James Larew presents a contrarian view on last week’s Democratic debates. -promoted by Laura Belin

When the smoke had cleared from the Battle of Gettysburg, fought from July 1 to 3, 1863, it appeared to have been just one more bloody battle in the midst of a war that had no obvious end in sight. Only later—after thousands more skirmishes had been fought—would it become clear that so much more had been achieved at Gettysburg. History would show that the Civil War’s end, culminating in General Lee’s surrender to General Grant, at Appomattox Courthouse, Virginia, on April 9, 1865 had been predicated nearly two years earlier, when the tides of the entire war had shifted in the Union’s favor at Gettysburg.

So, too, history may record that, on July 30 and 31, 2019, in Detroit, Michigan, well before Iowa’s 2020 presidential nominating caucuses had even been convened, two successive Democratic party presidential nominee debates involving twenty candidates significantly winnowed the field and defined the ultimate outcome of the nomination process: that former Vice President Joe Biden would be the party’s nominee.

Just as victorious Union generals had not directed a flawless battle plan at Gettysburg, neither had Biden’s Detroit performance been perfect. But, victories in war or in politics seldom require perfection; they require some combination of skill, perseverance and luck. By those measures, it may be declared, Biden won both Detroit debates—even the first one, at which he was not present.

Those victories solidly affirmed Biden’s candidacy in its leading position, one that will be very difficult, if not impossible, for his competitors to overcome before the Iowa caucuses. And, by that result, history may show that in the 2020 campaign, the Detroit debates displaced the importance of Iowa’s traditional political proving ground for presidential nominations.

How can it be said that Biden was the winner of the first night’s Detroit debate when he wasn’t even on the stage? Because he was there by proxy, represented, in effect, by other candidates who, perhaps unintentionally, without even mentioning Biden’s name, strengthened his position as the leading Democratic candidate, in at least two separate dimensions.

First, Biden’s own political moderatism was fortified, in absentia, by several lower-tier, least-viable moderates on the stage. As Abraham Lincoln once summarized, “Public sentiment is everything. With public sentiment, nothing can fail. Without it, nothing can succeed.” More than 150 years later, still, America’s general elections are won in the middle, and not at the ideological edges, of our political spectrum.

Seizing what they may have perceived to have been their last remaining moments in the national political sun, several of the more conservative candidates in the field—John Delaney, for example, but, others, too–launched reasonably well-aimed, unsettling rhetorical missiles at Bernie Sanders and Elizabeth Warren by, in effect, asking:

Sanders’ and Warren’s thought-provoking, well-stated answers to those types of questions, in turn, revealed positions, unapologetically embraced by each of them that, many argue, are not in-sync with the views of the large numbers of voters who occupy the volatile Great Middle of the electorate. Ballots cast from that region, however, frequently determine the outcomes of our general elections.

Unsettling political questions such as these—aimed by others at Biden’s principal rivals in his absence—allowed his more moderate candidacy to advance, without requiring him to assume confrontational stances that might have otherwise alienated voters.

On a second dimension at the first Detroit debate, Biden’s interests, again, in his absence, were advanced by others, even if inadvertently. Seemingly out-of-nowhere, little-known candidate Marianne Williamson’s eloquent, soliloquies created the impression that the candidate field was dominated more by policy wonks than by suffering-wizened-souls.

The collective memory recalls, however, that it is often those candidates who have genuinely suffered—and who have overcome—life’s most difficult struggles who, in response, are best able to connect genuinely with the most volatile members of our electorate.

Williamson is often characterized as too far “out there” to have any chance of winning the nomination. That may be true. But, on that first night of the Detroit debates, she presented compact, moving, spiritually-based critiques of the American political culture. Voiced from the farthest edge of the stage, Williamson reminded viewers of the central importance of political soul. By comparison, in a forum that had compressed too many bodies into too small a stage, her peers seemed one-dimensional.

Competitors may quarrel with Biden’s policy history or critique his rhetorical gaffes, but no one can deny that, in his lifetime, he has overcome astonishing human suffering. He has survived politically for many years, in a rough and increasingly-corrupt political era, with his dignity intact. And, even his most severe critics must concede that when Biden is “on”–channeling his soul-wizened past to his hopes for our collective future–he powerfully connects to citizens who, in the era of Trump, above all other yearnings, seek compassionate authenticity. Williamson carved out a void on the stage that Biden, even in absentia, could fill best of all candidates.

How can it be said that Biden was the winner of the second night’s Detroit debate when he sometimes appeared to lose track of where he was, rhetorically, in the middle of orchestrated sound bites, and when he had been subjected to sharp attacks from so many directions?

As so often happens on battlefields, here, too, Biden’s winning margin was not absolute, it was relative. The comparison, on that night, was not against Trump (whom he would substantially beat in a general election, public opinion polls reveal), but rather, against myriad candidates, a number of whom seemed poised to vanquish the former vice president on the Detroit’s Fox Theatre stage.

