Tax and budget policy expert Randy Bauer explores the likely impact of a court ruling that will allow states to collect more sales tax from online purchases. Iowa Republicans were counting on that authority, having approved expanded sales tax collections as part of the tax bill enacted in May. -promoted by desmoinesdem

Years ago, I did a tongue-in-cheek summary of major tax issues and used variations on movie titles as lead-ins to discussions of various taxes. At that time, I lamented the various factors eroding state and local government sales tax collections (and recently reprised these concerns on Bleeding Heartland), labeling the discussion “Dearth of a Sales Tax.” With that background in mind, it’s time to cue up Star Wars theme music for this year’s summer tax blockbuster, The (Sales Tax) Force Awakens.

On June 21, 2018, the U.S. Supreme Court (SCOTUS) threw sales tax dependent state and local governments something of a lifeline, as it overturned two long-standing sales tax precedents that had limited the ability of governments to compel the collection of sales taxes from sellers without a physical presence in their state.

In South Dakota v. Wayfair (Wayfair), the SCOTUS overturned prior case law dealing with catalogue and phone sales (National Bellas Hess v. Illinois Department of Revenue, 386 U.S. 753, 1967) and Internet sales (Quill v. North Dakota, 504 U.S. 298, 1992) and ruled that states (and, by extension, local governments) have the ability to compel (at least some) sellers without a physical presence to collect and remit sales tax from customers.

This is a significant achievement in the ongoing fight to collect this tax. As noted in my prior piece for Bleeding Heartland, sales tax collections, as a share of personal income, have been declining for decades for multiple reasons. For many governments, the only way to prevent a significant revenue decline for what is generally a key revenue source has been to continually increase the sales tax rate, but this approach is problematic. First, as the rate increases, the tax becomes more regressive (because lower income households devote more of their income to sales taxable goods and services). As the tax rate rises, it also has more impact on market decisions – both for producers and consumers. Finally, it can also create “border effects” where differences in sales tax rates drive consumer purchasing decisions that may not otherwise align with market decisions.

While Wayfair is welcome relief for sales tax dependent governments, a review of the facts leading up to the decision and the decision itself suggests that this is not a clear “slam dunk” victory for the ability of governments to compel collection of sales tax from all phone/catalogue/Internet sellers. The following will discuss what this means for governments, sellers and consumers in this “brave new world” of sales tax collection.

TAX BACKGROUND

Sales tax dependent governments have been dealing with the fallout from the rulings in Bellas Hess and Quill for decades. As the “Amazon generation” of consumers spent a greater share of their dollars online, states began looking for ways to stem this revenue loss.

The Streamlined Sales Tax Agreement (SSTA) was initiated by the National Governors Association (NGA) and the National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL) in 1999 in response to the Bellas Hess and Quill court decisions. The goal was to increase uniformity that would either lead to greater vendor voluntary collection or the reconsideration of the two Supreme Court decisions.

