Dr. Glenn Hurst: The nursing homes know that if they accept one COVID-19 patient in their facility, they will likely be sending ten new patients to either the hospital or the coroner. -promoted by Laura Belin

As we look to reopen the U.S. economy, many questions arise regarding whose interests the economy serves. In the health care sector, the answer is large health systems, often at the expense of some of the most vulnerable populations in our state. Their vertical integration of the profitable components of health care provision, hospitals, surgery centers, rehab and physicians, and the casting off of components such as nursing care and hospice have acutely left the older generation at grave risk.

Today’s crisis illustrates the problem. The continued outbreak of novel coronavirus (COVID-19) cases in Iowa nursing homes should be shocking. The response to calls for assistance to protect these patients should be met with the same distress.

In western Iowa, we have watched in the shadow of Omaha, Nebraska’s outbreak and the devastation of the Douglas County Health Center, wondering, “When will it happen here?” As facilities across Iowa demonstrate the same or worse fate, other long-term care providers brace for what seems inevitable: the death and debilitation of the patients in their charge.

The evidence from around the nation and here at home should make it clear: no patient with COVID-19 should be kept in a nursing or assisted living facility with other high-risk individuals. Even isolation of patients within these facilities does not appear to work.

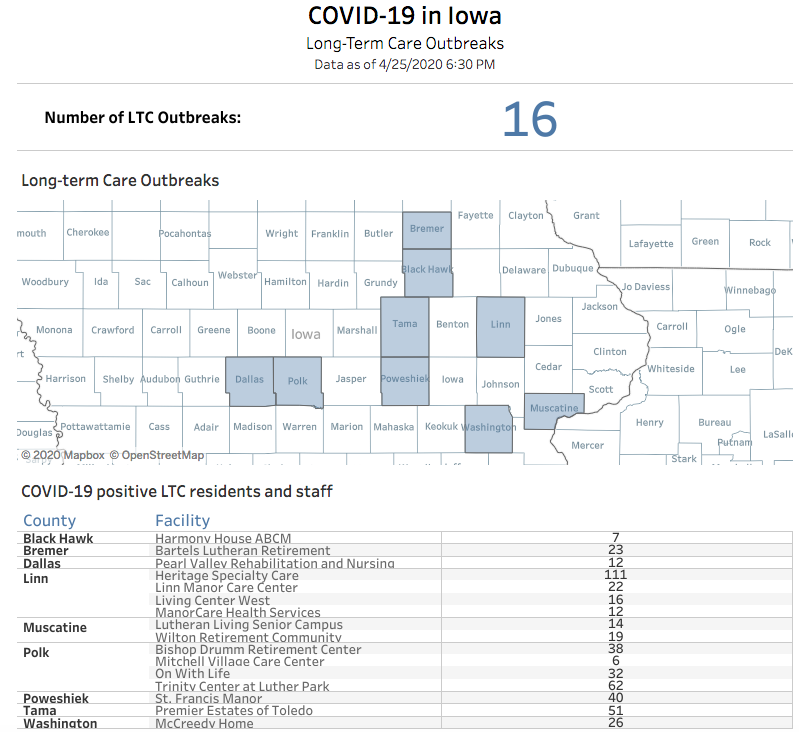

The numbers of cases in Iowa’s sixteen long-term facilities with reported outbreaks continues to grow daily. The latest available figures from the “LTC Dashboard” tab:

There is no way to know whether any facilities in the state are successfully containing these cases. When asked, the Iowa Department of Public Health declined to share the number of facilities that are limiting the spread in their homes. The suspicion is that there are very few. The state agency has also offered no new guidance since late March based on what successful facilities may be doing right.

At most Iowa nursing homes, defenses have been put in place to prevent any outsider from bringing the condition into the facilities. Administrators and staff should be congratulated for the Herculean efforts they have made to screen every person who comes through the door. They have devoted already strained resources to providing isolation and preparing their already limited staff for the single purpose of caring for any possible case.

