live in the student center, but the Iowa State students who signed in Story County do live in the dorms they wrote down.

With the Simpson College signatures out, Miller was guaranteed to fall short of 77 in Warren County. That meant it all would come down to Story County.

Gregg agreed with Ostergren, who said a signature can’t be counted if the voter provided only a partial address.

Sand read that to mean if someone didn’t list their street name, building number, and/or city of residence. Again, the legislature could have required an apartment or dorm room number but did not.

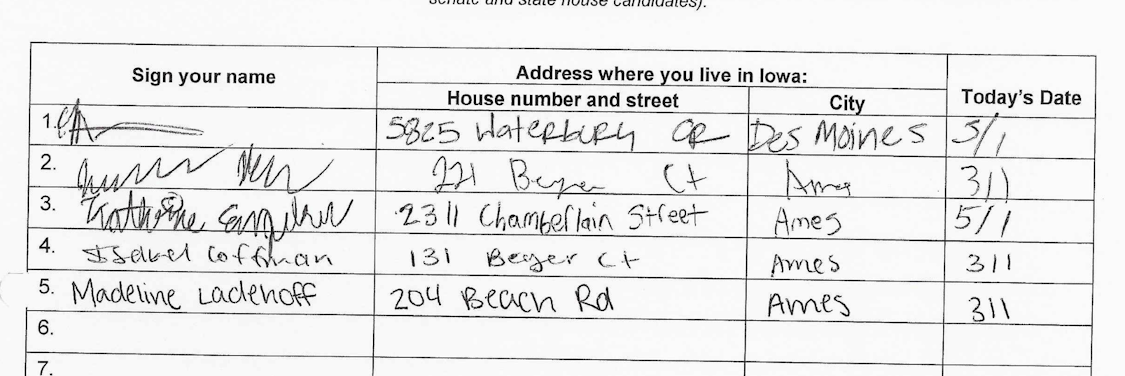

Pate asked, isn’t an apartment number required for registering to vote? And doesn’t the post office require such details? (Worth noting: the official petition form produced by the Secretary of State’s office asks for “House number and street” in the address section—not for dorm or apartment numbers.)

Gregg repeated that under the statute, the panel has to sustain an objection if the voter provided incomplete information. A partial address is not enough. He voted to sustain the objection to the two signatures with no dorm room numbers. Pate agreed: “The legislature has tried to tighten this up,” and “the Post Office does mean something to me.” The Republicans outvoted Sand.

Miller was now down to 80 signatures in Story County. Remember, he needed at least 77.

Incorrect date

One Story County voter had marked the date as “5/1” on a page when the rest of the signatures read “3/1.” Ostergren said it’s obvious the person didn’t sign on May 1, so the signature must be struck.

Sand recalled a 1988 decision by the State Objection Panel, the Dvorak case. It was on point: a signature was missing the date. Using the “substantial compliance” standard, the panel said you can look at the people who signed before and after to infer the missing date. (As Iowa’s attorney general, Miller was among the panel members who decided that case.)

Sand noted that the relevant portion of Iowa’s election law has not been amended since 1988. In this case, the context made clear that the voter signed on March 1 and meant to write “3/1,” like the others.

Klinefeldt said the Iowa standard has always been to consider whether something is material. People can use ditto marks rather than writing the actual date–that’s “readily discernible” (they meant the same date as the person who signed above). He speculated that if the statute were as “technical” as Ostergren urged, it would raise a constitutional issue.

Gregg countered: why bother with a date if it doesn’t have to be correct? Sand said Ostergren would be right if a bunch of voters signed the same page and put down no date. That would be invalid. He repeated that the State Objection Panel has long interpreted law to favor ballot access. We can see when these voters signed.

Pate characterized the situation as a “sticky wicket.”

Gregg made a motion to sustain the objection because the date was incorrect, not incomplete (as a signature had been in the 1988 Dvorak case). Sand argued for denying the objection. It’s the legal equivalent of a “scrivener’s error,” and courts have long inferred intent when that happens.

Pate voted to sustain the objection. The signature was out, and Miller’s campaign was down to 79 signatures in Story County.

THE ONE NEAT TRICK

The objection challenged two Story County signatures from voters who were registered in other counties. Ostergren said Iowa law doesn’t allow people to be registered in two places at once.

For Klinefeldt, this was an easy call: the code refers to “eligible” voters, not registered voters. These ISU students are eligible to vote in Story County for the June 7 primary, even if they previously registered elsewhere.

The Republicans on the panel had sided with Ostergren on every point raised so far. Now there was a problem.

While presenting Miller’s case earlier in the meeting, Klinefeldt had questioned Garman’s standing to bring this challenge. Iowa Code 43.24 says such objections “may be filed in writing by any person who would have the right to vote for the candidate for the office in question.” Voter registration records show Garman was a Republican at the time she filed the objection, and therefore unable to vote in an Iowa Democratic primary.

Ostergren responded that Iowa law allows voters to change their registration even on election day. So Garman is eligible to vote in the June 7 Democratic primary, if she wants to.

When the panel turned their attention to the Story County signers registered to vote in other counties, Sand said that to be consistent, we have to look at what voters can do, and we should decide in favor of inclusion. In other words, we can’t say those voters can’t sign Miller’s petition (even though they could change their registration address to Story County on or before June 7), but Garman has standing to object, since she can register as a Democrat in the coming weeks.

Molly Widen, legal counsel in the Secretary of State’s office, then brought up a precedent from 2004. When considering an objection related to incorrect addresses, not consistent with voter registration records, the State Objection Panel said many of those people had probably moved since they last cast a ballot. They concluded that the address on a nominating petition doesn’t have to be same as voter registration records.

Widen added that if these ISU students register to vote in Story County before the primary, it would revoke their registrations from other counties. Going back to the 2004 precedent: having a different address on voter registration records did not invalidate a petition signature.

Sand pointed out that in the 2004 decision, the panel said state law should be “liberally construed” to allow ballot access.

Gregg didn’t sound convinced. But the Republicans were in a bind. Disqualifying those two Story County signatures might force them to reject Garman’s objection entirely.

The panel unanimously agreed not to strike those two signatures.

THE ENDGAME

Moments later, all three panelists agreed to reject a signature by someone who listed a Dallas County address. That brought Miller down to 78 in Story County.

A few minutes after that, they sustained the objection to the Warren County signatures, mostly related to the Simpson College issue. Despite Klinefeldt’s argument (which sounded convincing to me), the panel determined that the student center is comparable to a post office box and doesn’t prove those college students live on campus. Sand mentioned that you need to know a student’s residence hall, but not the unit number, to confirm their address.

So Warren County was out. But it didn’t matter: Miller was just over the line in Story County, giving him exactly the eighteen counties he needed to qualify for the ballot. “All’s well that ends well,” the attorney general told reporters while the panel took a short break after the deliberations.

Those two Story signatures by voters registered elsewhere made the difference between Miller remaining on the primary ballot and having to do a workaround at Iowa Democrats’ state convention.

And those two Story signatures might not have survived, if Ostergren had thought to advise Garman to become a Democrat before signing the objection he drafted.

Top photo: Attorney General Tom Miller (right) watches as the State Objection Panel considers a challenge to his nominating papers on March 29.

1 Comment

I really hope future Democratic candidates will learn lessons from this year...

…because signature lists should have adequate numbers of valid signatures, plus extra signatures just in case. Signature lists should not result in challenge stories that read like THE PERILS OF PAULINE.

PrairieFan Thu 31 Mar 12:44 PM