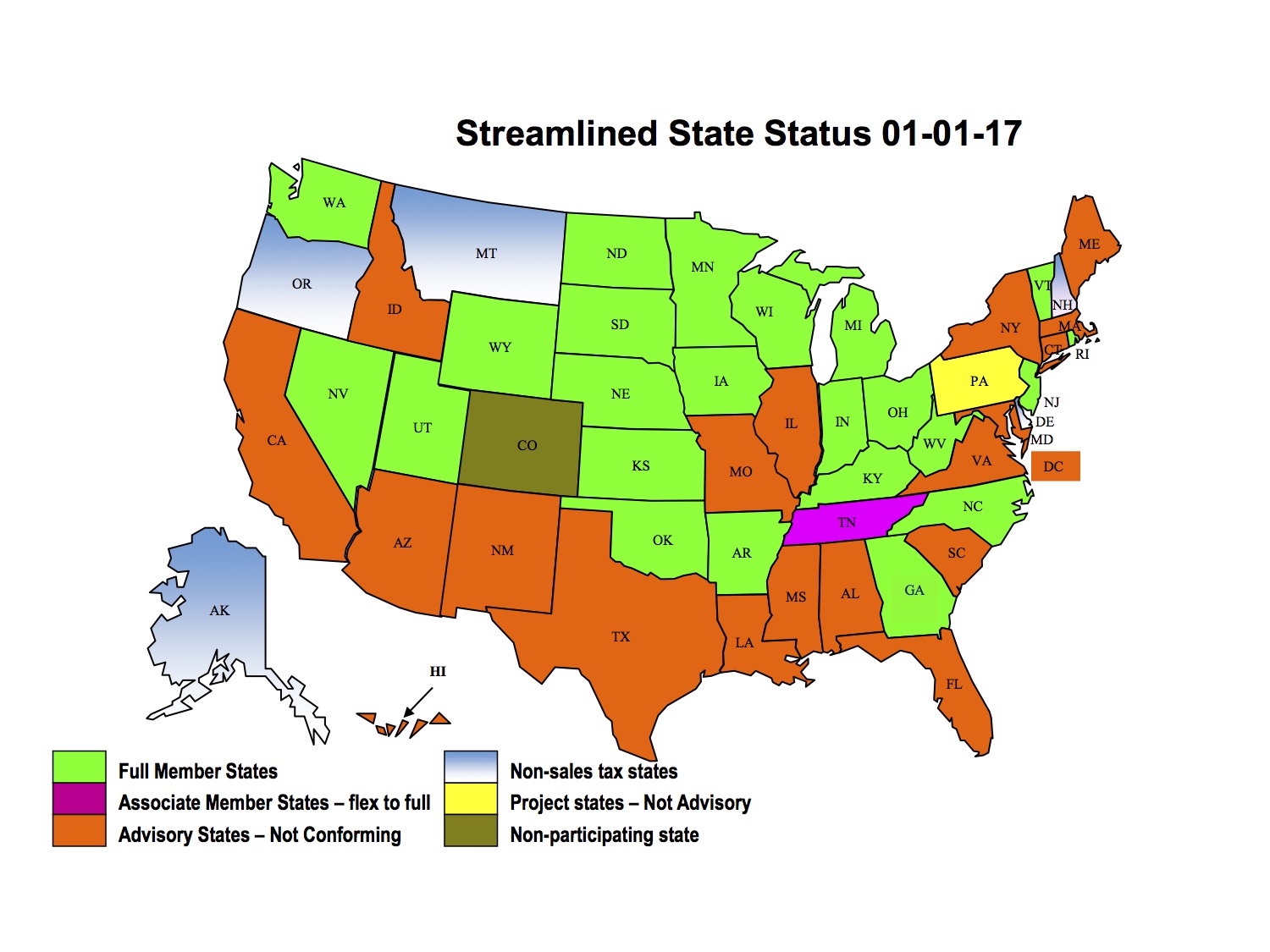

As of 2017, 24 states participate in the program as full members (as shown in the following figure). While this is a significant number, several major states do not take part (notably California, New York and Texas), which limits the agreement’s impact.

SSTA State Participation Status (as of January 1, 2017) Source: Streamlined Sales Tax Governing Board

The SSTA is beneficial to states because it minimizes costs and administrative burdens on retailers that collect sales tax, particularly retailers operating in multiple states. In turn, this leads to voluntary collection of the tax by participating sellers. As an example, the State of Arkansas reported that it has collected approximately $107 million through the SSTA through the end of 2017. Conversely, the SSTA limits some state flexibility related to definitions and the treatment of sales taxes.

While the SSTA has led to some voluntary collection of sales tax by out-of-state vendors without nexus, it has failed to achieve the “critical mass” of state participation necessary to “move the needle” on either voluntary collection or federal action. Given the lack of participation by several major states, it is likely that it will never be the vehicle to be a primary remedy for the revenue loss from the Quill decision. It is notable, however, that participation in the SSTA was cited as a positive in the weighing of the impact of the South Dakota law on interstate commerce in the Wayfair decision.

Opponents of the Quill decision have also sought action by Congress – after all, both Bellas Hess and Quill were decided on commerce clause issues, and Congress has the constitutional authority to regulate interstate commerce. Various forms of what is generally known as the Marketplace Fairness Act (MFA) have been introduced in Congress since 2011 (including in the current Congressional session). To date, none has made it to the president’s desk; the closest it has come to passage was in 2013, when it passed the Senate but was not considered in the House. That version of the MFA would have authorized every SSTA state to require all sellers not qualifying for a small-seller exception (annual gross receipts in total U.S. remote sales not exceeding $1 million) to collect and remit sales and use taxes with respect to remote sales under provisions of the agreement, but only if the agreement includes minimum simplification requirements relating to the administration of the tax, audits, and streamlined filing.