These facilities are facing an unexpected challenge within the health care system. As hospitals look for places to send patients after they have begun to recover from their hospital admission, they are looking to their previous partner, the nursing home. As the data in Iowa shows, this is a short-sighted vision with regards to COVID-19.

When nursing home patients account for 10 percent of hospital COVID-19 admissions and 50 percent of deaths attributed to the virus, the current plan is clearly failing this population. All available evidence suggests that if a contagious patient is admitted to the nursing home, spread will occur, and the consequences will be dire.

But large health systems appear to see the problem from only one perspective: the need to empty their beds for the next patient. They have been struggling to grasp the responsibility they hold by sending that patient along the traditional path to a nursing home. In so doing, they will assuredly increase the need for more hospital beds by placing a disease carrier in the midst of the highest risk population.

The nursing homes know that if they accept one COVID-19 patient in their facility, they will likely be sending ten new patients to either the hospital or the coroner. Our facilities live in fear of the day that Iowa’s government follows the reckless behavior of other states and orders the nursing homes to accept these patients.

While battling to protect their patients from inappropriate admission, nursing homes also balance on another tightrope with no safety net: the possible failure of their screening processes at the door.

What if a staff member is infected outside of work and brings the condition to patients before the staff member screens positive? What do we do with our own internal patient who suddenly tests positive but has only minor symptoms? That patient may do fine, but what about the risk to the others around them? Can we justify keeping that patient when we know we would not keep the staff member?

As the current policy to isolate patients in place fails in Iowa and around the nation, our homes have come to realize that their resources will not be sufficient to prevent internal spread. With that humble assessment, our local facilities in Pottawattamie County have moved to action.

Their intention is the isolation of COVID-19 positive nursing home patients outside the facility to prevent widespread outbreak. In western Iowa, competing nursing homes have made a concerted effort to find a facility for isolation of those patients and to open that facility themselves if necessary. But no nursing home in the area has chosen to designate themselves as a COVID-19 facility and to begin transferring their current patient out of the facility.

Critical Access Hospitals could use their skilled care beds for these patients, but in western Iowa, the local health systems have a stranglehold on those relationships. They have directly asked that nursing homes not inquire about those beds. They predict the need for those as overflow from their larger urban hospitals.

Calls to the Department of Inspections and Appeals, the Iowa Department of Public Health’s nursing home division, and to local resources have been met with admiration, but no resources beyond the offer of more personal protective equipment and infection control education. With no options for the COVID-19 patient, and minimal resources directed to the nursing home problem, pressure continues to mount from the hospitals and Emergency Management.

For now, Regional Medical Coordination Centers will determine what to do when the nursing homes object to an admission. If plans are in motion to address the problem from the RMCC level, they have not been coordinated with our nursing facilities. The unknown is becoming unbearable.

This lack of inclusion is not surprising. Most nursing homes are not affiliated with the large health systems across the state, and they are used to their questions and needs being muted.

Our long-term care facilities look on at Emergency Management officials who, they fear, are not getting the full picture of the needed pandemic response. Without a voice at the table, our patients are at the mercy of a potentially misinformed authority who may demand that nursing homes agree to take contagious patients.

With no acceptable solution, our facilities carry on knowing that in the current environment, each bed they fill with a COVID-19 patient will likely fill some other patient’s cemetery plot.

This crisis will pass. Successes and failures will be debated and graded. The loss of lives that could have been saved will be included in the final evaluation. If we act now, we can still save many of those lives. The lesson is that our health is at risk when left in the hands of health system monopolies. We can learn that lesson today and make changes immediately to our system, or we can learn that in our evaluation of the aftermath of COVID-19. But it will be the lesson, either way.

Glenn Hurst, MD is a rural primary care physician in Minden, Iowa. Since completing a rural Family Practice residency at the University of Nebraska Medical Center in 2009, he has been a rural and senior health policy advocate in the state of Iowa. He is medical director at four nursing homes in Pottawattamie County.