For one, the prognosticators had forewarned that Kamala Harris’s devastating attack upon Biden in the first round of debates a month earlier in Miami could lead to a knock-out punch in Detroit. But in fact, before she had that second chance to take a swing at Biden, Harris was unexpectedly silenced by Tulsi Gabbard’s brutal attack from her left flank.

Biden needed only to watch the political blood spill from the nearby podium; there would be no Harris-Biden rematch that night. So, in comparison to Harris, who had been dubbed as Biden’s most competitive debating peer, Biden had survived, without striking his own blow.

Biden’s winning difference on the second night included another critical dimension–recall the Williamson Soul Imperative. The former vice president created the most empathetic moment of all candidates that night. In the midst of his initially-floundering response to Kirsten Gillibrand’s odd harangue about a 1981 op-ed that he had apparently authored about eligibility for federal child care income tax credits, Biden, sharpened his focus and, speaking from the heart, reminded Gillibrand—and, all others–that he knows something of parental suffering and responsibilities.

Few persons in public life have been challenged as severely in private life as has been Biden. When, for example, as he explained to Gillibrand, after his first wife’s tragic death, he had fulfilled the role as a single father raising his young children, alone: juggling child care responsibilities while also managing the duties of high political office. The exchange with Gillibrand was Biden’s bookend moment to Williamson’s soulful remarks the night before. No candidate in the course of the second night’s debate had anything comparable to offer.

So, if it is true that Biden won both nights of debate in Detroit, it will then likely follow that his public opinion poll lead will increase in the days and weeks ahead. The order of candidates below him, within respective tiers (top, middle and bottom), may shuffle a bit, perhaps, but the shuffling will not affect his dominance over the field.

Does that mean that the race for the Democratic Party’s presidential nomination is over, even before it began? Not necessarily—any more than the Union victory at Gettysburg assured General Lee’s surrender at Appomattox Court House nearly two years later. By analogy, even if the tides have shifted in Biden’s favor, there are still many battles ahead—large and small—in the presidential nominating process. The Iowa caucuses pose daunting organizational challenges to front-runners and distant-finishers, alike. Biden will need to be an active participant in all of these facets if the advances achieved at Detroit are to be leveraged into a final nomination victory.

Yet, later, when viewed historically, lines of causality will be drawn. Time will tell, with respect to Biden’s candidacy, if such a line directly connected the July 2019 Detroit debates to the July 2020 Democratic national convention in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and finally, to the presidency in Washington, D.C. If so, some may conclude, retroactively, that, in 2020, the traditionally-critical importance of the Iowa caucus proving ground had been diminished, if not entirely bypassed, by the earlier showdown in Detroit.

If history supports such a course of events, it will not be because Biden was a perfect, gaffe-free candidate with a flawless policy history. Rather, it will happen because in Detroit, both as a result of planned and unplanned moments, ones combining an alchemy of skill, perseverance and luck, Biden’s candidacy was framed. From there, Middle America’s swing voters clearly identified Biden as a moderate and authentically compassionate candidate, one whose past experiences and street-knuckle credentials were viewed as the best possible match, in a perilous time, for a frightening alternative: the re-election of Donald J. Trump.

James C. Larew is an attorney in Iowa City. He served as general counsel and chief of staff for former Governor Chet Culver, a Democrat.

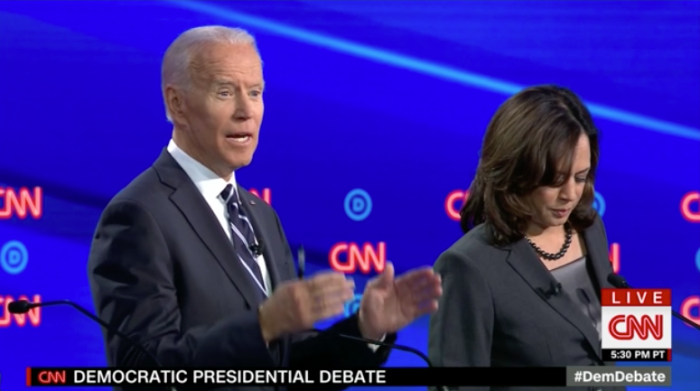

Top image: Screen shot from a CNN video of the July 31 debate in Detroit.

Editor’s note: Bleeding Heartland welcomes guest posts related to the Iowa caucuses, including analysis of multi-candidate forums or debates. Please read these guidelines and contact Laura Belin if you are interested in writing.

1 Comment

Not the right candidate, not the right time.

Biden is not campaigning very much.

When he does campaign, he looks tired, and does not take questions.

He often sounds confused, like my elderly mother. He speaks in seeming non sequiturs, until you fill in the blanks on your own and piece together what he meant.

Instead of talking about our vision for the future, a campaign with Biden at the head is one where all of us will have to do the work of explaining what he meant when he said…researching votes from 1986 in the process.

Democrats of Iowa, is this really the head of the ticket who will help us defeat Joni Ernst, elect four Democratic congesspeople, and help us win back the Iowa legislature?

EmilyatActivate Tue 6 Aug 9:14 PM