The Congressional action (or lack thereof) to date on the MFA has been a point on contention on both sides of this debate. Those who support the Quill standard argue that Congress has the authority to act, and their decision to not do so suggests their comfort with the existing standard. On the other hand, supporters of the MFA point out that its Senate sponsors for the current version of the bill are a bipartisan group making up more than half of the Senate, while the House has never taken a full floor vote on the bill.

Given this federal inaction, states have developed creative legislative approaches toward requiring (directly or indirectly) that e-commerce sellers collect sales tax on their behalf. A lot of early efforts were directed at Amazon, which is recognized as the predominant seller in the Internet marketplace. These efforts began in New York in 2008, in what is often referred to as the “Amazon tax.” Under the New York State statute, a rebuttable presumption is created that a nonresident Internet seller has nexus with the State for sales/use tax purposes if (i) the nonresident has agreements with in-state companies whereby potential customers are referred to the nonresident, and (ii) the nonresident’s gross receipts from customers under such an agreement exceed $10,000 during the previous four quarters.

Since that first state foray – and the litigation that followed – other states have also considered and/or adopted similar legislation. It could be argued that the multiple state efforts to create “Amazon nexus” has proven successful, as Amazon is (as of April 1, 2017) collecting sales tax on sales in all 50 states (although this does not necessarily apply to its market partners). An alternate point of view is that Amazon has begun to emphasize speed of delivery, which requires warehouses and/or storage facilities in most states anyway.

Besides these “marketplace sellers” (Amazon taxes), additional attempts have focused on creating what is referred to as “economic nexus” (where the amount of sales in dollars or number of transactions into a state creates sufficient grounds to require collection of the tax) have become popular, with many states enacting this type of statute. This is the basis of the South Dakota and Alabama statutes, which are seen as the first forays into this definition of nexus. Key state policymakers in both South Dakota and Alabama have suggested that the primary focus of their state statutes was to put a test case in front of the SCOTUS for possible reconsideration of Quill.

As examples several states passed economic nexus standards during 2017:

• Wyoming, North Dakota, Indiana, and Maine (March-April-May-June) each began imposing standards on sellers with $100,000+ in sales or over 200 separate transactions.

• Ohio (June) determined that “substantial nexus” exists if the seller has gross receipts in excess of $500,000 and if the seller uses in-state software to sell tangible personal property or services or enters into an agreement with another person to accelerate or enhance the delivery of the seller’s website to others.

• Similarly, Rhode Island (August) enacted provisions requiring any non-collecting retailer with in-state sales of $100,000 or more or engaged in 200 or more transactions with in-state customers to register for a sales tax permit and begin collecting and remitting sales tax or comply with detailed notice and reporting requirements. The bill defines a “non-collecting retailer” as any person meeting certain criteria, including using in-state software to make sales of tangible personal property or taxable goods or services.

• A Tennessee administrative rule provides that out-of-state dealers that engage in the regular or systematic solicitation of consumers in Tennessee through any means and make sales that exceed $500,000 to consumers in the state during the previous 12 months have substantial nexus with Tennessee.

As a useful point of comparison, the South Dakota economic nexus law, which was at the heart of the case SCOTUS decided last month, establishes economic nexus if a seller, on an annual basis, delivers more than $100,000 of goods or services into the state or engages in 200 or more separate transactions for delivery of goods or services into the State.

Additionally, several states passed marketplace sellers standards:

• Minnesota expanded the definition of a “retailer maintaining a place of business in the state” to include having a representative such as a “marketplace provider” with sales over $10,000 into the state.

• Washington now requires agents with sales of $10,000 and referrers with a physical presence in Washington or at least $267,000 in sales into state are required to either collect sales/use tax on sales to Washington consumers or follow the use tax notice and reporting requirements.

The state of Colorado adopted a different strategy, requiring retailers to either collect the tax or face significant paperwork requirements. The Colorado law survived court challenges, including the U.S. Supreme Court declining to review it after the U.S. Court of Appeals found it constitutional (a case where then-Appeals Court Judge Neil Gorsuch ruled in the favor of the state. Under that law, retailers that do not collect sales taxes must file a report with the State Department of Revenue on how much their Colorado customers have purchased and must inform customers that they may owe state taxes on the purchases. The law also requires large online retailers to send customers a notice every time they buy something to explain that they may owe use tax. If the customer makes more than $500 a year in purchases, the retailer must also send them an annual summary of their purchases. Finally, the seller must file an annual report with the state detailing customer name, billing and shipping addresses and the total amount spent each year.

This approach became something of a national model as an alternative to the economic nexus approach. Those who advocate for it believe it will inform consumers of their obligation to pay use tax on their out-of-state purchases or lead to sellers voluntarily collecting the tax to escape the reporting requirements (for them and their customers). States who have recently adopted Colorado-type reporting standards include:

• Alabama gives the Department of Revenue the authority to require non-collecting vendors to notify Alabama customers of use tax obligations.

• In Louisiana, out-of-state vendors with sales greater than $50,000 annually must inform Louisiana customers at the time of the transaction that the sale is subject to use tax. Vendors must also provide an annual statement to their customers indicating the total purchases for the year. An annual report must be sent to the Louisiana Department of Revenue in addition to customer notification.

Interestingly, Rhode Island allows the vendor to choose between collection (via their economic nexus statute detailed above) or via Colorado-like reporting requirements.

Finally, Iowa deserves mention as an example of a “belt and suspenders” approach to tax collection. Iowa has expanded its definition of sales tax nexus to include economic nexus (based on sales of more than $10,000 in the prior calendar year into the State), the “Amazon Tax” nexus, and, if those don’t hold up to judicial review, a Colorado-style reporting requirement.

Iowa relied on broadened sales tax collections as one method to reduce other tax rates. According to estimates by the Legislative Services Agency, changes in sales tax collection would increase revenue collections by $66.4 million in FY 2020. At the same time, Iowa also expanded its definition of services subject to tax, primarily by including digital goods, which was estimated to increase sales tax revenue by $26.2 million in FY 2020.

THE SUPREME COURT LEAD-UP

When the SCOTUS agreed to hear the Wayfair case, various tax prognosticators suggested there was a strong possibility the Court would alter the Quill precedent. This was largely based on a couple of factors:

1. Justice Anthony Kennedy, often considered a key swing vote on the Court, had opined in a 2015 case on the need to re-examine Quill, writing (in a concurring opinion) that there was a powerful case to be made that a remote seller doing extensive business within a State has a sufficiently substantial nexus to justify some minor tax collection duty, even if that business is done through mail or the Internet.

2. Justice Gorsuch, as previously noted, had served on the U.S. Court of Appeals Tenth Circuit three-judge panel that upheld the constitutionality of Colorado’s reporting requirements law (previously discussed). In that case, Gorsuch’s concurring opinion noted that the physical presence requirement of Quill may have “a sort of expiration date.” It is also notable that, at the beginning of his legal career, Gorsuch clerked for Justice Kennedy.

The other factor that tended to suggest a change is the fact that the SCOTUS did not have to take the case if it was inclined to maintain the status quo – as the Quill precedent was relied upon by the South Dakota Supreme Court in ruling in favor of Wayfair.

For those reasons, the general belief was that some change in Quill would come out of the SCOTUS decision. As an example, in an analysis of each of the SCOTUS justices’ rulings/judicial philosophy, the Tax Foundation suggested that the likely outcome of the case would be in favor of South Dakota, on a 5-4 decision, with possibly two other justices ‘in play.’

I will admit to having a similar pre-disposition. In a study I led for the Long Island (New York) Regional Planning Council on alternatives to the property tax, we estimated additional local sales tax collections of $92 million in FY2020 based on likely action by the SCOTUS in the Wayfair case.

However, the oral arguments and subsequent questioning by the Supreme Court Justices suggested significant concerns with upholding the South Dakota law, particularly related to the negative impact on small businesses. After oral arguments, there was a distinct shift in the opinion of many tax experts – with many (maybe even a majority) believing the Quill precedent would be upheld. In fact, a prominent fantasy league devoted to Supreme Court predictions (LexPredict Fantasy SCOTUS) predicted five justices to affirm (and maintain Quill) and four to reject. Interestingly, in the 5-4 decision, the one justice that the fantasy league consensus got wrong was Samuel Alito – all of the other eight Justices voted as the consensus projected.

THE SUPREME COURT DECISION

SCOTUS upheld the South Dakota law and remanded the case in a 5-4 decision. As was expected, Justice Kennedy wrote the opinion for the Court. He was joined by Justices Clarence Thomas, Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Alito, and Gorsuch. Thomas and Gorsuch filed concurring opinions. Chief Justice John Roberts filed a dissenting opinion, joined by Justices Stephen Breyer, Sonia Sotomayor, and Elena Kagan.

Kennedy’s decision was a sweeping indictment of the prior decisions in Bellas Hess and Quill. He wrote that “Quill is flawed on its own terms” and noted that “the Quill Court itself acknowledged that the physical presence rule is ‘artificial at its edges.’”

The decision relied greatly on changes to the economy since the past rulings, finding that “Modern e-commerce does not align analytically with a test that relies on the sort of physical presence defined in Quill.” In this respect, Kennedy notes that the rapid rise of e-commerce outweighs past precedent, referring to past SCOTUS language that “stare decisis is not an inexorable command.” Referring to his own concurring opinion from 2015, Kennedy notes that “Though Quill was wrong on its own terms when it was decided in 1992, since then the Internet revolution has made its earlier error all the more egregious and harmful.”

On the issue of concern during oral arguments – impact on small businesses – Kennedy underscored the value of several aspects of the South Dakota statute, including:

• The small seller exception, based on dollar amount or number of transactions;

• Not retroactive

• State is a party to the Streamlined Sales and Use Tax Agreement, which requires single, state-level tax administration, uniform definition of products and services, simplified rate structures and other uniform rules.

Based on those factors, the opinion determined that the South Dakota statute is not an unconstitutional infringement on interstate commerce. This weighing is important, as it suggests that states are not given “blank check” authority to compel collection of sales taxes from remote sellers. In fact, it is possible that states with a lower threshold for collection purposes (such as Iowa’s $10,000 a year in sales threshold) might wish to reconsider and pass the “SCOTUS approved” South Dakota version of economic nexus.

THE IMPACT

The estimates of lost state and local government revenue from the Bellas Hess and Quill decisions vary considerably, but all agree the amounts in the aggregate run into the billions of dollars. One study, conducted by the State of Washington that is often quoted by the National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL) puts the combined loss from these two court cases at $26 billion in 2015. Of course, some developments since that time (primarily Amazon’s voluntary collections in all 50 states) may have reduced this estimate – but continued growth in e-commerce may have increased it. It is quite possible that the two issues are something of a wash. For a different perspective, the Government Accountability Office projected that states could collect an additional $8 to $13 billion annually in sales tax, which amounts to a 2 to 4 percent increase in revenue.

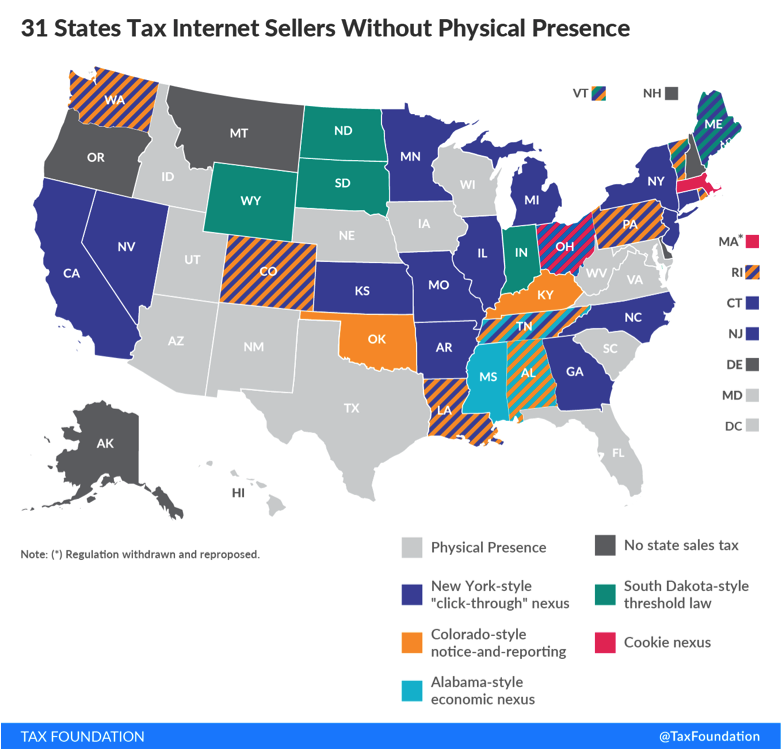

The issue now lands in the laps of primarily state (and some local) governments. Exactly who is now subject to collecting the tax will vary from state to state, depending on that state’s statutes (or lack thereof). According to the Tax Foundation, 31 states have some form (or forms) of requirements for the collection of sales tax by remote sellers. By the way, I disagree with their characterization that this is a tax on internet sellers. Rather, it is a requirement to collect the tax from buyers. But it’s their graphic:

THE AFTERMATH

Last month, I referred to the SCOTUS ruling in Wayfair as a “full employment for state revenue departments decision.” I stand by that assessment. In many states, there will be an immediate need for a review of state statutes (to determine whether there is substantial compliance with the SCOTUS opinion), writing of administrative rules, contacting/educating remote sellers for compliance purposes, estimating revenue gains and/or writing new legislation and working with legislators on its passage. All of the above will require substantial time and effort.

In addition to those up-front tasks, there will also be concern about ongoing compliance. State revenue departments likely will want to devote additional time and resources to sales tax audits, although that will require a case-by-case weighing of potential costs and benefits.

Besides revenue departments, the decision is likely to be a boon to at least a couple of other stakeholders. One may be the Streamlined Sales Tax Agreement. Because the SCOTUS opinion notes that part of the weighing of impact on sellers related to interstate commerce was South Dakota’s participation in that Agreement, it may lead non-participating states to rethink their approach. In turn, that could lead to more uniform sales tax treatment around the country – which would be a good thing.

Another group of stakeholders who are appreciating the decision are those companies who have made it their business to assist retailers with their sales tax collection responsibilities. There are literally thousands of state and local governments with sales taxing authority, and this also means thousands of varying sales tax rates, definitions of taxable goods and services and other regulations. In recent years, a variety of vendors have developed applications and methods that automate the sales tax determination and collect process. These businesses are likely to see a significant upturn in their corporate revenues as sellers scramble to comply with the various regulations after the SCOTUS ruling. One such company is Avalara – which recently went public. After the ruling, shares in that tax management firm rose as much as 32 percent, which extended gains that more than doubled its share price since it went public about a week before the decision was announced.

THE LAST WORD–FOR NOW

One issue that was raised in many discussions of the outcome of this case was whether it might finally compel Congress to act. Given the ruling, I doubt it. First, Congress is clearly divided on the issue – finding a middle ground that is substantially different from the SCOTUS ruling would be difficult. Also, given the deep pockets and strong lobbies on both sides, my guess is that most members of Congress will be happy to let this issue go and rely on the SCOTUS decision to guide taxing authority. That said, if there is a belief that many states eventually “overreach” in their laws applied to economic nexus, Congress might act.

I also wouldn’t be surprised if additional cases come before the SCOTUS seeking to put a finer point on what is or isn’t acceptable in state law related to interstate commerce. If that is the case, I expect that the SCOTUS will be more likely to narrow – rather than expand – state powers.

While this ruling has important revenue and other implications for states, keep in mind that the immediate revenue gains will be relatively small. It is also possible that some states (like Iowa) will use the additional revenue as an offset against other tax cuts – and income tax cuts are the order of the day in many states. It is also possible that some states will choose not to compel sales tax collection by remote sellers – and tell their constituents they “held the line on tax increases” (never mind that the use tax obligation exists regardless of how the collection of it is treated).

In the end, a number of economic, demographic and political issues are still eroding the sales tax base. While this is a victory for state and local governments on tax collections, the battle is far from over.

Randall Bauer is a director in the Management and Budget Consulting practice for the PFM Group. Since 2005, he has led its state and local government tax policy practice. He has numbered nearly half the state and many large local governments among his clients. Prior to joining PFM, he spent 18 years in state government, including serving for seven years as Governor Tom Vilsack’s State Budget Director.